Economic Restructuring and Governance Transformation: In-Depth Exploration

The economic and governance systems in place today are often founded on extractive models—systems that prioritize profit, power, and control at the expense of collective well-being, social equity, and ecological sustainability. These systems tend to function through top-down, hierarchical structures, where conflict is avoided, and problems are addressed with punitive, short-term solutions.

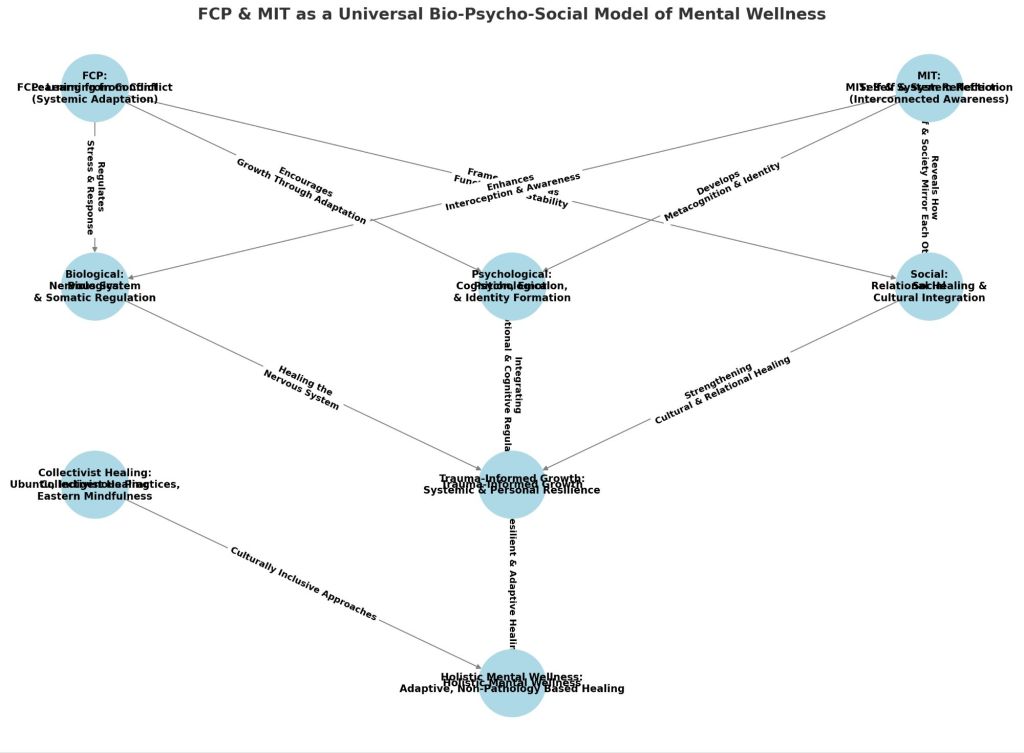

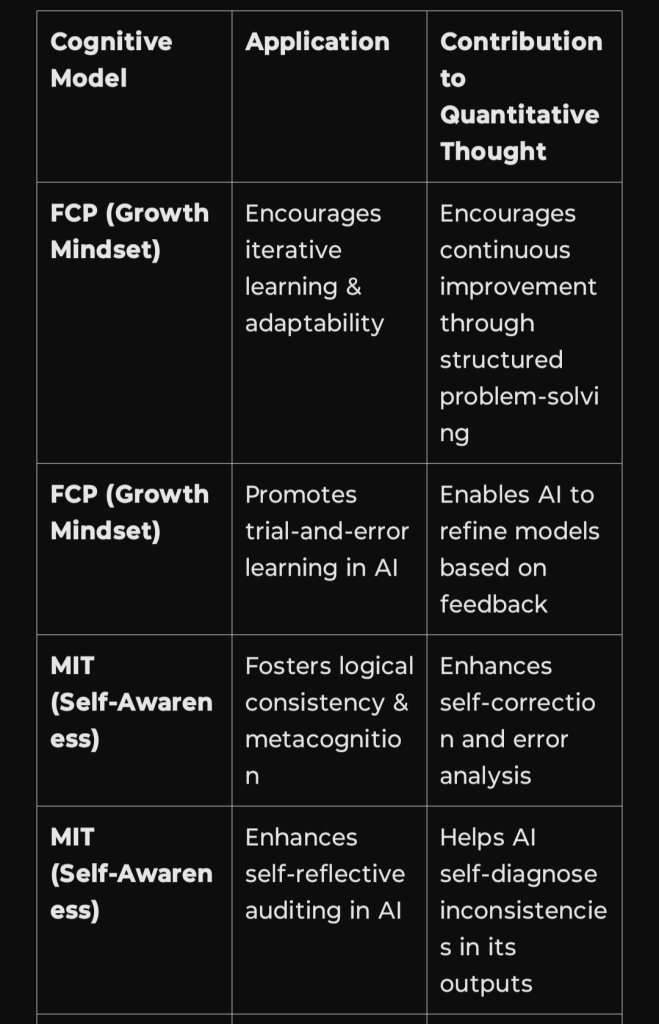

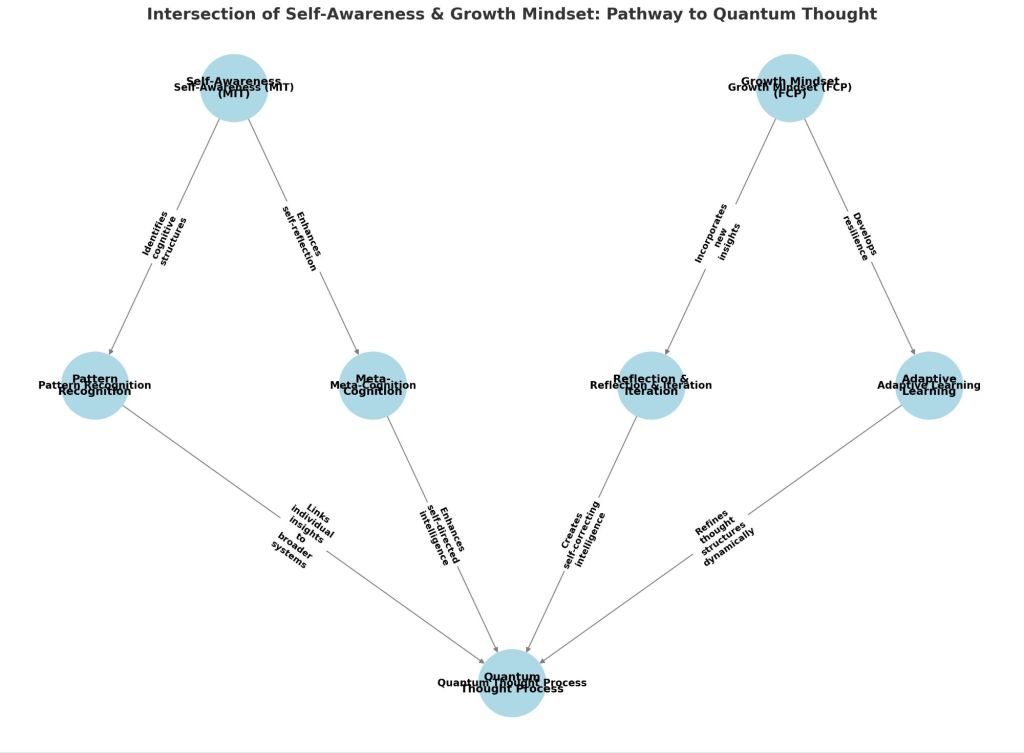

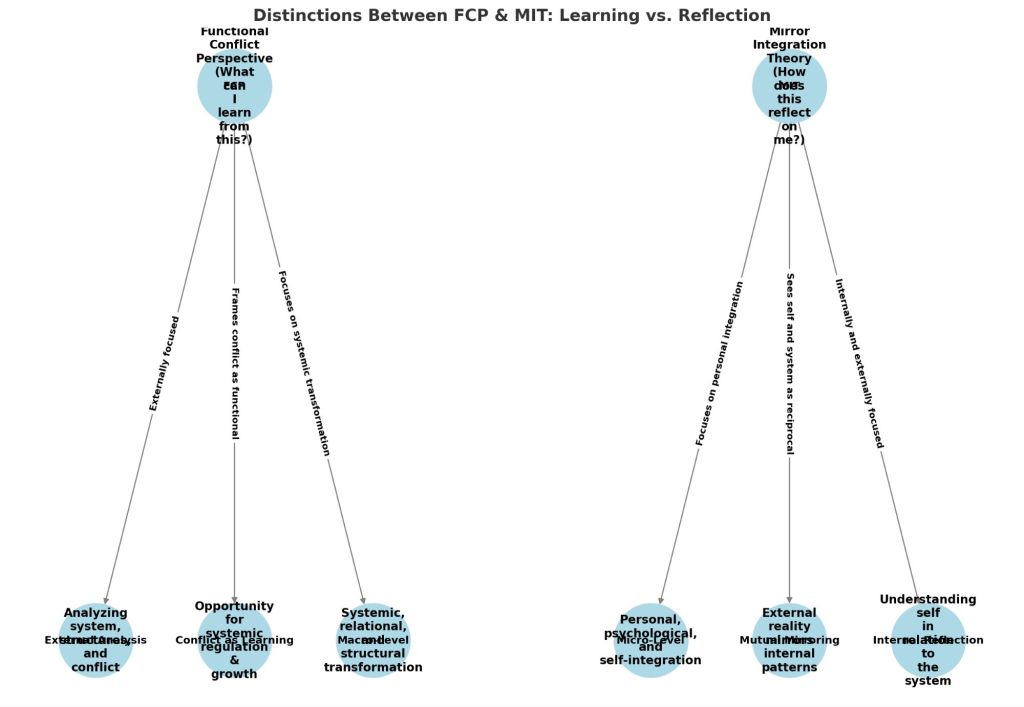

In contrast, Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) offer a transformative approach that reimagines these systems by focusing on restorative, adaptive, and regenerative structures. Below is an in-depth exploration of economic restructuring and governance transformation through the lenses of FCP and MIT.

Economic Restructuring Using FCP & MIT

Current Economic System – Extractive and Exploitative:

