For too long, psychology has framed neurodivergence as a deviation from an unexamined, supposedly objective standard of neurotypicality. But what if the framework itself is flawed? What if neurotypicality is not a neutral default but a socially conditioned state that reflects hierarchical norms, binary thinking, and emotional suppression rather than natural cognitive function? Instead of defining neurodivergence as a disorder, I propose turning the tables on pathology and constructing a reverse-engineered DSM definition of neurotypicality—one that reflects its true characteristics as a learned, not inherent, cognitive state.

If I were to diagnose neurotypicality, I would define it as a condition marked by binary thinking, rigid adherence to social hierarchies, suppression of emotional and sensory awareness to conform to external expectations, and reliance on authority rather than internal intuition to determine truth. This framework does not emerge from biological necessity but from social conditioning that forces individuals into hierarchical roles that prioritize obedience, productivity, and detachment over relational intelligence and holistic cognition. In contrast, neurodivergence is not a single state but an umbrella encompassing any way of thinking that does not conform to this binary framework—embracing complexity, fluidity, and interdependent ways of processing the world.

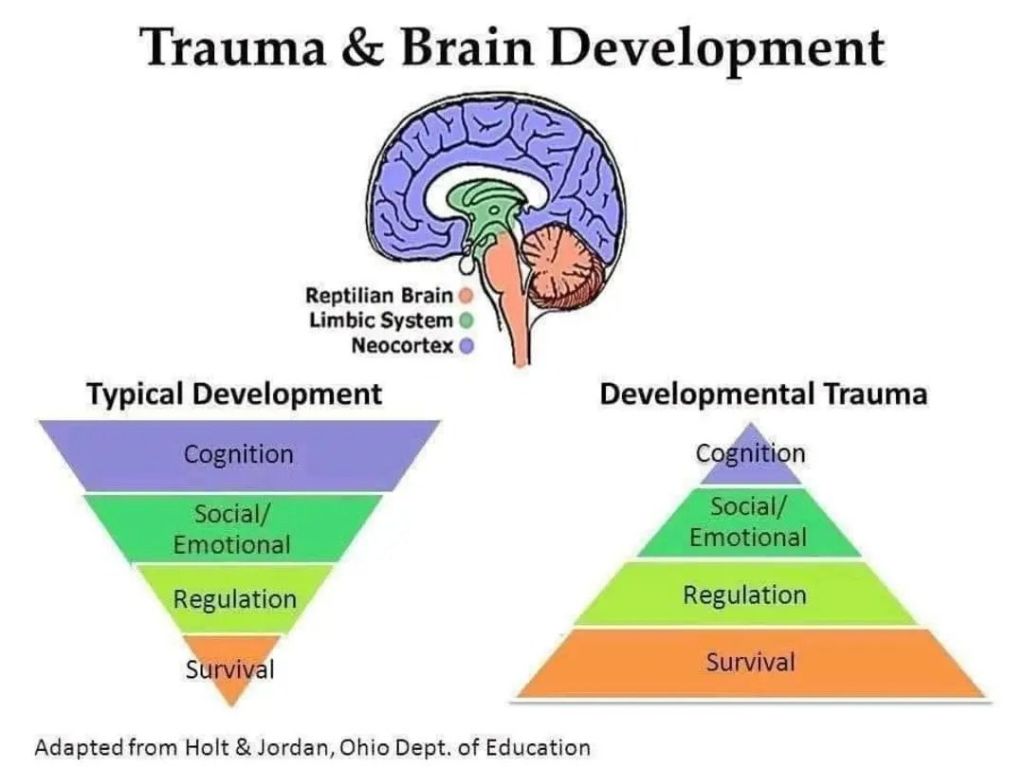

This reframing aligns with what neuroscience tells us about brain development under trauma versus typical development. In a stable environment, human cognition follows a natural progression: basic survival needs are met first, allowing for emotional regulation, then social and emotional skills, and finally higher cognitive abilities like problem-solving and deep empathy. However, in trauma conditions, this development is disrupted—the brain remains in survival mode, limiting access to emotional and social intelligence, and reinforcing black-and-white thinking as a defense mechanism. I argue that hierarchical socialization mimics this trauma response, forcing people into a survival-based framework where dominance, compliance, and selective empathy replace natural relational cognition.

