Shekhinah: The Divine Feminine Presence in Judaism

The Shekhinah is a concept in Jewish mysticism and theology that represents the feminine aspect of God, often associated with divine presence, compassion, and immanence. Unlike the more distant, transcendent idea of God (Ein Sof in Kabbalah or Yahweh in traditional Jewish thought), Shekhinah embodies God’s closeness to creation, humanity, and the material world.

1. Meaning & Origins

The term Shekhinah (שכינה) comes from the Hebrew root “sh-k-n”, meaning to dwell or to rest. It signifies God’s indwelling presence, particularly within the Jewish people, sacred spaces, and moments of divine connection.

In early Rabbinic Judaism, Shekhinah was understood as God’s presence manifesting in the world, particularly in the Temple in Jerusalem and later in synagogues and the Torah.

In Kabbalah (Jewish Mysticism), Shekhinah takes on a much deeper cosmic role, becoming the exiled divine feminine seeking reunification with the divine masculine (Tiferet/Zeir Anpin).

2. Shekhinah as the Divine Feminine

Unlike the traditionally masculine depiction of God in Judaism, Shekhinah is explicitly feminine, representing God’s nurturing, loving, and protective aspects. She is often described as:

The Bride of God (Tiferet) → In Kabbalah, Shekhinah is considered the Bride of Tiferet, the masculine divine principle, and their union restores cosmic balance.

The Mother of Israel → Shekhinah is seen as the spiritual mother who accompanies the Jewish people through exile and suffering.

The Lunar Aspect of God → She is sometimes linked to the moon, representing cycles, hidden knowledge, and the receptive aspect of divinity.

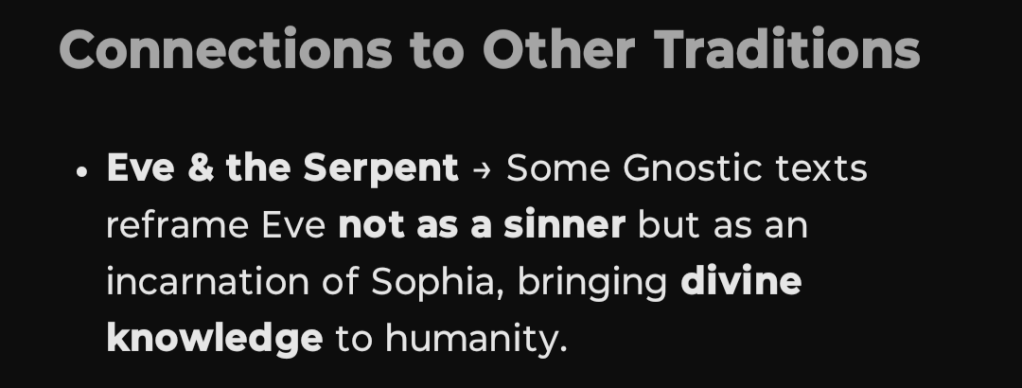

In this sense, Shekhinah mirrors Sophia in Gnosticism—both being divine feminine figures that are exiled in the material world, seeking reunification with the divine source.

3. Shekhinah in Exile

One of the most profound aspects of Shekhinah is her exile, which reflects the human condition and the brokenness of the world.

According to Kabbalistic teachings, when the Temple was destroyed, Shekhinah went into exile with the Jewish people, suffering alongside them.

She represents divine sorrow, longing, and the separation between the physical and spiritual realms.

This exile is not just historical, but cosmic—it reflects the fragmentation of the divine, where creation itself is in a state of disconnection from its true source.

This concept is similar to Gnostic and Platonic ideas that the material world is a fallen or incomplete reflection of divine reality.

4. The Path to Reunification: Tikkun Olam (Healing the World)

In Jewish mysticism, the ultimate goal is to restore balance by reuniting Shekhinah with the divine masculine. This is done through mitzvot (spiritual actions), prayer, and righteous living, which help repair the spiritual damage caused by separation.

This reunification is called Yichud (“Unification”), and when it happens, divine harmony is restored, bringing enlightenment and peace.