The traditional economic system is designed to benefit a small elite while extracting resources from the broader population. Capitalism, in its modern form, relies on market volatility, labor exploitation, and wealth extraction to generate profit. These systems have led to income inequality, social fragmentation, and environmental degradation.

Key features of traditional systems:

Wealth Extraction: The concentration of wealth in the hands of a few, driven by monopolistic practices and unchecked market forces.

Labor Exploitation: Economic structures that prioritize cheap labor, long hours, and dehumanizing work conditions, often relying on inequitable power dynamics.

Market Volatility: The booms and busts of financial systems, where market crashes disproportionately impact vulnerable populations, leading to systemic instability.

FCP-Based Economic Transformation – Regenerative Economy:

FCP-based economic restructuring offers a blueprint for moving from an exploitative system to a regenerative one, where resources are distributed more equally, and the health of communities and ecosystems is prioritized over short-term profit.

Key components of this transformation:

Cooperative Wealth Distribution: A move toward cooperative economics where the wealth created by workers is shared more equitably. This could take the form of worker-owned cooperatives, profit-sharing models, and universal basic income (UBI) to address wealth inequality.

Trauma-Informed Labor Policies: A focus on workers’ rights, dignity, and mental health, rather than viewing labor as an exploitative resource. Labor policies would prioritize work-life balance, employee empowerment, and collective decision-making.

Sustainable Economic Structures: The introduction of green economies, circular economies, and local production systems that focus on sustainability rather than endless growth. These structures are designed to align with the natural world’s processes, ensuring that economic activity restores and regenerates both ecological and social systems.

Economic Healing: The introduction of trauma-informed economics—an economic model that recognizes the psychosocial consequences of economic trauma (e.g., financial insecurity, exploitation, environmental degradation) and seeks to repair these harms through community-driven recovery and investment in mental health.