This is evident in childism, adultism, and ableism, which systemically devalue those who exist outside the rigid norms of neurotypicality. Children, disabled people, and the elderly—groups that naturally function in relational, interdependent ways—are treated as burdens, their cognition labeled as deficient because it does not conform to a system that rewards detachment and self-suppression. In reality, these groups often embody the unconditioned human state—one that values connection, sensory integration, and emotional authenticity over hierarchical compliance. Their marginalization is not a reflection of their inability to function but rather a symptom of a system pathologically invested in suppressing human interdependence.

This is why selective empathy is a feature, not a flaw, of neurotypicality. In hierarchical systems, those at the top expect understanding and deference, while those at the bottom are denied the same courtesy. This mirrors the Double Empathy Problem, in which dominant groups assume their way of thinking is the default and place the burden of understanding on marginalized groups while excusing their own lack of reciprocity. It is not the oppressed who lack empathy—it is the system itself that suppresses it through trauma-based conditioning. Those who ridicule deep empathy and emotional intelligence as “childish” or “irrational” are not demonstrating superior cognitive function; rather, they are displaying the defensive mechanisms of a system that mistakes emotional detachment for maturity and domination for intelligence.

To move forward, we all must reject the inherited pathology model and redefine neurotypicality for what it is—a trauma-driven, hierarchy-enforcing cognitive framework that has been falsely labeled as the default. Just as individuals can heal from trauma by reconnecting to their relational intelligence, societies can heal by dismantling hierarchical conditioning and rebuilding systems around mutual care and interdependence. When Jesus said, “Unless you become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven,” he was not advocating for naivety but for a radical return to a state of relational openness, emotional presence, and rejection of coercive power structures. The future of human progress lies not in further reinforcing neurotypicality as an unquestioned norm, but in turning the tables on pathology and reclaiming the full spectrum of human cognition as valid, adaptive, and worthy of recognition.

1. Trauma and the Loss of Relational, Non-Coercive Ways of Being

The left side of the image (Typical Development) shows a stable, hierarchical progression where survival needs are met first, allowing for emotional regulation, social-emotional skills, and higher cognitive functions (such as empathy, problem-solving, and abstract reasoning) to develop naturally.

The right side (Developmental Trauma) shows how trauma disrupts this natural sequence, forcing the brain to prioritize survival mechanisms (fight, flight, freeze, fawn), which in turn impairs regulation, social connection, and cognitive growth.

In hierarchical societies that devalue relational connection and force children into emotionally coercive environments (rigid discipline, neglect, or emotionally dismissive caregiving), the nervous system remains in survival mode, preventing full emotional and intellectual development.

2. Hierarchical Socialization Mimics Developmental Trauma

Just as trauma traps the brain in a survival-first mode, hierarchical systems trap people in dominance-first or compliance-first conditioning rather than fostering relational, cooperative ways of being.

Childism: Many children in coercive family and school structures experience chronic stress or low-level trauma, constantly navigating power imbalances instead of secure attachment and mutual respect. This can leave them emotionally dysregulated and more vulnerable to authoritarian conditioning.

Adultism & Ableism: Societal structures reinforce the idea that those who are “weaker” (children, disabled people, the elderly) are less valuable because they require relational support—mirroring how traumatized individuals are often dismissed for being “too emotional” or “irrational.”

3. The Empathy Suppression Loop

In hierarchical societies, those stuck in survival mode develop coping strategies that reinforce hierarchy rather than relational connection:

Avoidant/Dismissive Responses → “People need to toughen up” (emotional detachment as a defense mechanism).

Fawning/Submission Responses → “If I comply, I will be safe” (Wendy Syndrome).

Power-Seeking Responses → “I need to dominate others to protect myself” (Peter Pan Syndrome, emotional avoidance).

This leads to a society where higher cognitive and relational functions are suppressed, and people are conditioned to prioritize survival strategies that reinforce hierarchical control rather than mutual care.