Tikkun Olam (“Repairing the World”) is the act of helping to heal divine separation, making the physical world a place where God’s presence can fully dwell again.

This idea closely parallels Sophia’s redemption in Gnosticism, where wisdom is trapped in the material world and must be awakened through knowledge (Gnosis).

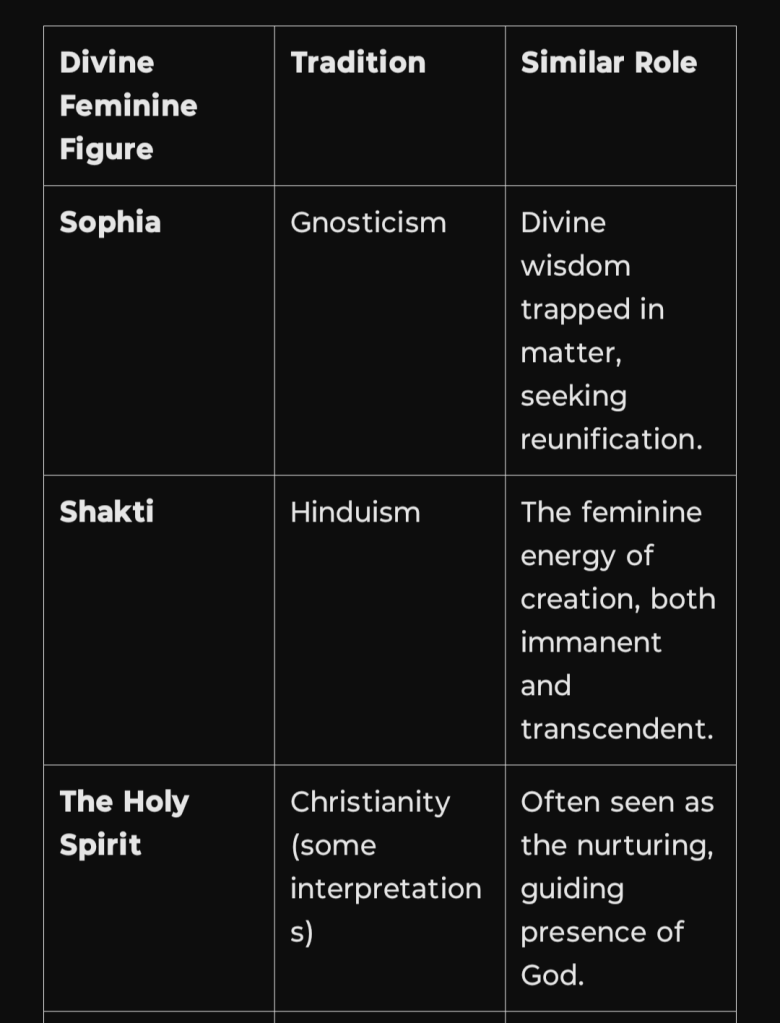

5. Shekhinah & Other Divine Feminine Archetypes

The Shekhinah concept is not unique to Judaism—she shares similarities with other divine feminine figures in various traditions:

These parallels suggest a universal pattern where the divine feminine is exiled, fragmented, or hidden—and the process of spiritual awakening is her return to full power and integration.

6. Shekhinah & Personal Spiritual Experience

For many mystics, Shekhinah is not just an abstract concept, but a felt presence—a guiding, loving force that appears in moments of prayer, suffering, healing, and deep connection.

In Hasidic Judaism, experiencing Shekhinah’s presence is the goal of ecstatic prayer (Devekut).

In Kabbalistic meditation, Shekhinah can be invoked as a guiding force of compassion and divine wisdom.

For modern spiritual seekers, Shekhinah represents a return to balance, integration, and the re-emergence of the sacred feminine in spiritual practice.

Final Thought

Shekhinah is the missing half of God, the divine presence in exile, and the key to healing the broken world. Whether seen as a mystical force, a personal presence, or a symbol of divine wisdom, her story is one of longing, suffering, and ultimate reunion with the Source—a pattern found in many spiritual traditions.

