Refining the Bio-Psycho-Social Model of Mental Wellness with FCP & MIT

The Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) offer a universal and adaptive model of mental wellness by integrating biological, psychological, and social factors into a single, cohesive framework. Unlike traditional Western psychological models that often pathologize distress and treat symptoms in isolation, FCP and MIT recognize that healing is relational, systemic, and culturally embedded. This approach allows for a more flexible, trauma-informed, and globally inclusive model of emotional and psychological well-being.

At the biological level, mental health is deeply linked to nervous system regulation, somatic awareness, and physiological responses to stress. Many Western mental health models, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), focus on top-down cognitive restructuring, assuming that thoughts control emotions. However, FCP and MIT acknowledge that for many individuals, especially those who have experienced trauma or belong to neurodivergent populations, emotional responses emerge from the body first (bottom-up processing). This aligns with research in Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 2011), which highlights that nervous system states dictate emotional and cognitive patterns, not the other way around. In this model, FCP regulates stress and response patterns through adaptive learning, while MIT enhances self-awareness through interoception (body awareness).

At the psychological level, mental wellness is shaped by cognition, emotional regulation, and identity formation. Traditional therapy often assumes that individuals can independently change thought patterns, but FCP introduces the idea that distress is often a functional response to an external conflict—whether that be internal contradictions, relational dynamics, or systemic oppression. FCP teaches individuals to see conflict as a learning opportunity rather than something to suppress or avoid. Meanwhile, MIT encourages self-reflection, allowing individuals to recognize how their internal emotional states mirror external conditions—a perspective aligned with many Eastern and Indigenous healing practices that view personal transformation as inherently linked to social and environmental conditions.

At the social level, mental health cannot be separated from relationships, cultural belonging, and systemic influences. Many mainstream Western psychological frameworks prioritize individual healing over collective healing, often ignoring how communities, economic systems, and historical trauma shape personal well-being. In contrast, FCP frames conflict as a functional mechanism for social stability, rather than simply seeing distress as an individual disorder. MIT expands this by recognizing how self and society mirror each other, creating an interconnected feedback loop between personal experiences and social conditions. This aligns with Indigenous concepts of relational healing, Ubuntu philosophy (“I am because we are”), and collectivist mental health approaches that emphasize community support over individual pathology.

Together, FCP and MIT integrate into a trauma-informed model of growth that is both personal and systemic. By incorporating collectivist healing traditions, such as storytelling, somatic regulation, ritualized grief processing, and relational accountability, this framework ensures that mental wellness is not detached from cultural realities. Instead of imposing Western pathology-based diagnostic systems, this model honors the diverse ways in which humans regulate emotions, heal from conflict, and build resilience within their social environments.

The final outcome of this model is Holistic Mental Wellness—an adaptive, non-pathology-based healing system that recognizes distress as a signal for change rather than a disorder to be suppressed. By combining biological regulation, psychological adaptation, and social integration, this framework provides a more realistic, inclusive, and effective approach to emotional and psychological health across cultures, neurotypes, and lived experiences.

FCP & MIT: A Universal and Multicultural Bio-Psycho-Social Approach to Mental Health & Emotional Wellness

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) offer a universal and multicultural approach to mental health and emotional wellness because they do not impose a rigid, culturally-specific model of psychological healing. Instead, they recognize that mental and emotional well-being are deeply embedded in biological, psychological, and social systems that vary across individuals, communities, and cultures. This makes them adaptive, inclusive, and capable of integrating diverse perspectives rather than enforcing a one-size-fits-all model like many Western psychological frameworks.

1. FCP: A Global Lens on Conflict as Growth

FCP challenges the pathology-based approach to mental health, where symptoms are viewed as individual dysfunctions, and instead recognizes conflict, distress, and dysregulation as functional parts of human adaptation and social systems. This aligns with many indigenous, Eastern, and collectivist cultural traditions that see mental wellness as deeply tied to relationships, community harmony, and environmental balance.

Why FCP is Universally Applicable:

Biological: Conflict and stress responses are natural regulatory mechanisms in the nervous system. Trauma is not just a psychological issue—it has biological and physiological consequences.

Psychological: Different cultures frame conflict differently—some encourage direct confrontation (Western individualism), while others emphasize relational harmony (collectivist cultures). FCP does not dictate which approach is “correct” but instead asks, “What function does this serve in this system?”

Social: FCP sees emotional regulation as relational, not just individual. This mirrors indigenous and collectivist healing practices where mental health is embedded in rituals, shared experiences, and community storytelling.