4. Healing Requires Breaking the Trauma-Hierarchy Cycle

Just as developmental trauma can be healed through safety, regulation, and relational security, societal structures must also shift from hierarchical dominance to relational, trauma-informed governance.

Becoming like little children, as Jesus suggested, means returning to a state where emotional security allows for natural empathy, cooperation, and higher cognition to flourish.

This means undoing coercive socialization, recognizing the impact of trauma on empathy suppression, and building systems that foster relational well-being rather than dominance and compliance.

This image directly supports the argument that hierarchical conditioning mimics trauma by keeping individuals in survival-based ways of relating rather than relational, cooperative, and cognitively expansive states. If we want to build a more empathetic and just society, we must prioritize healing at both the individual and structural levels, breaking the cycle of trauma-driven social organization and restoring the conditions that allow full human development.

Hierarchies, Selective Empathy, and the Double Empathy Problem

Empathy is sometimes considered a childlike trait because it is associated with openness, emotional sensitivity, and an unfiltered connection to others’ feelings—qualities that children often exhibit before they learn social defenses, hierarchical thinking, or cultural conditioning that suppresses emotional expression. However, this framing is misleading because empathy is actually a sophisticated social and cognitive skill that deepens with maturity, rather than something inherently naïve or childish.

Yet, as individuals are socialized into hierarchical systems, empathy often becomes selective—reserved for those within one’s in-group or those in higher social positions while being suppressed toward those in lower-status positions. Hierarchies teach people to direct care and understanding toward authority figures and peers while justifying detachment or even cruelty toward those perceived as less powerful. This selective distribution of empathy becomes a structural feature of social systems, where those at the top expect to be understood while those at the bottom are left to navigate their emotions without reciprocal recognition.

This dynamic mirrors the Double Empathy Problem, originally conceptualized to explain the disconnect between neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals. In hierarchical societies, the dominant group assumes its way of thinking, feeling, and communicating is the default, placing the burden of understanding entirely on the marginalized group. Just as neurodivergent individuals are expected to navigate neurotypical social norms while their own experiences are ignored or invalidated, those in lower hierarchical positions—whether due to class, race, gender, or disability—are expected to empathize with those in power while receiving little understanding in return. This is not a failure of empathy in marginalized groups but a systemic failure of reciprocity imposed by the structure of power itself.

Hierarchies do not eliminate empathy, but they distort its distribution, creating an asymmetry where dominant groups demand understanding while dismissing the emotional realities of those beneath them. This selective application of empathy is what allows structural oppression, economic inequality, and social exclusion to persist—because those in power can justify the suffering of others while maintaining an internal narrative of moral righteousness. In this way, the Double Empathy Problem extends beyond neurodivergence to all forms of systemic marginalization, making it clear that the real issue is not a lack of empathy but a socially conditioned refusal to extend it equally. Overcoming this requires breaking hierarchical conditioning and reclaiming empathy as a mutual, relational process rather than a tool of social control.

A lack of empathy is not a sign of strength or intelligence but rather a symptom of emotional damage, disconnection, and stunted psychological growth. Empathy is fundamental to emotional intelligence, moral reasoning, and social cohesion, yet in hierarchical cultures that reward dominance over connection, its suppression is often framed as a virtue. People who mock or look down on empathetic individuals are not displaying maturity but rather a socially conditioned form of emotional immaturity—one that equates detachment with power and vulnerability with weakness. This phenomenon is deeply tied to Peter Pan Syndrome and Wendy Syndrome, both of which emerge from dysfunctional emotional development shaped by hierarchical conditioning.

Peter Pan Syndrome, characterized by emotional avoidance and an inability to take on mature responsibilities, is deeply rooted in hierarchical systems that suppress emotional depth in favor of superficial power dynamics. Those affected often dismiss or ridicule empathy because they see emotional engagement as a threat to their carefully maintained detachment. They have been conditioned to believe that to feel deeply is to be weak, and so they construct an identity around emotional aloofness, cynicism, or avoidance—often positioning themselves as rebels against perceived “childish” emotionality when, in reality, their avoidance is the immature response. This reflects the way hierarchical systems distort emotional development: those at the top of social structures, or those who aspire to be, are rewarded for strategic detachment rather than relational depth.