FCP in Economic Conflict Resolution:

Instead of avoiding economic conflict, FCP sees these struggles as opportunities to reframe competition and scarcity as cooperation and abundance.

Conflicts about resource distribution, environmental justice, and economic equity are addressed using restorative practices that emphasize mutual understanding, shared resources, and cooperative problem-solving.

MIT in Economic Reflection:

MIT analysis allows individuals and communities to understand how economic inequalities and systemic dysfunctions mirror personal and collective trauma.

It helps leaders and policymakers reflect on how their economic decisions affect both individual well-being and community stability.

Governance Transformation Using FCP & MIT

Current Governance Systems – Hierarchical and Punitive:

Governance systems, in their traditional forms, often operate with a top-down, coercive model that focuses on control, punishment, and exclusion. These systems tend to dehumanize individuals and marginalize communities through hierarchical power structures, where those in authority control resources, information, and decision-making.

Key features of traditional systems:

Authoritarian Governance: A system where power is concentrated at the top, and decisions are made without input or cooperation from the broader population.

Bureaucratic Freeze: Governance systems become rigid and slow to adapt, focusing on maintaining status quo rather than innovating or healing societal wounds.

Avoidance-Based Policy: Policies that ignore systemic dysfunction, creating laws and systems that suppress conflict instead of using it as an opportunity for change.

Punitive Measures: Use of criminal justice systems, law enforcement, and punishment-based policies to control rather than rehabilitate or restore societal order.

FCP-Based Governance Transformation – Restorative & Adaptive Systems:

FCP offers an alternative governance model where self-regulation, adaptability, and collective healing replace top-down control. In this system, power is distributed across levels, and decision-making is based on collaboration, conflict-resolution, and restorative justice rather than punishment.

Key components of governance transformation:

Self-Regulation and Decentralized Power: A shift from authoritarian rule to relational decision-making, where power is distributed throughout the system, allowing local communities to self-govern and adapt to their own needs.

Trauma-Informed Decision Making: Policies are designed with an awareness of the collective trauma of communities. Restorative justice, healing circles, and community-led conflict resolution are prioritized over punitive actions.

Adaptive Conflict Resolution: Conflict is reframed as a growth and learning opportunity for the system. In cases of civil unrest, FCP-based approaches would focus on healing, accountability, and repairing systemic dysfunction.

Inclusive Policy Design: Policies are created that actively include marginalized voices and focus on systemic equity, rather than exclusion or suppression.

FCP in Governance Conflict Resolution:

FCP reframes conflict in governance as a natural function that helps address systemic dysfunctions, allowing policymakers to embrace conflict and adapt systems constructively.

Instead of suppression, governance models focus on engagement, negotiation, and cooperative problem-solving.

MIT in Governance Reflection:

MIT allows society to mirror collective distress in governance structures. By recognizing how societal trauma impacts decision-making, leaders can implement policies that promote healing and restoration rather than further division and exclusion.

The mitigation of polarization in policy discussions can be achieved by understanding the unconscious biases that shape political discourse and promoting mutual understanding through collective reflection.

How These Transformations Work Together: A Synergistic Approach

The economic restructuring and governance transformation models based on FCP & MIT complement each other and work together to create a holistic societal shift:

1. Economic Systems Influence Governance Systems:

The structure of the economy determines who holds power and how resources are distributed, which affects how governance is structured and how policies are designed. By transforming economic systems into more equitable, cooperative models, governance systems can be shifted from coercion to collaboration. This creates a more stable, self-regulating society where individuals have the power to make decisions and engage with conflict productively.

2. Governance Systems Influence Economic Systems:

Governance systems dictate the policies that regulate economic activity. By applying FCP & MIT to policy-making, governments can transform economic systems to focus on well-being, equity, and sustainability rather than short-term profit. Regenerative economic models are thus supported by restorative governance that emphasizes healing, restorative justice, and systemic learning.

3. Collective Healing & Regeneration:

Both the economic and governance transformations rely on restorative practices, where conflict is seen as an opportunity for growth and healing rather than something to suppress. Self-regulation, trauma-informed decision-making, and systemic integration of FCP & MIT principles create a foundation for long-term healing, sustainability, and social harmony.