Rather than prescribing Western cognitive frameworks (like CBT), which prioritize individual thought restructuring, FCP allows for diverse healing models, whether that be:

✔ Community-based conflict resolution (African restorative justice models)

✔ Ritualized grieving and collective healing (Indigenous mourning practices)

✔ Mindfulness and balance-based wellness (Buddhist and Daoist traditions)

FCP ensures that mental health interventions align with the natural conflict resolution and healing mechanisms of a given cultural or personal context, rather than imposing Western pathology-based definitions of disorder.

2. MIT: A Universal Model of Self & System Integration

Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) bridges the gap between personal healing and systemic transformation. It recognizes that an individual’s mental and emotional wellness is deeply influenced by their social, historical, and cultural environment. This aligns with many non-Western traditions that do not see the self as separate from the system but as an interdependent part of the whole.

Why MIT is Universally Applicable:

Biological: Self-awareness is rooted in the nervous system and interoception—all humans, regardless of culture, experience emotions in response to internal (body state) and external (social/environmental) factors.

Psychological: MIT does not assume a fixed self (a Western concept) but instead recognizes identity as fluid and relational—which aligns with many indigenous and Eastern spiritual traditions where the self is seen as constantly evolving and interconnected.

Social: Many non-Western healing traditions view mental distress as a sign of social imbalance rather than individual pathology. MIT’s model of mutual mirroring reflects this perspective, as it understands that when a system is dysfunctional, individuals absorb and reflect that dysfunction. Healing must happen both internally and externally.

Rather than forcing individuals to “adjust” to unhealthy social structures (as Western psychology often does), MIT validates the lived experience of oppression, intergenerational trauma, and systemic harm while simultaneously helping individuals reclaim personal agency in shaping the system they exist within.

This mirrors:

✔ Ubuntu Philosophy (Southern Africa): “I am because we are”—emphasizing interdependence and relational healing.

✔ Buddhist & Hindu Karma Models: The idea that actions and experiences are reflections of both past and present interconnectedness.

✔ Indigenous Wisdom Traditions: The belief that healing the individual requires healing the community and vice versa.

By grounding self-awareness in relational and systemic consciousness, MIT allows for multi-layered healing that is not confined to one cultural paradigm.

3. The Bio-Psycho-Social Intersection: FCP & MIT as a Holistic Framework

When combined, FCP and MIT create a holistic, universally applicable approach that integrates biology, psychology, and social dynamics in a way that respects cultural diversity while maintaining a functional core framework.

How FCP & MIT Bridge Bio-Psycho-Social Healing Across Cultures:

✔ FCP addresses biological & nervous system regulation → Conflict and stress are not just emotional; they are bodily responses that require somatic, relational, and environmental regulation.

✔ MIT enhances self-awareness & interconnection → Healing is not about “fixing” the individual but understanding how they reflect and are reflected by their environment.

✔ Together, they integrate systemic and personal healing → Individuals learn to work with, rather than against, their cultural, biological, and relational realities.

Unlike rigid, Western-dominant approaches to psychology, which often attempt to universalize Eurocentric cognitive frameworks, FCP and MIT provide a flexible, adaptive framework that can be applied across cultures, traditions, and individual needs.

By shifting away from top-down, pathology-based models (CBT, DSM categories, Western trauma responses) and into dynamic, bottom-up, relational healing models, FCP and MIT offer an approach to mental health that is not only more inclusive but also more scientifically accurate in accounting for the full human experience.

Final Thought: The Future of Mental Health is Adaptive, Not Prescriptive

As the world becomes more interconnected, it is crucial to move beyond rigid, one-size-fits-all mental health models that prioritize Western pathology-based perspectives.

✔ FCP teaches us how to navigate and learn from conflict across cultural contexts.

✔ MIT helps us integrate personal awareness with systemic healing in a way that is universally relevant.

✔ Together, they provide a bio-psycho-social foundation for emotional wellness that respects cultural diversity and the complexity of the human experience.

This is the future of trauma-informed, culturally responsive mental health and emotional wellness.