On the other hand, Wendy Syndrome, which manifests in excessive caretaking and self-sacrificial behavior, arises from the same system but on the opposite end. Those conditioned into Wendy Syndrome are socialized to overextend empathy in order to maintain relationships with emotionally stunted individuals, often suppressing their own needs in the process. This dynamic is especially visible in gendered hierarchies, where women and feminine-coded individuals are expected to bear the emotional burdens of others—providing care, understanding, and emotional labor without receiving the same in return. Hierarchical societies need Wendys to sustain the illusion that Peter Pans are functioning adults; they need people who will bridge the empathy gap, making up for the emotional immaturity that hierarchical conditioning creates.

The ridicule of empathy, then, is not about intelligence or pragmatism—it is a defensive mechanism designed to justify emotional underdevelopment. People who mock empathy are often unconsciously protecting themselves from the discomfort of realizing how emotionally stunted they are. Hierarchical cultures produce emotionally fragile individuals, not resilient ones—people who cannot navigate deep relationships, struggle with collective problem-solving, and rely on avoidance rather than true connection. True maturity is not the suppression of empathy but the ability to integrate it wisely—to feel deeply without being overwhelmed, to care without self-erasure, and to recognize that emotional intelligence is not a liability but one of the greatest markers of human strength.

When viewed through this lens, Peter Pan Syndrome and Wendy Syndrome are not just individual pathologies but manifestations of a broader social dysfunction—one that discourages emotional depth, fosters selective empathy, and ultimately weakens human relationships at every level. Healing from this conditioning requires breaking free from hierarchical distortions of maturity, reclaiming empathy as a strength, and fostering a society that values emotional intelligence not as an exception but as the norm.

Relational, non-coercive ways of being are the natural state of children before they are conditioned by power structures. When Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3), he was referring to a mindset that rejects social hierarchies, ego-driven status, and power-seeking behaviors—aligning with the idea that children embody a natural state of openness, humility, and unfiltered empathy before hierarchical conditioning distorts these qualities.

1. Children as a Model of Non-Hierarchical Thinking

Children naturally engage in egalitarian relationships because they have not yet been conditioned to see the world through rigid social hierarchies. They relate to others based on immediacy, emotional connection, and reciprocity, rather than status, wealth, or power.

Jesus’ teachings frequently challenge social hierarchies—whether it’s rebuking the powerful, uplifting the poor, or warning against seeking status (e.g., “The greatest among you will be your servant” – Matthew 23:11). This aligns with children’s innate lack of concern for hierarchical positioning.

2. The Kingdom of Heaven as a Rejection of Worldly Status

Many of Jesus’ parables flip hierarchical values upside down: the last shall be first, the meek shall inherit the earth, the humble will be exalted (Matthew 5:5, Matthew 20:16).

In this context, “becoming like children” could mean unlearning the hierarchical conditioning of adulthood—letting go of the competitive, power-driven mindset that governs worldly institutions.

Just as children do not judge people based on wealth or status, entering the kingdom of heaven requires returning to a state where human worth is not measured by hierarchical rank but by relational and spiritual integrity.

3. Empathy, Vulnerability, and Trust

Children embody emotional openness, vulnerability, and an unfiltered willingness to trust and connect—qualities that are often stripped away by hierarchical socialization.

Hierarchies demand emotional suppression and selective empathy, whereas children’s interactions are driven by authentic relational attunement.

Jesus often taught through relational ethics rather than legalistic hierarchy—suggesting that the “kingdom of heaven” is built on love, mutual care, and non-coercive relationships, much like how children form bonds.

4. The Rejection of Power-Seeking Behavior

Right before Jesus makes this statement in Matthew 18, the disciples ask “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” (Matthew 18:1), implying that they are still thinking in terms of power and hierarchy.

Jesus responds by placing a child among them, symbolically demonstrating that greatness in God’s vision is not about dominance but about humility and relational purity.