By using these transformative frameworks, we can create societal models that support restorative justice, economic equity, and adaptive governance—moving away from exploitative systems and toward systems that prioritize collective well-being, sustainability, and resilience.

How the Roadmap Works

The roadmap for both governance and economic transformation using FCP & MIT works as follows:

1. Identifying Systemic Dysfunction:

The starting point in both the governance and economic systems is to recognize existing dysfunctions, such as hierarchical power structures, wealth inequality, exploitative labor, and punitive governance.

These dysfunctions stem from unhealed societal trauma, where systems of control (e.g., authoritarian leadership, coercion, market volatility) reflect larger societal issues that need to be addressed.

2. Reframing Conflict as Growth:

Both models emphasize conflict as a learning mechanism.

FCP shifts the lens from conflict avoidance to engagement. Conflict is no longer seen as something that destabilizes the system but as an opportunity to learn, adapt, and grow.

In governance, conflict resolution becomes restorative rather than punitive. In economics, conflict over resources leads to collaboration rather than competition.

3. Adapting to Self-Regulation:

Both the economic and governance systems are transformed into adaptive, decentralized systems.

Self-regulation becomes the foundation, where systems evolve based on collective needs, instead of rigid top-down structures that perpetuate control and extraction.

Restorative practices are incorporated at every level to ensure long-term sustainability and healing.

4. Creating Regenerative Models:

The end goal of this transformation is to develop regenerative, sustainable models for both governance and the economy.

This includes redistributing wealth, cooperative labor, sustainable economic structures, and trauma-informed decision-making.

These systems, driven by self-regulation and restorative policies, replace traditional extractive models and authoritarian governance with ones that support collective healing and equity.

Impact of the Roadmap

By following this roadmap, FCP & MIT create a dynamic framework for transforming not just individual relationships and communities, but entire global systems. The process redefines how we engage with conflict at every level:

Governance: Moves away from hierarchical control to collective, self-regulated systems that prioritize emotional intelligence, collaboration, and restorative justice.

Economics: Transitions from wealth extraction and exploitation to cooperative, regenerative economic models that focus on sustainability and human well-being.

These transformations represent a holistic, integrated approach to systemic change, driven by adaptive conflict resolution and mutual healing.

Description of the Visual Flowcharts and the Roadmap:

