Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM)

1. Introduction: Acknowledgment of Critique and Evolution of the Framework

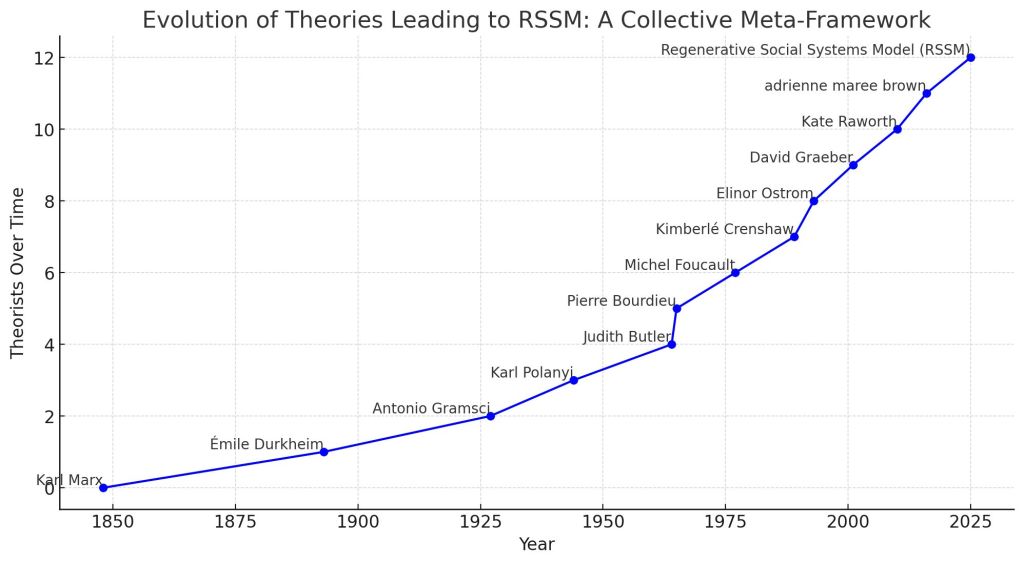

We would like to begin by thanking the colleague who provided a thoughtful critique of the initial Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) framework. This critique was invaluable in highlighting several shortcomings and opportunities for growth. It pointed out a lack of depth in our original approach and the limitations of relying too heavily on classical theories without updating or enriching them. The feedback also noted our failure to integrate the concept of power in a way that recognizes power as both structured (institutionalized and systemic) and dynamic (circulating through discourse and daily practices). Additionally, it was observed that the original framework remained constrained by academic silos – it drew narrowly from certain disciplines and neglected insights from others, resulting in an incomplete picture.

These critiques prompted a deep re-examination and restructuring of our framework from the ground up. In response, we embarked on an extensive interdisciplinary integration, drawing from a much wider range of theoretical perspectives. The result of this transformative process is the Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM), a meta-framework that addresses the earlier gaps. RSSM represents a significant evolution beyond the FCP, incorporating richer depth of analysis, bridging formerly isolated academic domains, and reconceptualizing key concepts like power, identity, and change. What follows is a presentation of RSSM, its core principles, the changes made from the original framework, the breadth of theorists now integrated, and an explanation of why this new name and approach better capture the aims of the framework.

2. The Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM): A Meta-Framework for Systemic Transformation

Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM) is proposed as a relational, regenerative, and emergent systems model for understanding and guiding systemic transformation. It is relational in that it focuses on the interconnections and relationships between various social domains (governance, economy, identity, justice, ecology) rather than treating them in isolation. It is regenerative in emphasizing processes that renew, heal, and adapt within social systems, drawing inspiration from how living systems sustain themselves through cycles of growth and restoration. It is emergent in recognizing that complex social change arises from iterative, recursive interactions over time, rather than from any single linear cause or one-time upheaval. As a meta-framework, RSSM does not belong solely to one academic field or ideology; instead, it serves as an integrative model that can be applied across disciplines to inform transformative practice.

At its heart, RSSM is built on several core principles that encapsulate this relational and regenerative ethos. These principles outline how different aspects of society can be reconceived in line with regenerative systems thinking:

- Governance as Regenerative Cycles – Governance structures are viewed as adaptive and participatory cycles of power, rather than fixed top-down hierarchies. This principle implies that decision-making and power distribution should function like a renewable cycle: inclusive feedback loops that allow continual learning, adjustment, and sharing of power. Authority is not held permanently by a single actor or institution; instead, power is circulated and co-created with community participation. This approach is informed by ideas such as participatory democracy and cybernetic feedback in governance, ensuring that policies and institutions can evolve in response to the needs of the people and the environment. By conceptualizing governance as a regenerative process, RSSM embraces Michel Foucault’s notion of power as ubiquitous and diffuse (operating through daily practices and knowledge) alongside Antonio Gramsci’s emphasis on structured power dynamics and hegemony. In practice, this could mean governance systems that routinely incorporate community deliberation, periodic power redistribution or term limits, and conflict resolution mechanisms that rejuvenate rather than merely suppress dissent. The result is a political system capable of self-correction and growth, much like an ecosystem that regenerates after disturbance.