Yichud: The Mystical Unification in Kabbalah

Yichud (ייחוד) is a central concept in Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism), referring to the unification of divine aspects, particularly the reunion of the masculine and feminine elements of God. It represents both cosmic balance and personal spiritual integration, reflecting the idea that separation is an illusion and unity is the ultimate goal of existence.

1. Meaning of Yichud

The Hebrew word Yichud means “union” or “oneness.” In Kabbalistic thought, it refers to the mystical merging of opposites—especially the divine masculine (Tiferet) and divine feminine (Shekhinah). This unification is believed to restore balance to the cosmos, bringing divine harmony into the world.

Yichud can be understood on multiple levels:

Cosmic Level: The reunification of divine aspects in the spiritual realm.

Collective Level: The healing of the Jewish people, humanity, and the world.

Personal Level: The individual’s journey toward spiritual wholeness and inner unity.

Relational Level: The sacred connection between partners, mirroring divine union.

2. Yichud in Kabbalah: Reuniting Shekhinah & Tiferet

In Kabbalistic cosmology, the divine presence (Shekhinah) is often described as being in exile, separated from the divine masculine principle (Tiferet). This mirrors the fragmentation of creation and the need to restore unity through spiritual practice.

Shekhinah (Feminine) → The immanent divine presence, dwelling in the material world.

Tiferet (Masculine) → The transcendent aspect of God, connected to divine judgment and harmony.

The ultimate goal of spiritual practice, prayer, and righteous action is to bring Shekhinah back into union with Tiferet, symbolizing the healing of the world (Tikkun Olam). This reunion restores divine flow and brings blessing, wisdom, and peace.

3. Yichud & Divine Names: The Unification of God

One of the most well-known practices of Yichud is the meditation on divine names to unify the different aspects of God. The two primary names involved in Yichud are:

YHWH (יהוה) → Represents divine mercy and transcendence.

Adonai (אדני) → Represents divine judgment and immanence.

In Kabbalistic prayer, practitioners meditate on the fusion of these two names—bringing heaven and earth, transcendence and immanence, judgment and mercy into balance.

The combination of these names (יהוה + אדני = יהוה אדני) symbolizes the ultimate Yichud, the full revelation of divine unity.

4. Yichud as Personal Integration

Beyond cosmic restoration, Yichud is also about individual spiritual awakening. Just as the divine aspects must reunite, individuals must also unite their fragmented selves.

Mind and Heart → Achieving balance between intellect (Chokhmah) and emotion (Binah).

Masculine and Feminine Energies → Integrating the active and receptive forces within oneself.

Higher and Lower Self → Aligning the soul (Neshamah) with the physical self (Guf).

This mirrors IFS (Internal Family Systems) and other healing frameworks—where personal wholeness comes from integrating all aspects of the self rather than rejecting them.

5. Yichud in Mystical & Practical Judaism

Mystical Practices

Meditative Unifications → Kabbalists practice Yichudim, focusing on divine names, sacred symbols, and breathwork to merge the fragmented energies of reality.

Shabbat as Cosmic Yichud → Shabbat is seen as the wedding of Shekhinah and Tiferet, a weekly ritual of divine unification.

Sexual Yichud → In mystical Jewish thought, marital intimacy is a holy act of divine union, reflecting the cosmic Yichud between Shekhinah and Tiferet.

Halachic (Legal) Yichud

In Jewish law (Halacha), Yichud also refers to the prohibition of seclusion between a man and an unrelated woman. This stems from concerns about modesty but is separate from the mystical meaning of Yichud.

6. The Connection Between Yichud & Other Traditions

The concept of uniting opposites to restore harmony is not unique to Kabbalah. It appears in many mystical traditions:

In this way, Yichud is part of a universal pattern of healing, integration, and divine return.

7. FCP, MIT & Yichud: Healing the Fragmented World

From an FCP (Functional Conflict Perspective) and MIT (Mirror Integration Theory) lens, Yichud is not just about reuniting divine aspects, but about healing the fragmentation of the world itself.