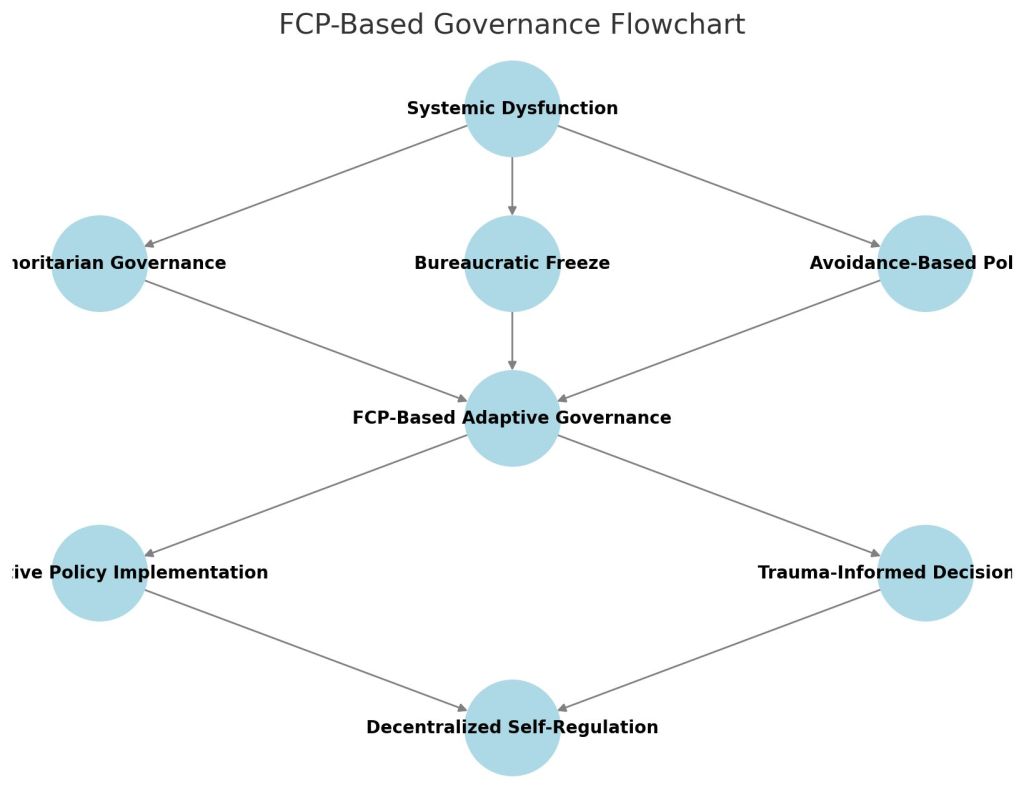

The FCP-Based Governance Flowchart illustrates the transition from traditional, hierarchical governance structures to self-regulating, trauma-informed models:

Starting Point: Systemic Dysfunction

The flowchart begins with Systemic Dysfunction, which is commonly seen in authoritarian governance, bureaucratic freeze, and avoidance-based policy.

These systemic issues are rooted in conflict avoidance or top-down control mechanisms, often reflecting societal trauma (e.g., power imbalances, exclusion, repression).

Shift to FCP-Based Adaptive Governance

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) is introduced as a means to reframe conflict not as something to suppress but as a learning and growth mechanism.

Conflict is no longer seen as something that destabilizes the system, but rather as an opportunity for systemic healing.

Through adaptive leadership, conflict becomes an opportunity for engagement and learning, leading to a more resilient and self-regulating system.

Key Components of FCP-Based Governance

Trauma-Informed Decision-Making: Policy-making and leadership are rooted in restorative practices that promote collective healing.

Restorative Policy Implementation replaces punitive measures and encourages community-led conflict resolution, collaborative problem-solving, and self-regulation.

Final Stage: Decentralized Self-Regulation

The system becomes non-hierarchical, with power distributed across local, relational systems.

Governance becomes adaptive and responsive, driven by the collective’s needs and not by rigid, top-down mandates.

This flowchart shows how conflict within governance can be redefined, resulting in an adaptive and restorative leadership model that is more sustainable, flexible, and grounded in emotional intelligence.