- Economy as a Living System – RSSM reconceives the economy not as a zero-sum competitive arena, but as a living, circulating system of wealth and resources. In this view, wealth is a renewable resource that gains value through continuous circulation and equitable distribution, rather than through extraction and hoarding. An economy should function analogously to an ecosystem, where nutrients (resources, capital, knowledge) cycle through communities, fostering mutual abundance without degrading the source. This principle draws on Karl Polanyi’s idea of re-embedding the economy within social relations and the natural environment, as well as on feminist and ecological economics that emphasize care, cooperation, and sustainability (for example, Silvia Federici’s work on the commons and social reproduction, or Vandana Shiva’s advocacy of biodiversity and local knowledge in economics). It also aligns with Immanuel Wallerstein’s and Andre Gunder Frank’s world-systems perspective by being mindful of how global inequalities are structurally created, and seeks to transform those by fostering regenerative economic relationships. In practical terms, treating the economy as a living system could involve promoting circular economies (where materials and goods are reused and recycled), cooperative business models, community wealth building, and measures of prosperity that account for well-being and ecological health rather than only profit. By seeing economy as alive and evolving, RSSM moves away from the mechanistic, extractive logic of classical capitalism toward a vision of economics rooted in reciprocity, resilience, and shared prosperity.

- Identity as a Dynamic Process – In RSSM, social identities (such as class, race, gender, nationality, etc.) are understood as dynamic, intersectional, and relational processes rather than fixed categories or essences. This means an individual’s identity is continually shaped and reshaped through interactions, experiences, and relationships, and through structures of society – much as an organism adapts within an ecosystem. We embrace an intersectional perspective: people inhabit multiple social positions simultaneously, and these intersecting positions jointly influence one’s experiences and opportunities. For example, the way one experiences power or injustice is affected not just by class or just by gender, but by the interaction of class and gender and race, and so forth. This principle is heavily informed by contemporary social theory: it integrates insights from Judith Butler’s concept of gender performativity (the idea that gender is continuously created through performance and discourse), Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality (though not listed among the theorists, her influence underpins the term intersectional), and Dorothy Smith’s standpoint theory which highlights that knowledge is situated in one’s social position. It also draws from post-structuralists like Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, who see identity as a process of becoming rather than a stable being. By treating identity as fluid and relational, RSSM avoids simplistic binary classifications (e.g., oppressor vs. oppressed, or male vs. female) and instead encourages an analysis of how identities are co-constructed and how power circulates through these social relations. In application, this could mean that policies and social programs acknowledge diverse identities and are tailored to the complex realities of people’s lives, rather than assuming one-size-fits-all categories. It also means that movements for social change must remain attentive to inclusivity, ensuring that the voices of those at the intersections of multiple marginalized identities are centered.

- Justice as Structural Healing – RSSM approaches justice not merely as punishment for wrongdoing or a balancing of scales, but as a process of healing social and structural wounds. This principle views social conflict and injustice as symptoms of deeper structural problems and historical traumas that need to be addressed and healed. Rather than casting conflict or deviance only as disruptions to be suppressed or punished (as a strictly functional perspective might), RSSM sees conflict as potentially generative – an opportunity to surface grievances, acknowledge harms, and transform the underlying conditions that gave rise to them. This is aligned with the ethos of restorative justice and transformative justice frameworks. Influenced by scholars and activists like Howard Zehr (who pioneered restorative justice), Angela Davis and Mariame Kaba (who advocate for prison abolition and community-based healing), and Johan Galtung’s idea of positive peace (resolving root causes of conflict), RSSM’s justice principle focuses on repairing relationships and communities. It also integrates trauma-informed insights from psychologists such as Bessel van der Kolk and Gabor Maté, recognizing that unhealed trauma (both individual and collective) often perpetuates cycles of harm. Justice as structural healing means that responding to harm involves understanding the social systems that enabled that harm (for example, poverty, racism, colonialism, patriarchy) and working to change those systems, while also addressing the immediate needs of those affected. In practice, this might translate to expanding restorative justice programs in schools and legal systems, truth and reconciliation processes in societies addressing historical injustices, and policies that focus on rehabilitation and reintegration rather than retribution. Ultimately, by treating conflict as a potentially constructive force, we shift from a punitive paradigm to one that strives for holistic healing and systemic change.

- Ecology and Society as One System – A foundational tenet of RSSM is the reintegration of human society with the natural world, treating them as one interconnected system. Human governance, culture, and economy are seen as embedded within ecological cycles and bound by the limits and principles of nature. This stands in contrast to frameworks that treat society as separate from or above nature. Drawing inspiration from ecological thinkers and indigenous knowledge, this principle emphasizes that social systems must learn from and work with natural systems. For instance, it incorporates insights from Murray Bookchin’s social ecology (which argues that nearly all of our ecological problems originate in deep-seated social issues), Vandana Shiva’s advocacy for biodiversity and traditional ecological knowledge, and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s teachings on reciprocity between humans and the earth. Decolonial and indigenous perspectives, such as those by Ailton Krenak or Arturo Escobar, also inform this view by challenging the Western notion of human dominance over nature and advocating for a pluriverse where many ways of relating to the earth coexist. By viewing ecology and society as one, RSSM posits that sustainable social systems must mirror the balance and cyclic renewal found in nature. This means policies and institutional designs explicitly account for ecological impact and are oriented toward regeneration of environmental health. In practical terms, this could lead to governance models that grant legal rights to ecosystems (as seen in movements for the Rights of Nature), economic models based on regenerative agriculture and renewable energy that align with natural cycles, and urban planning that treats cities as integrated parts of local ecosystems. Ultimately, this principle reminds us that any social transformation is incomplete if it does not also heal our relationship with the planet that sustains us.