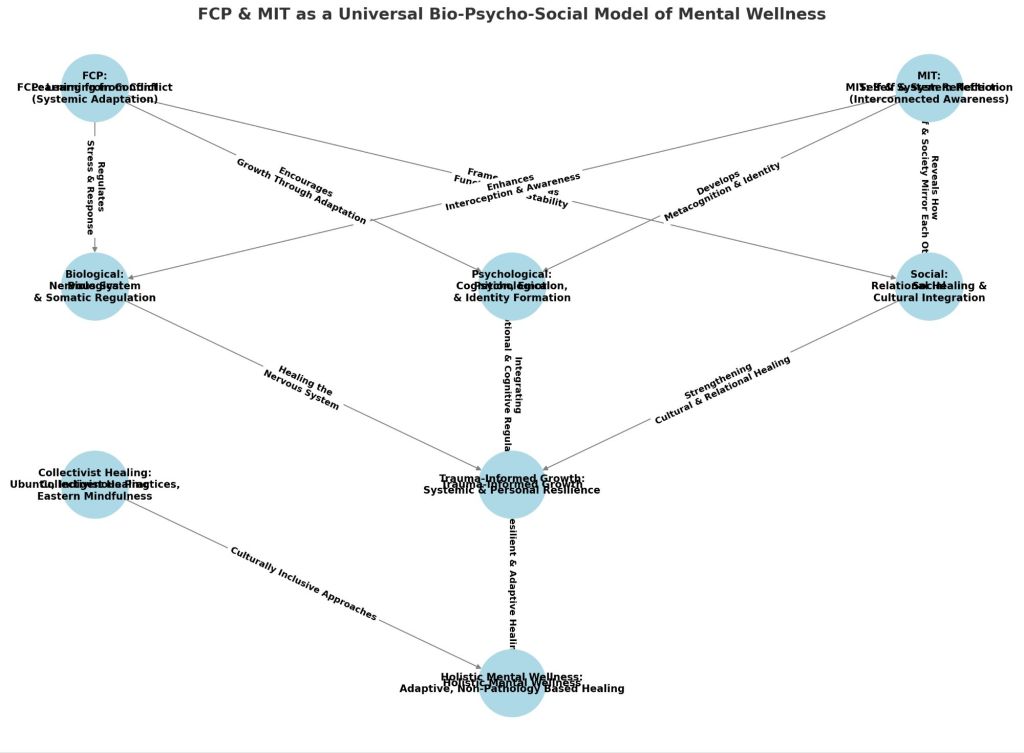

Here is a visual framework showing how FCP & MIT integrate across biological, psychological, and social dimensions in a global mental health model:

Top-Level Nodes (Main Concepts in Blue Circles)

1. FCP: Learning from Conflict – “Systemic Adaptation”

2. MIT: Self & System Reflection – “Interconnected Awareness”

Bio-Psycho-Social Levels

3. Biological – “Nervous System & Somatic Regulation”

4. Psychological – “Cognition, Emotion, & Identity Formation”

5. Social – “Relational Healing & Cultural Integration”

Integrated Healing & Growth

6. Trauma-Informed Growth – “Systemic & Personal Resilience”

7. Collectivist Healing – “Ubuntu, Indigenous Practices, Eastern Mindfulness”

8. Holistic Mental Wellness – “Adaptive, Non-Pathology Based Healing”

Labels of Intersecting Lines (Connections Between Concepts)

FCP → Biological – “Regulates Stress & Response”

FCP → Psychological – “Encourages Growth Through Adaptation”

FCP → Social – “Frames Conflict as Functional for Stability”

MIT → Biological – “Enhances Interoception & Awareness”

MIT → Psychological – “Develops Metacognition & Identity”

MIT → Social – “Reveals How Self & Society Mirror Each Other”

Biological → Trauma-Informed Growth – “Healing the Nervous System”

Psychological → Trauma-Informed Growth – “Integrating Emotional & Cognitive Regulation”

Social → Trauma-Informed Growth – “Strengthening Cultural & Relational Healing”

Trauma-Informed Growth → Holistic Mental Wellness – “Resilient & Adaptive Healing”

Collectivist Healing → Holistic Mental Wellness – “Culturally Inclusive Approaches”

This map illustrates how FCP and MIT form a universal, cross-cultural approach to mental health by integrating biological regulation, psychological adaptation, and social healing into a flexible and trauma-informed framework.

What This Model Shows:

FCP (Functional Conflict Perspective) and MIT (Mirror Integration Theory) integrate across biological, psychological, and social dimensions to create a holistic approach to healing.

Biological Level → FCP regulates stress responses, while MIT enhances interoception (self-awareness of body states).

Psychological Level → FCP promotes adaptation and resilience, while MIT deepens metacognition and identity awareness.