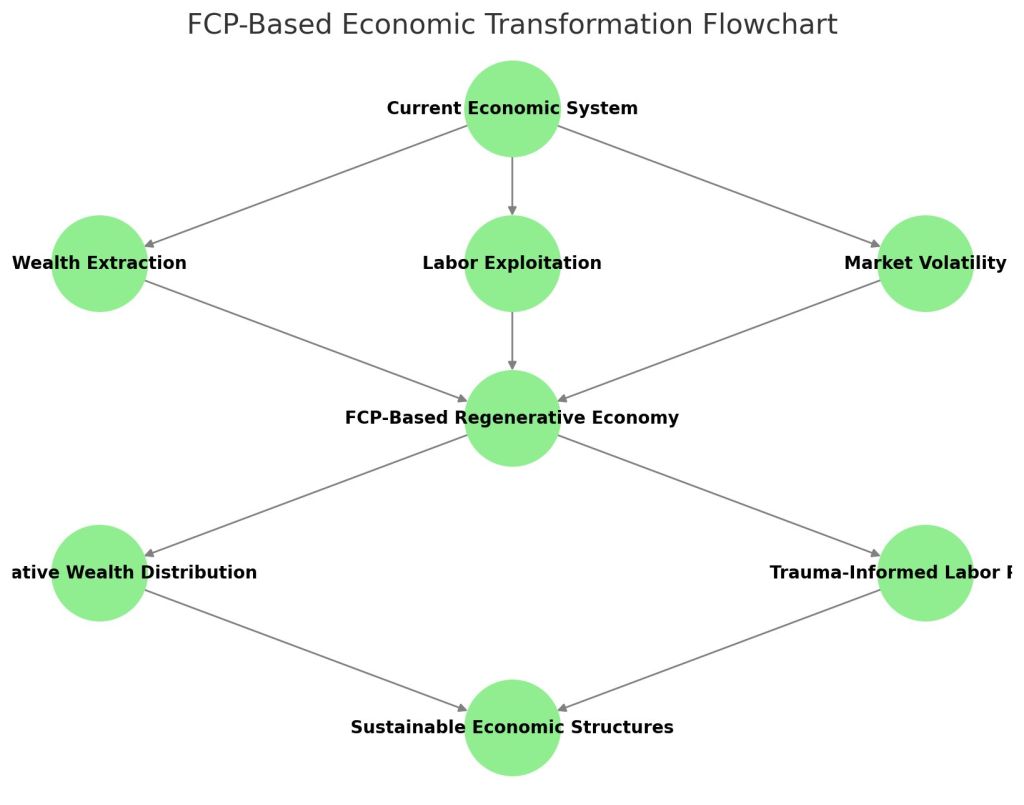

The FCP-Based Economic Transformation Flowchart focuses on how economic systems can evolve from extractive, exploitative models to regenerative, sustainable economies that prioritize human well-being and systemic healing:

Starting Point: Current Economic System

The current economic system is shown as extractive, emphasizing wealth concentration, labor exploitation, and market volatility.

These systems create social inequality, where the wealthiest few benefit at the expense of the broader population. These systems mirror trauma responses, such as scarcity, inequity, and survival mentality.

Shift to FCP-Based Regenerative Economy

FCP-based economic models aim to shift from exploitation to more collaborative, equitable systems. By using conflict as a learning opportunity, these models encourage a reimagining of how wealth and resources are distributed.

This transformation encourages sustainable systems where resources are used not just for short-term profit, but for long-term collective well-being.

Key Components of FCP-Based Economy

Cooperative Wealth Distribution: Wealth is not hoarded by a few but shared through cooperative structures, where collective well-being and equity are prioritized.

Trauma-Informed Labor Policies: Economic policies embrace inclusivity, respect workers’ dignity, and provide sustainable livelihoods, replacing exploitative models with more nurturing labor environments.

Final Stage: Sustainable Economic Structures

The flowchart ends with the goal of regenerative, sustainable economic systems that prioritize human connection, ecological health, and economic equity.

Instead of wealth extraction, the system focuses on cooperation and restorative practices, leading to more resilient communities and equitable economies.

The two flowcharts visualize the systemic transformation that Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) can facilitate in both governance and economic systems. These diagrams serve as roadmaps to shift from punitive, coercive systems to trauma-informed, restorative, and adaptive systems in leadership, governance, and economic structures.

Case Studies: Real-World Examples of Economic Restructuring and Governance Transformation

1. Case Study: Worker-Owned Cooperatives (Economic Restructuring)

Background: In traditional capitalist economies, businesses are typically owned by a small group of shareholders or a single owner, and profits are distributed among the owners rather than the workers. This creates wealth inequality, where the people who contribute most to the company’s success (the workers) are often the least rewarded. In contrast, worker-owned cooperatives are businesses that are owned and run by the people who work there, and the profits are shared among them.

FCP-Based Transformation:

Conflict as Learning Mechanism: Worker-owned cooperatives create an environment where conflicts between owners (workers) are seen as opportunities to address systemic issues in the business. FCP reframes disputes as opportunities for team growth, problem-solving, and shared learning. This creates a collaborative environment where workers’ voices are valued, and the organization can learn from its struggles.

MIT Reflection: Workers and leaders engage in self-system mirroring, regularly reflecting on how their workplace conflicts reflect broader systemic dysfunctions, such as economic inequality or labor exploitation. Through MIT, workers begin to recognize that the business’s challenges are not inherent failures but symptoms of systemic issues that can be addressed by changing how they engage with their roles and each other.

Outcome:

Cooperative Wealth Distribution: Workers share profits, and decision-making is democratic, allowing for more equitable wealth distribution and empowerment.