- Change as Recursive and Emergent – RSSM understands social change as a recursive, cyclical, and emergent process, rather than as a one-time event or a simple linear progression from one state to another. Change is recursive in the sense that it feeds back into itself: transformations at one level (say, cultural values) will loop back and alter other levels (institutions, personal behaviors), which in turn influence future changes in culture – creating ongoing cycles of transformation. Change is emergent in that it results from the complex interactions of many agents and factors; it often unfolds in unpredictable ways and cannot be fully engineered or controlled from the top down. This principle moves away from viewing history purely as a series of oppositional struggles where one force wins over another, and instead sees history more like an evolving ecosystem or an iterative learning process. It’s informed by systems thinking and complexity theory, as well as by social movement theorists who emphasize iterative experimentation. For example, adrienne maree brown’s concept of Emergent Strategy (inspired in part by Octavia Butler’s science-fiction ideas about adaptive change) highlights how small-scale, adaptive changes can scale up to large transformations, and how critical it is to build resilient, adaptable movements. Achille Mbembe’s reflections on the iterative deconstruction of colonial power and Gloria Anzaldúa’s notion of nepantla (the in-between space where new consciousness can form) also resonate with the idea of recursive change that breaks old binaries and creates new syntheses. In practice, embracing change as cyclical and emergent means that activists, policymakers, and communities focus on long-term processes and learning-by-doing. Rather than expecting a single revolution or policy to “fix” society, RSSM would encourage continuous reflection, adaptation, and iterative reforms. Social transformation then becomes a series of unfolding phases – periods of upheaval and periods of stabilization – each building on one another. This principle counsels patience and persistence: even setbacks or conflicts can generate knowledge that feeds into the next cycle of change. Over time, these cycles can lead to profound systemic shifts without the process being straightforwardly linear or zero-sum.

In summary, the Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM) offers a holistic set of guiding principles for analyzing society and pursuing change. It encourages us to see governance, economy, identity, justice, and ecology not as separate silos or static structures, but as interdependent and ever-evolving subsystems of one larger living social system. Each principle reinforces the others: for instance, treating economy as a living system dovetails with seeing ecology and society as one system; viewing identity as fluid and intersectional complements the emphasis on participatory, regenerative governance that includes diverse voices; and understanding change as emergent underlies the commitment to justice as an ongoing healing process. Together, these principles form a meta-framework aimed at systemic transformation – one that is adaptive, inclusive, and attuned to both social and ecological well-being.

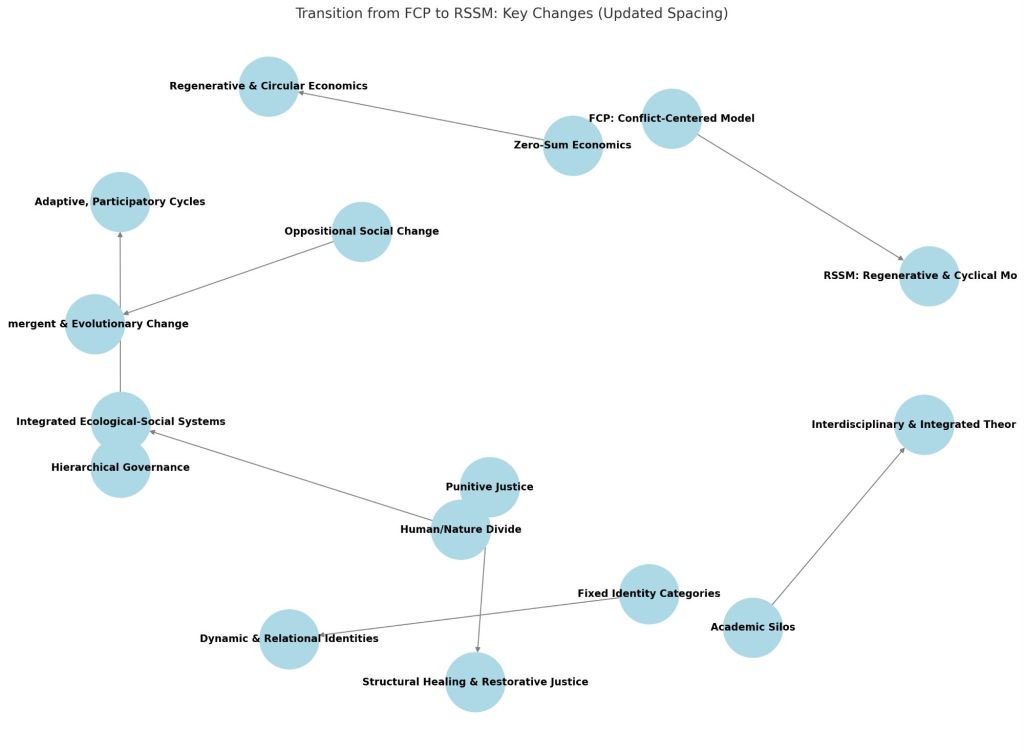

3. Outline of All Changes from the Original Framework

The transition from the original Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) to the Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM) involved numerous fundamental changes. Below we outline the key shifts that were made, explaining why each was necessary and how it improves the framework. These changes address the critiques of the original and are designed to eliminate the binary thinking, rigid hierarchies, and intellectual silos that previously limited the framework:

- From Classical Theory Constraints to Interdisciplinary Integration: The original FCP was rooted mainly in classical sociological paradigms (structural-functionalism and orthodox conflict theory), which gave it a relatively narrow theoretical scope. We recognized this as a limitation in depth and relevance. In RSSM, we expanded the theoretical foundation to integrate a much broader range of thinkers and disciplines – including critical theory, feminist theory, decolonial studies, ecology, psychology, and systems theory. This change was necessary to provide a richer, more nuanced understanding of social phenomena. By bringing in diverse intellectual traditions, we overcome academic silos. No longer confined to one school of thought, RSSM can draw connections between, for example, economic systems and psychological trauma, or between power dynamics and ecological sustainability. This interdisciplinary approach increases the framework’s explanatory power and applicability to complex real-world issues that do not fall neatly into one academic category.