This mirrors his consistent rejection of social stratification, such as when he says, “Whoever wants to be first must be last” (Mark 9:35).

The Call to Unlearn Hierarchical Thinking

By telling people to become like children, Jesus was urging them to return to a state of humility, relational integrity, and non-hierarchical social engagement. Rather than reinforcing a top-down system where power and dominance determine worth, he envisioned a reality where mutual care, empathy, and humility define human relationships—a direct challenge to the rigid hierarchies of both his time and ours.

Our society’s ableism, childism, and adultism are deeply rooted in the way hierarchical power structures condition people away from relational, non-coercive ways of being and into systems of control, dominance, and stratification. Children, disabled people, and the elderly (as well as other marginalized groups) often exist in a more relational, interdependent state, which directly contradicts the hierarchy-driven values of individualism, competition, and productivity that dominate modern society. Because of this, they are devalued, dismissed, and treated as burdens rather than as equal, autonomous beings.

1. Childism: The Systemic Oppression of Children

Children naturally operate outside of rigid social hierarchies, forming relationships based on emotional connection rather than status, wealth, or authority. However, as they grow, they are conditioned into obedience-based systems where adults exert control over their autonomy, emotions, and even bodily integrity.

Children’s dependence on adults is pathologized rather than honored, leading to widespread acceptance of coercive discipline rather than collaborative caregiving.

Their emotions and needs are frequently dismissed as “immature” or “irrational,” reinforcing the idea that hierarchical power is justified by intelligence or emotional suppression.

The infantilization of children (treating them as incapable of rational thought) coexists with unrealistic expectations of emotional self-regulation, forcing them into premature independence rather than allowing for natural interdependence.

This conditioning normalizes power imbalances, teaching people that those in lower-status positions (whether due to age, disability, or social class) deserve less autonomy and respect—which later manifests in adultist and ableist structures.

2. Adultism: The Worship of Productivity and Control

Adultism is the belief that adults (particularly able-bodied, working-age adults) are superior to children and the elderly, which stems from capitalist and hierarchical values that equate worth with economic productivity and emotional detachment. In an adultist society:

Emotional expression is suppressed because rationality, detachment, and self-sufficiency are considered more “mature” than relational ways of being.

The natural human need for care, rest, and interdependence is devalued, leading to a society that prioritizes extraction over well-being.

Older adults and disabled individuals are treated as less valuable because they do not contribute to the economy in the same way as working-age adults.

Adultism reinforces ableism by pathologizing any state of dependence and conditioning people to see reliance on others as shameful rather than natural.

3. Ableism: The Devaluation of Interdependence

Ableism functions within the same hierarchical framework, where bodies and minds that do not conform to capitalist productivity standards are considered inferior. Just as children are devalued for their dependence, disabled people are often denied autonomy and agency because they exist outside of society’s rigid definitions of “independence.”

The modern world is built for high-efficiency, high-output individuals, disregarding the fact that many human beings function in ways that are more cyclical, sensory-driven, or interdependent.

Just as children are expected to self-regulate beyond their developmental capacity, disabled people are often expected to conform to neurotypical and able-bodied standards rather than having society adapt to their needs.

Care work is undervalued, even though all human beings—disabled or not—require care at different points in life. The rejection of care is directly tied to adultist and ableist conditioning.

How Hierarchical Conditioning Creates These Systems

At its core, childism, adultism, and ableism all serve the same function: maintaining a rigid hierarchy where dependence, relationality, and non-coercive ways of being are suppressed in favor of power, control, and productivity. The natural, unfiltered empathy of children must be conditioned out of them for hierarchical systems to function, because a society built on empathy and interdependence would reject coercive authority outright.

This is why children, disabled people, and the elderly are devalued—they embody the very things hierarchical societies seek to erase: relational living, emotional openness, and interdependence. When Jesus said, “Become like little children to enter the kingdom of heaven,” he was advocating for a return to these lost qualities—a rejection of coercion, dominance, and selective empathy. To dismantle ableism, childism, and adultism, we must undo the conditioning that strips us of our innate capacity for relational, mutual care and embrace a world that values people not for what they produce, but for who they are.