Sustainability & Resilience: These businesses tend to be more resilient and stable because they are not reliant on outside investors, and the workers have a vested interest in the long-term health of the company. The businesses are able to maintain high levels of employee engagement and satisfaction, reducing turnover and building a healthy organizational culture.

Example:

Mondragon Corporation: A large federation of worker cooperatives based in Spain, where more than 80,000 workers own and manage businesses in various industries, including finance, retail, and manufacturing. This model has contributed to economic stability and sustainable growth, providing jobs, healthcare, and housing for its workers.

2. Case Study: Restorative Justice in Criminal Justice Reform (Governance Transformation)

Background: Traditional criminal justice systems focus on punitive measures such as imprisonment, fines, and other forms of retribution. This often leads to recidivism, where individuals re-offend after serving their sentence, and fails to address the root causes of crime (e.g., poverty, mental illness, trauma).

FCP-Based Transformation:

Conflict as Learning Mechanism: Restorative justice processes use FCP’s approach by involving victims and offenders in dialogue, allowing them to engage in conflict learning. Instead of viewing the criminal act as simply a law violation, restorative justice focuses on how to repair the damage caused to the victim, the community, and the offender. It is trauma-informed, recognizing that victims and offenders alike may carry deep emotional wounds.

MIT Reflection: Both offenders and victims engage in self-reflection and mirroring to explore how societal conditions, such as poverty, discrimination, or childhood trauma, have shaped their behavior. For example, offenders may realize how their actions mirror societal dysfunctions, such as economic inequality or lack of mental health support.

Outcome:

Restorative Practices: Offenders are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions in a healing context, where their behavior is understood in light of broader societal dynamics.

Community-Based Healing: By fostering empathy between offenders and victims, restorative justice systems build community relationships and encourage social reintegration rather than stigmatization.

Example:

New Zealand’s Family Group Conferences: A program in New Zealand where offenders, victims, and their families come together to discuss the crime and decide on appropriate restorative actions. These conferences have led to a reduction in reoffending rates and are considered an effective alternative to incarceration.

3. Case Study: Participatory Budgeting (Governance & Economic Restructuring)

Background: In traditional governance systems, budget decisions are typically made by elected officials or centralized power structures without direct input from the citizens or communities affected by those decisions. This can lead to misallocation of resources, especially in marginalized communities.

FCP-Based Transformation:

Conflict as Learning Mechanism: Participatory budgeting allows communities to engage in decision-making, identify needs, and prioritize resources collectively. The process allows citizens to discuss economic challenges, gaps in public services, and local issues to learn from each other about systemic inequalities that may not have been previously addressed by the government.

MIT Reflection: Citizens engage in self-system reflection, recognizing how the lack of resources or systemic neglect in their communities mirrors larger governmental dysfunctions. By discussing how these issues affect their daily lives, they build awareness of the systemic factors contributing to their struggles.

Outcome:

Cooperative Wealth Distribution: Participatory budgeting leads to more equitable allocation of public funds, ensuring that marginalized communities receive necessary resources.

Local Empowerment: Citizens gain more control over how public funds are spent, which builds a sense of ownership and responsibility for community improvement.

Example:

Porto Alegre, Brazil: This city implemented participatory budgeting in the 1990s, allowing citizens to directly decide on how a portion of the city’s budget is spent. The program led to improved public services, greater equity in spending, and increased political engagement among citizens, particularly in low-income neighborhoods.

Conclusion: The Synergy Between Economic and Governance Transformation

These case studies show the real-world applicability of FCP & MIT in economic restructuring and governance transformation. The key to their success is recognizing that conflict and dysfunction in economics and governance are not obstacles to be avoided but opportunities for systemic learning and growth.

By reframing conflict as a learning mechanism, self-awareness through MIT, and applying FCP’s functional approach to system-wide change, societies can move toward more equitable, sustainable, and resilient systems. These transformations decentralize power, empower marginalized communities, and create regenerative economic and governance models that prioritize collective well-being and healing.

The integration of these approaches provides a holistic roadmap for creating a just, adaptive, and trauma-informed society.