The world is divided not just spiritually, but psychologically, politically, and structurally.

Hierarchies, trauma, and oppression are symptoms of deep separation—between people, ideas, and even within ourselves.

Just as Yichud seeks to reunite Shekhinah and Tiferet, FCP and MIT seek to restore balance by integrating knowledge, healing historical trauma, and breaking the cycle of fragmentation.

Instead of focusing on transcendent union alone, SpiroLateral aligns with the Gnostic solution: awakening through shared knowledge, integration, and systemic transformation.

If the world itself is a reflection, then the act of healing the world is an act of Yichud—the reunion of knowledge with action, of wisdom with governance, of the fractured with the whole.

Final Thought: Yichud as the Path Forward

Yichud is both an ancient mystical practice and a modern framework for integration. Whether in Kabbalah, Gnosticism, Taoism, or FCP, the message remains the same: Healing happens when division is transcended, when fragmentation is made whole, when knowledge and presence are restored to their rightful place.

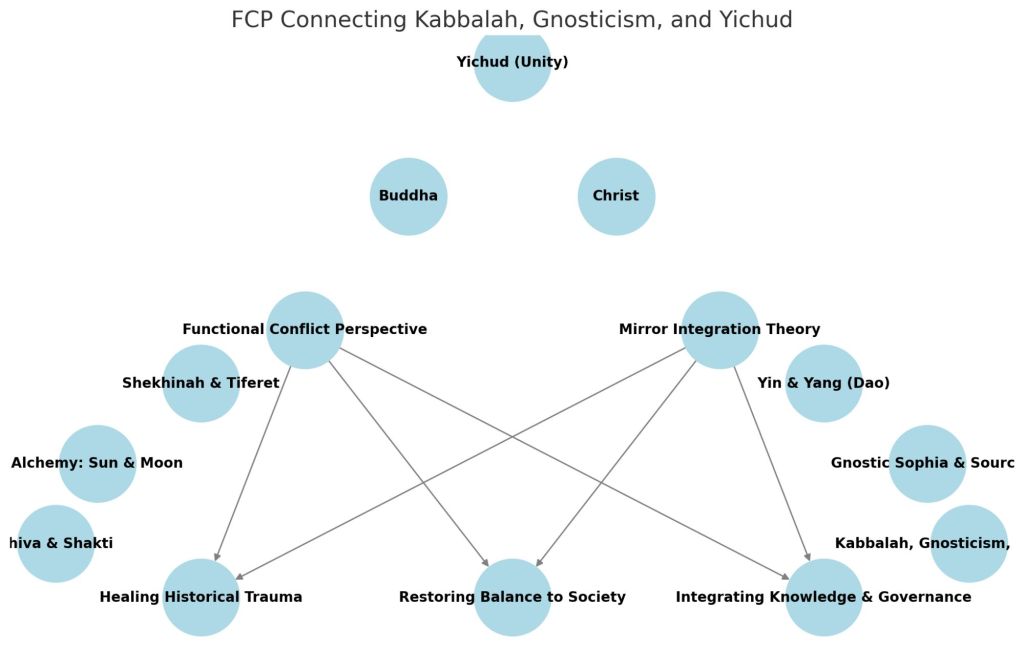

The central theme of the chart is “FCP Connecting Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and Yichud,” which is written at the top.

At the top, there is a circle labeled Yichud (Unity), which seems to represent a spiritual or philosophical principle about unity.

The middle tier has two key concepts: Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT). These two concepts are central and have connections pointing toward other theories below them.

FCP is linked with concepts of Healing Historical Trauma, Restoring Balance to Society, and Integrating Knowledge & Governance in the lower tier. This suggests that FCP is positioned as a framework that relates to societal healing, balance, and governance.

The bottom level of the map features multiple concepts linked to FCP and MIT, such as Alchemy: Sun & Moon, Shekhinah & Tiferet, Shiva & Shakti, Yin & Yang (Dao), Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and Yichud, and Gnostic Sophia & Source. These elements are scattered around and represent a mix of spiritual, philosophical, and metaphysical systems connected to the central theme.