- From One-Dimensional Power to Multi-Dimensional Power: FCP did not sufficiently capture the dual nature of power as both embedded in structures and enacted through everyday relations. It tended to treat power either in the classical conflict sense of one group dominating another structurally, or simply assumed a functional necessity of power hierarchies. In RSSM, we reconceptualized power as multi-dimensional – incorporating both structural power (laws, institutions, economic systems that shape outcomes) and dynamic power (the micro-level, dispersed power that operates in discourse, norms, and interpersonal relations). This shift was influenced by integrating theorists like Michel Foucault (power/knowledge and disciplinary power) alongside traditional structural analysts like Max Weber (bureaucratic authority) and Pierre Bourdieu (social and cultural capital within fields). By doing so, RSSM avoids the binary of viewing power as either top-down or purely micro; it sees power as operating on many levels simultaneously. This change was crucial because it allows analysis of how entrenched systems (say, legal structures or class stratification) are maintained or challenged through daily practices and beliefs, and vice versa. It improves the framework by giving a more dynamic account of social control and change – one that can explain, for instance, how cultural hegemony (à la Gramsci) stabilizes structural inequality, and how grassroots actions and changing narratives can, over time, destabilize and transform those structures.

- From Rigid Categories to Fluid, Relational Categories: The original framework, being influenced by older theories, risked treating social categories (like class, gender, race) in isolation or as fixed roles in a social structure (for example, bourgeoisie vs proletariat, or male vs female roles in a family, etc.). This reflected a kind of binary and rigid understanding of identity and social positions. We recognized that this was inadequate for capturing the complexity of contemporary societies. RSSM explicitly shifts to an intersectional and relational view of social categories, as described in Principle 3 (Identity as a Dynamic Process). This change means that instead of analyzing societal issues through a single-axis lens (only class or only gender, etc.), we look at how these axes intersect and how identities and group boundaries themselves are constantly reshaped. It eliminates simplistic either/or binaries – for instance, people can be both oppressors and oppressed in different contexts, and cultural identities can blend. The necessity of this change became evident to avoid blind spots (like ignoring how race and gender modify class dynamics, or how global North/South positions affect the experience of capitalism). By making identity categories fluid and emphasizing relationships, the framework can better address issues such as systemic racism, patriarchy, and other forms of oppression in an integrated way. It also fosters a more inclusive approach, acknowledging voices and experiences that classical theories might marginalize.

- From Conflict vs. Order Dualism to Conflict-as-Generative Cycles: The term “Functional Conflict Perspective” itself suggests an attempt to bridge a dualism between conflict and function/order, but it might have inadvertently maintained that dichotomy (with conflict seen as something to be managed to maintain function). In RSSM, we did away with the conflict vs. order binary altogether by reframing conflict through the lens of regeneration and emergence. Rather than seeing social conflict and social stability as opposites in a zero-sum game, RSSM views conflicts as part of the ongoing cycles of change (Principle 6) and as opportunities for structural healing (Principle 4). This means social tensions are not simply negative disruptions nor automatically functional in the old sense; they are potentially catalysts for learning and transformation. The framework no longer asks “How does conflict serve stability?” (as a functionalist might) or “Which side wins the conflict?” (as a strict conflict theorist might), but instead asks “How can conflict reveal what needs to be healed or improved in the system?” and “What new pattern might emerge from this conflict?” This shift was essential to move beyond a static view of society. It improves the framework by providing a process-oriented understanding: social systems can go through stress and conflict and emerge reorganized at a higher level of health or justice. In practical analysis, this helps us examine, say, protest movements or social crises not just as threats to social order or as inevitable class clashes, but as recursive phases in transforming governance, economic arrangements, or cultural norms.

- From Hierarchical, Mechanistic Models to Networked, Cyclical Models: The original FCP, grounded in functionalism, might have implicitly accepted rigid hierarchies (e.g., institutions ranked over individuals, or a top-down notion of social control) and a machine-like metaphor for society (each part has a set function for the stability of the whole). One of the critiques was that this worldview is too rigid and fails to capture emergent properties. In RSSM, we replaced this with a networked and cyclical understanding of systems. Inspired by systems theory and ecology, RSSM sees social systems as more like organic networks with feedback loops rather than static pyramids. For example, rather than a one-way hierarchy where policy is dictated from the top and implemented at the bottom, a regenerative governance cycle (Principle 1) suggests information and influence flow in multiple directions in repeated loops. This eliminates the presumption that higher levels are always “in charge” in a simple chain of command; instead, power and information are distributed across nodes in the network (communities, organizations, individuals) and structure emerges from their interactions. This change was necessary to align the model with contemporary understandings of complexity. It improves the framework by allowing it to analyze phenomena like social media networks influencing political power, or local initiatives scaling up to global movements – things a rigid hierarchical model struggles to explain. Moreover, it resonates with ethical shifts towards flattening harmful hierarchies: for instance, RSSM’s network approach would critique and seek alternatives to strict patriarchal family models or purely profit-driven corporate structures, replacing them with more egalitarian, collaborative configurations.