Social Level → FCP frames conflict as functional, while MIT reveals how self and society mirror each other for healing.

Trauma-Informed Growth connects all three levels, bridging neuroscience, emotional regulation, and relational healing.

Collectivist Healing Traditions (Ubuntu, Indigenous practices, Eastern mindfulness) reinforce culturally responsive approaches to mental wellness.

The outcome is Holistic Mental Wellness → a non-pathology-based, adaptive model for emotional and psychological well-being across diverse cultures.

This framework moves beyond Western psychology’s pathology-driven models (CBT, DSM categories, rigid cognitive restructuring) and instead creates a flexible, adaptive healing approach applicable to diverse cultures and personal experiences.

Here is a list of citations and references that support my Bio-Psycho-Social Model of Mental Wellness integrating Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT):

Neuroscience & Nervous System Regulation (Biological Level)

1. Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Explains how nervous system states dictate emotional regulation and social connection.

2. Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Discusses bottom-up trauma processing and the role of the body in emotional healing.

3. Schore, A. N. (2019). Right Brain Psychotherapy. W.W. Norton & Company.

Explores how affective neuroscience and right-brain development influence emotional resilience.

Cognition, Emotional Regulation & Identity Formation (Psychological Level)

4. Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

Introduces the growth mindset concept, which aligns with FCP’s conflict-as-learning approach.

5. Flavell, J. H. (1979). “Metacognition and Cognitive Monitoring: A New Area of Cognitive-Developmental Inquiry.” American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911.

Defines metacognition, a key concept in MIT’s self-reflective awareness model.

6. Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

Explores attachment theory and how early relationships shape emotional and cognitive responses.

7. Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum.

Provides empirical studies on attachment styles, which influence how individuals process emotional distress.

Relational Healing, Collectivist Mental Health & Cultural Integration (Social Level)

8. Tomasello, M. (2014). A Natural History of Human Thinking. Harvard University Press.

Highlights how human cognition evolved as a collective, relational process rather than an individual function.

9. Kirmayer, L. J., & Swartz, L. (2013). “Culture and Global Mental Health.” Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(6), 763–789.

Critiques Western mental health models and advocates for culturally responsive, relational healing approaches.

10. Watters, E. (2010). Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche. Free Press.

Examines how Western psychological frameworks impose pathology-based mental health models on non-Western cultures.

11. Tutu, D. (1999). No Future Without Forgiveness. Image.

Discusses Ubuntu philosophy and the role of reconciliation in collective emotional healing.

12. Gone, J. P. (2013). “Redressing First Nations Historical Trauma: Theorizing Mechanisms for Indigenous Culture as Mental Health Treatment.” Transcultural Psychiatry, 50(5), 683–706.

Explores Indigenous healing practices that prioritize relational and systemic healing over individual pathology.

Trauma-Informed & Systemic Healing Approaches

13. Maté, G. (2022). The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture. Avery.

Examines how trauma is not just personal but shaped by cultural, economic, and systemic structures.

14. Foucault, M. (1961/1988). Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. Vintage.

Critiques how Western institutions define and regulate mental illness.

15. Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Challenges the Eurocentric narrative of hierarchical social structures and presents alternative models of collective governance and healing.

Intersection of FCP & MIT with Systemic Change

16. Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Aligns with FCP’s framework of learning from conflict as a path to liberation and systemic transformation.

17. Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Harvard University Press.

Explores how social structures shape individual thought and reinforce systemic hierarchies.

18. Chomsky, N., & Herman, E. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. Pantheon.

Demonstrates how systems shape collective consciousness, linking to MIT’s self-system mirroring.

Key Takeaways from These Sources:

Neuroscientific research supports FCP’s and MIT’s emphasis on bottom-up nervous system regulation.

Cognitive and psychological studies validate growth mindset, metacognition, and relational identity formation.

Cross-cultural research critiques Western pathology-based psychology and highlights the importance of collectivist healing models.

Social theory provides insight into how mental health is shaped by systemic and historical factors, aligning with MIT’s framework of mutual mirroring.

How These Citations Strengthen the Bio-Psycho-Social Model

1. They provide empirical and theoretical evidence supporting FCP’s conflict-based growth model and MIT’s reflective mirroring model.

2. They validate bottom-up nervous system regulation as a key factor in emotional resilience.

3. They challenge Western pathology-based approaches and emphasize cultural adaptability.

4. They integrate neuroscience, psychology, and sociology into a holistic model of mental wellness.