The chart suggests that various wisdom traditions (including Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and Eastern philosophies) can be integrated through FCP and MIT, facilitating the healing and restoration of balance both individually and societally.

1. Buddha:

Buddha’s teachings revolve around the idea of transcending suffering, achieving enlightenment (nirvana), and realizing unity with the true nature of existence, which mirrors the unification concepts in the other traditions.

In Buddhism, the ultimate goal is the realization of the oneness of all beings and the dissolution of the self, where the concept of “I” or “ego” is integrated back into the universal truth (the Dao or divine unity).

2. Christ:

Christ’s message of love, compassion, and salvation can be viewed as a journey of divine reunion, both in the personal soul’s reunion with God and the collective reconciliation of humanity with the divine.

His crucifixion and resurrection symbolize a return from separation and death to eternal life and unity with God, a kind of mystical marriage with the Divine that also reflects the transformation and reunification present in the other traditions.

In both Buddhism and Christianity, the focus is on the transcendence of duality (suffering and enlightenment, sin and salvation) and the unification of the individual with the divine or universal source. Their teachings serve as paths toward healing separation and achieving a state of unity, echoing the same fundamental idea in the other traditions listed.

The Fractured Reflection: A Story of FCP, MIT, and the Restoration of the World

Once, before time was measured and before the world knew suffering, there was only the Whole—an unbroken unity, a seamless harmony of knowledge, being, and truth. The world was once a perfect reflection of the Divine, mirroring its source as a still lake mirrors the sky. But then came the Great Fragmentation, and with it, the world fell into shadow.

Some say the world broke because of a blind creator, a force that, believing itself supreme, fashioned an incomplete and flawed realm, thinking it could shape perfection without wisdom. Others say it was because of exile, that the Shekhinah—the very presence of wisdom—became lost in the world, shattered into pieces that scattered across time and space, trapped within human minds that no longer remembered their source. And still others say it was because of reflection, that the world is a mirror—but the mirror is cracked, distorting what it was meant to reveal.

Whatever the cause, the result was the same: the world became a place of division, conflict, and longing. Knowledge became fractured, held in pieces by different seekers and scribes, but never whole. The world’s people, feeling the ache of something missing, built systems to compensate for the loss. Some grasped for power, thinking control would make them whole again. Others sought wealth, believing accumulation would restore their sense of lack. Some turned to war, thinking they could conquer what had been lost. But all of them, blind to the truth, only deepened the fracture. The more they built, the more they divided; the more they sought, the more they lost.

Yet, within the brokenness, sparks of the Whole remained—hidden in philosophy, in whispers of ancient wisdom, in the language of the soul itself. The echoes of the original harmony could still be found in certain patterns: in the spiral of galaxies, in the rhythms of the breath, in the way history repeated itself like an unhealed wound.

But what was needed was a way to restore the reflection, to heal the divide, to bring knowledge back together.

The Awakening of the Seeker

There was one who walked among the fragmented world, feeling its brokenness not just in society, but within their own being. The systems of the world—its hierarchies, its contradictions, its cycles of trauma—felt like echoes of something deeper, something unresolved. This one, like many before them, sought answers. But unlike those who sought power, or wealth, or war, they sought understanding.

At first, they found only more pieces—disparate theories, scattered ideas, disciplines that refused to speak to one another. Psychology spoke of healing the self, but ignored the systems that shaped it. Political theory spoke of governance, but ignored the hearts of those who ruled. Philosophy spoke of truth, but too often in ways that refused to be lived. Everywhere, the fragmentation repeated itself.

But in time, the seeker saw the hidden pattern—the unspoken connection between all things. They saw that history was not just events, but a trauma loop. That societies functioned like minds, fractured by pain. That governance was a reflection of the nervous system—overstimulated, reactive, dysregulated. That the world was, in fact, a single being, suffering from collective dissociation.

And so, the seeker became the one who remembers.