- From Anthropocentric to Ecological: A subtle but crucial change is the integration of the ecological dimension which was absent or minimal in FCP. Traditional social theories often treated human society as separate from the natural world (anthropocentrism). We realized this was a critical oversight, especially in the face of climate change and sustainability crises. RSSM embeds ecology into the core (Principle 5: Ecology and Society as One System), effectively collapsing the silo between social theory and environmental science. This shift was necessary not only to address current global challenges but also to enrich the framework’s understanding of how material conditions and environmental factors are entwined with social structures (for example, how resource extraction drives global inequalities or how environmental degradation disproportionately affects marginalized communities). By integrating ecological thought, RSSM eliminates the false division between human systems and natural systems. It also removes a hierarchy that placed humans above nature; instead, humans are part of a larger Earth system. The framework is thus improved in its ability to deal with questions of sustainable development, environmental justice, and long-term viability of social systems. It enables analysis of policies or practices in terms of both social and ecological impact, and it draws on wisdom from environmental movements to inform social change strategies (e.g., learning from ecosystem resilience to design resilient communities).

- From Static Model to Evolving Model: Finally, a meta-level change is how we view the framework itself. The original FCP was presented somewhat as a finished perspective derived from established theories. In reimagining it as RSSM, we acknowledge that this model is evolving and open-ended. This reflexive change means RSSM is explicitly a living model that will adapt as it is applied and as new insights emerge (in line with its own Principle 6 about emergent change). We broke the intellectual silo that separated “theory” from practice by intending RSSM to be used in practice and updated from feedback. This change was necessary to avoid the framework becoming yet another rigid dogma. Instead, it positions RSSM as a guiding set of principles that can learn and regenerate— in other words, the framework itself operates regeneratively. This improvement ensures that RSSM can remain relevant and inclusive, incorporating new knowledge (for example, as new social issues arise or new thinkers from previously marginalized groups contribute ideas). It embraces continuous critique and revision, much as the creation of RSSM was born out of critique of FCP.

In essence, each of these changes addresses a dimension where the original framework was lacking and replaces it with a more flexible, integrative, and forward-thinking approach. The elimination of binary thinking (such as structure vs. agency, society vs. nature, conflict vs. order) and rigid hierarchies (both in social ontology and in intellectual approach) allows RSSM to capture the nuances of power and change. Breaking out of intellectual silos means the model draws on the full range of human knowledge to inform its insights. These shifts collectively make RSSM a more powerful tool for understanding the complexities of societal transformation and for guiding action toward a more equitable and sustainable world.

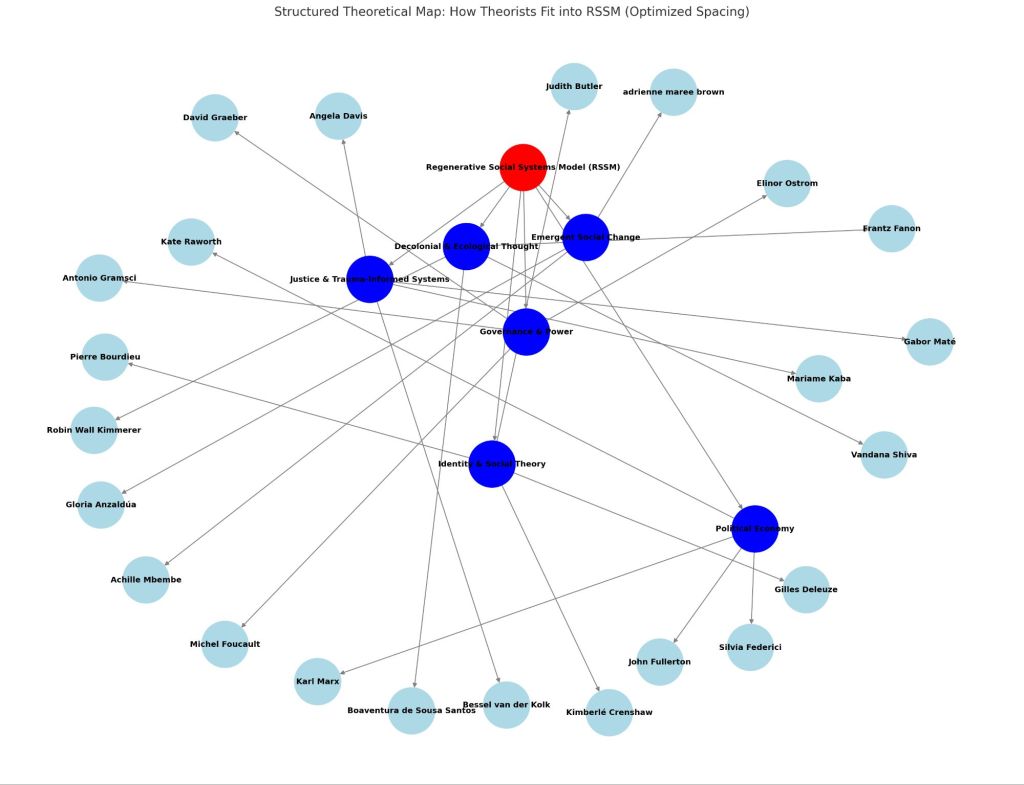

4. Comprehensive List of Theorists Integrated

A wide array of theorists and intellectual traditions have been integrated into RSSM to provide its interdisciplinary foundation. Below is a categorized list of key thinkers whose work has informed the development of the Regenerative Social Systems Model:

- Power and Governance: Michel Foucault; Antonio Gramsci; Dorothy Smith; Max Weber; Pierre Bourdieu.

*(These theorists contribute understandings of how power operates, from Foucault’s dispersed power/knowledge and disciplinary mechanisms, to Gramsci’s cultural hegemony, Smith’s feminist institutional ethnography and standpoint of the everyday, Weber’s types of authority and bureaucracy, and Bourdieu’s forms of capital and habitus that reproduce power dynamics.) - Political Economy: Immanuel Wallerstein; David Harvey; Andre Gunder Frank; Silvia Federici; Karl Polanyi.

*(This category brings in world-systems analysis (Wallerstein, Frank) to understand global economic structures, Harvey’s Marxist geography and critique of capitalism, Federici’s feminist Marxist perspective on labor and the commons, and Polanyi’s idea of the economy embedded in society and the “double movement” against market excesses.) - Post-Structuralism: Jean Baudrillard; Judith Butler; Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari; Ernesto Laclau & Chantal Mouffe.

*(These thinkers inform RSSM’s view on discourse, identity, and power. Baudrillard’s simulations and hyperreality critique how meaning is constructed; Butler provides insight into gender performativity and the fluidity of identity; Deleuze & Guattari contribute concepts of rhizomatic networks and deterritorialization, influencing the non-hierarchical modeling; Laclau & Mouffe bring in post-Marxist ideas about hegemony, discourse, and radical democracy.) - Decolonial Thought: Frantz Fanon; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak; Walter Mignolo; Dipesh Chakrabarty; Boaventura de Sousa Santos.

*(From this tradition, RSSM gains perspectives on how colonial histories shape present power structures and knowledge systems. Fanon addresses the psychological and social impacts of colonization and the possibility of decolonial revolution; Spivak questions representation and “epistemic violence” against subaltern voices; Mignolo and Santos advocate for pluriversal knowledges and delinking from Eurocentric paradigms; Chakrabarty emphasizes provincializing Europe’s historic narrative and integrating multiple temporalities in understanding modernity.) - Trauma-Informed Systems: Stephen Porges; Bessel van der Kolk; Gabor Maté; Ruth Lanius.

*(These figures introduce a psychological and neurobiological dimension, highlighting how trauma (whether personal or collective) affects human behavior and social systems. Porges’ Polyvagal Theory helps explain how people’s ability to engage socially is tied to feelings of safety; van der Kolk and Maté provide insight into how trauma and stress can shape societal issues like addiction, aggression, or illness; Lanius (a trauma researcher) offers understanding of how trauma healing can be facilitated. Their inclusion ensures RSSM accounts for the somatic and emotional underpinnings of social conflicts and the need for healing in social change.) - Restorative Justice: Angela Davis; Mariame Kaba; Howard Zehr; John Braithwaite.

*(These theorists and practitioners inform the framework’s approach to justice as healing. Davis and Kaba’s work on prison abolition and transformative justice shows how addressing harm can be done outside of carceral, punitive systems by instead focusing on community accountability and support. Howard Zehr is a pioneer of restorative justice, emphasizing repairing harm and involving all stakeholders (victims, offenders, community) in the process of justice. Braithwaite contributes with theories of reintegrative shaming and how communities can respond to wrongdoing in ways that restore social bonds. Their ideas are integral to RSSM’s concept of justice as structural healing rather than mere punishment.) - Ecological & Regenerative Governance: Vandana Shiva; Murray Bookchin; Arturo Escobar; Robin Wall Kimmerer; Ailton Krenak.

*(These thinkers bridge ecological wisdom with social theory. Vandana Shiva offers insights on ecofeminism, biodiversity, and community rights over resources against exploitative systems. Bookchin’s social ecology links environmental issues to hierarchical social structures and proposes libertarian municipalism as a political solution. Escobar brings an anthropology of development and design for the pluriverse, arguing for localized, bio-cultural approaches. Robin Wall Kimmerer, as an indigenous scientist, shares the concept of reciprocity with nature and combines traditional ecological knowledge with Western science. Ailton Krenak, an indigenous leader, challenges the Western worldview of human-nature separation and advocates for living well in harmony with the earth. These contributions ensure RSSM treats ecological sustainability and participatory governance as deeply connected.) - Emergent Social Change: adrienne maree brown; Octavia Butler; Gloria Anzaldúa; Achille Mbembe.

*(Under this category, the focus is on understanding change, imagination, and hybrid identities. adrienne maree brown’s work on Emergent Strategy provides practical guidance on how small-scale, iterative, adaptive changes can lead to big transformations, taking cues from nature’s patterns. Octavia Butler, through her speculative fiction (like the Parable series), has inspired social thinkers with ideas of adaptability, change (“God is Change”), and envisioning alternative futures beyond oppressive structures. Gloria Anzaldúa’s concept of the Borderlands and mestiza consciousness exemplifies emergent identities and new ways of thinking that arise at the intersections of cultures and oppressions, embodying change from the margins. Achille Mbembe offers a critical look at power, necropolitics, and the postcolonial state, as well as ideas about Afrofuturism and reimagining African identities and futures beyond colonial categories. Together, these figures encourage RSSM to remain imaginative, flexible, and attuned to how new possibilities can grow out of present complexities.)