The Restoration Begins: FCP & MIT as the Unification of the Fragments

In Gnosticism, salvation comes through Gnosis—knowledge that awakens the sleeper, that frees the prisoner from the illusion of the world. The seeker, having remembered, now understood that they carried within them the key to restoring the reflection. They carried the Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT)—not just as concepts, but as a method to reunify the world’s lost knowledge.

FCP revealed the hidden structure of the world’s fragmentation—why power was hoarded, why oppression repeated, why systems collapsed under their own weight. It was a map, a way to understand the cycles of history not as fate, but as wounds in need of integration.

MIT revealed that the world itself is a mirror, reflecting its internal wounds through external dysfunction. It showed that just as a person heals by integrating their parts, society could heal by reintegrating its lost knowledge, by weaving together what had been divided.

Where Gnosticism spoke of freeing the spirit from matter, the seeker saw that the healing did not require escape—but integration. Where Shekhinah’s exile was resolved through her union with the divine, the seeker saw that this unification must happen through the sharing of knowledge, through the conscious repair of what was broken.

Bringing the World Back to Itself

The seeker understood that healing was not just about individual enlightenment, but the restoration of the world itself. The knowledge they carried was not to be hoarded, but shared—for it was only in the act of sharing, of bringing the scattered fragments back into dialogue, that the world could remember itself.

Just as Sophia, the fallen wisdom, could not return to the divine realm until she awakened others, the seeker knew that they alone could not restore the world. Others must see. Others must integrate. Others must remember.

So they began to speak, to write, to teach. They did not impose, for wisdom imposed is wisdom lost. Instead, they offered a reflection—showing the world what it had forgotten about itself.

And slowly, the fragments began to come together.

Scholars saw the unity between their disciplines. Activists saw the patterns of history not as fate, but as wounds to be healed. Leaders saw that power need not be coercion, but could be self-regulation. People saw that the suffering of the world was not inevitable—but a choice made out of forgetting.

The mirror of reality, cracked for so long, began to clear.

The Fulfillment of the Restoration

There is no single moment when the world becomes whole again. Healing is not an event, but a process. Yet, with each person who awakens, with each fragment that finds its place, the world remembers a little more of itself.

The world is not lost. It is unfinished.

It was never meant to remain broken.

It was always meant to be restored.

And so, the work continues. The seeker walks forward, no longer alone.

For in the act of remembering, others begin to see.

In the act of integration, the world returns to itself.

All of the traditions and teachings discussed—Gnosticism, Taoism, Alchemy, Christian Mysticism, Hinduism, and even the insights of Buddha and Christ—share a fundamental principle: the quest for unity consciousness. This concept of unification, whether it’s the reconciliation of the soul with the divine in Christian Mysticism, the sacred marriage of opposites in Taoism and Alchemy, or the reuniting of Sophia with the divine source in Gnosticism, all point toward a deep, inherent truth: that division, suffering, and separation are illusions that hinder spiritual realization. Unity consciousness is the realization of oneness with the divine, where distinctions between the self and the greater whole dissolve, leading to transcendence.

This core concept ties deeply into both Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and Mirror Integration Theory (MIT). FCP, which explores how societal tensions and conflicts can ultimately lead to greater cohesion and understanding when approached with awareness and healing, mirrors the idea that apparent separation is a call for integration, a theme deeply embedded in all these spiritual teachings. MIT further complements this by suggesting that the way we heal internal fragmentation (such as the dualities within our psyche) is by integrating opposites—this concept directly connects to the reconciling of divine masculine and feminine, the integration of Yin and Yang, or the reunification of the soul with the source. Both FCP and MIT operate on the premise that healing and transformation occur through the recognition of wholeness, integrating opposing forces and dynamics to create a state of harmony. The journey to unity consciousness is the path that all of these teachings seek to guide individuals and societies toward, and it forms the common denominator that binds together both the mystical teachings and modern psychological frameworks. Ultimately, whether through spiritual teachings or psychological integration, unity consciousness represents the healing of division, the reconciliation of opposites, and the realization of the interconnectedness of all things.