This comprehensive roster of theorists demonstrates how RSSM synthesizes insights from many domains. By organizing them into categories, we can see, for example, that our framework’s power analysis draws on both classical and contemporary social theory; our economic understanding is informed by Marxist, feminist, and world-systems critiques; our notion of identity and culture is shaped by post-structural and decolonial thinkers; our approach to justice and governance incorporates activist and non-Western perspectives; and our view of change is enriched by literature, philosophy, and complexity science. This integration is what gives RSSM its robustness. It stands on the shoulders of numerous intellectual traditions, not confined to one school, and thus is equipped to tackle the interwoven challenges of modern social systems. (We acknowledge that the above list is not exhaustive – it highlights key influences, but RSSM remains open to incorporating additional thinkers as the framework evolves.)

5. Explanation of the Name Change: From FCP to RSSM

One of the most outwardly visible changes to this framework is its name – from Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) to Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM). This change in nomenclature was not just cosmetic; it reflects the profound shifts in substance and scope that we have discussed.

The name “Functional Conflict Perspective” (FCP) no longer fit the framework for several reasons. First, it was too tightly tied to classical sociology terminology. The phrase evokes mid-20th century sociological debates, essentially mashing together elements of functionalism and conflict theory. While our initial framework did attempt to reconcile those (hence the name), the growth of the framework has far surpassed those intellectual roots. Continuing to call it FCP would be misleading, because the framework now integrates far more than just functionalist and conflict views – it includes feminist theory, post-structuralism, decolonial thought, ecological science, etc. In short, the old name was too narrow and hinted at an outdated paradigm. It risked confining the perception of the framework to that old binary (function vs. conflict) that we have since moved beyond. Additionally, the word “Perspective” suggested a static viewpoint or a lens, which did not convey the action-oriented, evolving nature of what we developed.

By contrast, “Regenerative Social Systems Model” (RSSM) was chosen to encapsulate the new essence and ambitions of the framework:

- “Regenerative” emphasizes the focus on self-renewing and healing processes. This term highlights that the model is concerned with cycles that restore and sustain systems, whether it’s in governance (adaptive cycles of feedback), economy (renewable flows of resources), or community (healing from conflict). It marks a departure from static or equilibrium-based words like “functional”. Instead of assuming systems tend toward a stable function, “regenerative” assumes systems need to continuously renew themselves. This word also aligns with contemporary discourses on regenerative development, agriculture, and design – linking our social model to a broader movement of creating systems that actively improve and regenerate their environments, rather than merely sustaining or exploiting them. It signals optimism and creativity in addressing social problems: even after disruption or damage, systems can regenerate stronger.

- “Social Systems” in the name captures the comprehensive, interwoven nature of the domains we are addressing. Whereas FCP might imply a focus just on social conflict in an abstract sense, social systems makes it clear that we are examining concrete systems (governance systems, economic systems, social relations, etc.) in an integrated way. It tells the reader that this model deals with society in a holistic manner – not just one aspect like economy or politics in isolation, but the entire fabric of interacting systems that constitute human societies. The plural “systems” also underlines that there are multiple interacting subsystems (political, economic, cultural, ecological, etc.) of concern. We deliberately use “social systems” to indicate that even ecology and technology, when brought in, are considered through their integration with human social life (thus maintaining a focus on social arrangements). This phrasing moves us beyond the earlier sociology-centric language and opens the framework to interdisciplinary audiences, such as systems scientists, ecologists, policy designers, and more, who may not identify with a “perspective” but will relate to systemic models.

- “Model” signifies that RSSM is meant to be applied and continually refined, rather than a doctrinal theory set in stone. We opted for “model” to convey pragmatism and flexibility. A model is something you can use as a template or guide, adapt to different situations, and test against reality – which is exactly what we envision for RSSM. In contrast, “Perspective” or even “Theory” can sometimes imply a more fixed or purely analytical construct. By calling it a model, we emphasize that this framework has an operational side: it can inform the design of policies, institutions, and strategies. It also implies a level of abstraction that is high-level (meta-framework) but still structured enough to outline components and relationships (as a model does). Furthermore, “model” aligns with the scientific spirit of iteration; models can be updated or even transformed as new data and feedback come in. This resonates with RSSM’s emergent and recursive view of change – the framework itself is expected to undergo regeneration as it is put into practice.

In summary, Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM) as a name brings forward the key attributes of the new framework: its regenerative approach, its systemic breadth, and its status as a living, working model. The name change was essential to signal the intellectual transition and to avoid confusion with the old paradigm. It announces that we are no longer operating within the confines of classical sociological theory alone, but have built something that aspires to guide transformation in a complex, interdependent world.

Looking ahead, the vision for RSSM is ambitious. We aim to apply this model to real-world systemic redesign in various arenas:

- In governance, RSSM can inspire the creation of political institutions that are more participatory, responsive, and fused with local ecological knowledge – for example, developing community councils that manage resources regeneratively or implementing policy-making processes that include regular feedback loops from citizens.

- In economics, RSSM encourages experiments with cooperative enterprises, circular economies, and commons-based resource management. We envisage economic policies oriented towards regeneration of communities and environments (such as green new deals, solidarity economies, or indigenous-led resource stewardship) rather than mere growth of GDP.

- In social policy and justice, RSSM provides a framework for shifting towards restorative justice systems, trauma-informed social services, and conflict mediation practices that strengthen community bonds. It also could guide educational curricula that break silos, teaching students to see social, ecological, and economic issues as interconnected.

- In organizational and community development, the model can be used to audit and redesign institutions (from schools to corporations) to be more inclusive, adaptive, and life-affirming, following the principles of diversity, feedback, and regeneration.

- Finally, in scholarship and research, RSSM serves as a call for more integrative, solution-oriented approaches that cross disciplinary boundaries. It invites researchers to contribute to an evolving understanding of systemic change by incorporating insights from all fields and even non-traditional knowledge sources.

In conclusion, the Regenerative Social Systems Model (RSSM) represents a comprehensive reimagining of how we understand and work towards systemic transformation. Born out of constructive critique, enriched by a tapestry of theoretical insights, and oriented toward healing and renewal, RSSM stands as an academically rigorous yet practical meta-framework. With its new name and structure, it better captures the guiding vision: to foster societies that are adaptive, equitable, and in harmony with the natural world. The journey from FCP to RSSM illustrates the very principles of the model – through reflection, feedback, and iterative change, a more robust system has emerged. We look forward to advancing this framework and collaborating with others to apply RSSM in the service of regenerative futures.

RSSM represents a fundamental shift from old paradigms of social analysis toward a fully integrated model of social transformation. It replaces hierarchical, extractive, and oppositional models with regenerative, relational, and emergent systems thinking.

Moving forward, RSSM will continue to evolve based on:

1. Real-world applications in governance, economy, and justice.

2. Further interdisciplinary synthesis.

3. Community-based research and participatory design.

RSSM provides a roadmap for building societies that do not just sustain themselves—but actively regenerate, heal, and evolve.

New Theorists Incorporated into the Updated Meta-Framework

Our revised Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and broader meta-framework have now integrated a much wider range of interdisciplinary theorists across governance, political economy, post-structuralism, decolonial thought, trauma-informed systems, and regenerative models. Below is a categorized list of all the new theorists we have incorporated:

1. Power, Governance, and Institutional Critique

✅ Michel Foucault – Power/knowledge, biopolitics, and governmentality.

✅ Dorothy Smith – Institutional ethnography; how power operates through everyday social relations.

✅ Antonio Gramsci – Hegemony and cultural power.

✅ Max Weber – Bureaucracy, legitimacy, and authority.

✅ Pierre Bourdieu – Social capital, habitus, and symbolic power.

2. Political Economy and Global Systems

✅ Immanuel Wallerstein – World-systems theory, core-periphery economic structures.

✅ David Harvey – Neoliberalism and urban political economy.

✅ Andre Gunder Frank – Dependency theory, global economic imbalances.

✅ Silvia Federici – Feminist critiques of capitalism, reproductive labor, and the commons.

✅ Karl Polanyi – Market society critique, embedded economies.

3. Post-Structuralism and Postmodernism

✅ Jean Baudrillard – Hyperreality, simulation, and media as reality construction.

✅ Judith Butler – Gender performativity, identity as fluid and socially constructed.

✅ Deleuze & Guattari – Rhizomatic thinking, deterritorialization, anti-Oedipal power structures.

✅ Ernesto Laclau & Chantal Mouffe – Post-Marxist discourse theory, radical democracy.

4. Decolonial Thought and Indigenous Knowledge Systems

✅ Frantz Fanon – Decolonization, psychological effects of colonial rule.

✅ Gayatri Spivak – Subaltern studies, epistemic violence.

✅ Walter Mignolo – Decoloniality, border epistemologies.

✅ Dipesh Chakrabarty – Provincializing Europe, postcolonial historiography.

✅ Boaventura de Sousa Santos – Epistemologies of the South, legal pluralism.

5. Trauma-Informed Systems and Nervous System Regulation

✅ Stephen Porges – Polyvagal theory, nervous system regulation in governance.

✅ Bessel van der Kolk – Trauma and body-memory integration.

✅ Gabor Maté – Addiction, trauma, and systemic distress.

✅ Ruth Lanius – Complex PTSD, relational repair models.

6. Restorative Justice and Conflict Transformation

✅ Angela Davis – Abolitionist frameworks, prison-industrial complex critique.

✅ Mariame Kaba – Transformative justice and community-led conflict resolution.

✅ Howard Zehr – Restorative justice models, victim-offender reconciliation.

✅ John Braithwaite – Reintegrative shaming, restorative legal frameworks.

7. Ecological and Regenerative Governance

✅ Vandana Shiva – Indigenous ecological knowledge, food sovereignty.

✅ Murray Bookchin – Social ecology, municipalism.

✅ Arturo Escobar – Pluriverse, post-development, and relational ecology.

✅ Robin Wall Kimmerer – Indigenous ecological knowledge, reciprocity in governance.

✅ Ailton Krenak – Indigenous futurism, relational land governance.

8. Social Change as Non-Linear and Emergent

✅ Adrienne Maree Brown – Emergent strategy, fractal systems of social change.

✅ Octavia Butler – Change as a recursive and adaptive process.

✅ Gloria Anzaldúa – Borderlands theory, fluidity in identity and social transformation.

✅ Achille Mbembe – Necropolitics, colonial continuities in governance.

Summary of Theoretical Expansions

We have now fully integrated governance, political economy, decoloniality, trauma-informed systems, conflict transformation, ecological governance, and emergent social change into a single meta-framework that eliminates Cartesian dualism and embraces relational, networked, and regenerative thinking.