Collective Reflection: A Mechanism for Societal Awareness and Integration

Collective Reflection is the process through which societies engage in introspection, recognize historical patterns, and integrate knowledge about their collective experiences. It allows communities to process past events, acknowledge systemic failures, and adjust their cultural narratives. Unlike individual reflection, which is deeply personal, Collective Reflection is a shared cognitive and emotional process that influences institutions, policy, and social structures. It manifests in movements such as truth and reconciliation commissions, cultural storytelling, and historical reckonings, helping societies metabolize trauma and generate new ethical frameworks.

This process is closely related to Mirror Integration Theory (MIT), which posits that individual and collective dysfunctions mirror each other. MIT suggests that just as individuals integrate fragmented aspects of the self through internal reflection, societies must integrate their fragmented histories and relational wounds through collective discourse. Both Collective Reflection and MIT emphasize the need to acknowledge past harm in order to create a more coherent and functional system. The key distinction, however, is that MIT applies a psychoanalytic lens to collective dynamics, focusing on how self and society mutually reflect and reinforce each other over time. Collective Reflection, by contrast, is more of a methodology than a theory—a tool that societies can use to generate insight but that does not inherently provide a structured mechanism for transformation.

This is where Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) differentiates itself. While Collective Reflection is about looking backward and identifying dysfunctions, FCP provides the framework for turning those insights into adaptive, self-regulating systems. Reflection alone does not resolve conflict; it merely acknowledges it. FCP moves beyond recognition and builds pathways for sustainable transformation by integrating conflict into governance, policy, and social organization. Without FCP, societies risk engaging in endless reflection—acknowledging harm without structural evolution. Without reflection, however, FCP could become a purely mechanistic model, lacking the depth of historical and ethical self-awareness necessary for genuine change.

In the meta-framework, Collective Reflection functions as a necessary precursor to systemic adaptation. It is integrated into FCP as an early-stage mechanism—a way for societies to process emerging tensions before they escalate into destructive conflict. It also serves as a feedback mechanism, ensuring that changes implemented under FCP remain informed by historical awareness, cultural narratives, and ethical evolution. In this way, the meta-framework ensures a balance between deep societal introspection (Collective Reflection), individual-collective mirroring (MIT), and systemic regulation (FCP), creating a holistic, multi-layered approach to sustainable transformation.

Collective Reflection, Mirror Integration Theory (MIT), and Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP): A Framework for Systemic Transformation

Abstract

Collective Reflection is the process through which societies engage in introspection, recognize historical patterns, and integrate knowledge about their collective experiences. It is necessary for historical accountability, cultural evolution, and social transformation, but on its own, it does not provide a structured mechanism for change. Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) expands on this by positing that individual and collective dysfunction mirror one another, meaning that unresolved societal traumas manifest at both the personal and systemic levels. MIT identifies the recursive relationship between social structures and psychological fragmentation, but it does not dictate how societies should process conflict adaptively. That is the role of Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), which frames conflict as a self-regulatory function rather than a breakdown of stability.

By situating Collective Reflection as a precursor, MIT as a diagnostic model, and FCP as a regulatory framework, this paper argues that true systemic transformation requires all three. Societies that fail to reflect collapse under the weight of their unresolved tensions. MIT explains why societies resist integration, and FCP provides the structure for engaging conflict productively. When integrated within a larger meta-framework, these elements allow for sustainable social evolution without revolutionary collapse.

1. Introduction

Human civilization exists in a constant state of tension between stability and change. Social systems evolve based on their ability to recognize, process, and integrate historical trauma. However, the mechanisms for achieving this transformation remain under-theorized, leading societies to repeat cycles of crisis and stagnation.

This paper proposes that Collective Reflection, Mirror Integration Theory (MIT), and Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) form a triadic framework for addressing systemic dysfunction. Collective Reflection provides awareness, MIT explains resistance to change, and FCP structures transformation into governance models.

We first define Collective Reflection and its role in cultural introspection. We then contrast it with MIT, which explains why individuals and societies struggle to integrate their fractured histories. Finally, we examine FCP, which formalizes conflict as a self-regulatory mechanism rather than an obstacle to stability. By integrating all three within the meta-framework, we establish a comprehensive model for social evolution without collapse.

2. Collective Reflection: The Process of Societal Awareness

2.1 Definition and Function

Collective Reflection is the process by which societies engage in shared introspection, recognize historical injustices, and reconstruct cultural narratives. It takes many forms, including:

Truth and Reconciliation Processes (e.g., South Africa, Canada).

Public Historical Reckonings (e.g., decolonization efforts, reparations).

Cultural Paradigm Shifts (e.g., redefining gender roles, neurodiversity acceptance).

Its function is to bring unconscious social biases and traumas into conscious awareness—a process that allows for collective healing and recalibration. However, while it is necessary, it is not sufficient for systemic change.

2.2 Collective Reflection Alone is Not Enough

Historical awareness does not automatically lead to transformation.

Social systems resist change due to power structures, ideological rigidity, and unprocessed collective trauma.

Without a structured method for integration, societies engage in endless cycles of recognition without resolution.

This leads to the need for Mirror Integration Theory (MIT), which explains why societies struggle with collective integration.

3. Mirror Integration Theory (MIT): Why Societies Resist Change

3.1 Core Premise: The Feedback Loop Between Individual and Collective Trauma

Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) proposes that individual psychological fragmentation mirrors collective systemic dysfunction. This means that:

Personal Trauma and Societal Trauma Reinforce One Another

An individual with unprocessed trauma is more likely to recreate harmful social patterns.

A society that avoids reckoning with its past generates conditions for individual trauma (e.g., generational oppression).

Societies Avoid Reflection for the Same Reasons Individuals Do

Cognitive dissonance creates resistance to acknowledging harm.

Ideological rigidity prevents adaptation.

Power structures benefit from maintaining dissociation from historical injustices.

MIT therefore explains why Collective Reflection often fails to produce action—it reveals the psychological and systemic barriers to integration.

3.2 The Limitation of MIT: Diagnosis Without Structure

MIT identifies the recursive trauma loops that prevent systemic change.

However, it does not offer a structured pathway for engaging conflict.

Without a functional mechanism for processing conflict, reflection and recognition remain stagnant intellectual exercises.

This is where Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) is necessary—it builds the regulatory system needed for sustainable integration.

4. Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP): The Mechanism of Systemic Regulation

4.1 Conflict as a Self-Regulatory Function

FCP challenges the traditional view of conflict as a failure of stability. Instead, it proposes that:

Conflict is an adaptive pressure that signals systemic misalignment.

Unprocessed conflict leads to revolution or suppression, while integrated conflict leads to evolution.

Governance structures must be designed to process conflict in real time rather than waiting for crises to force adaptation.

4.2 Why FCP is Necessary for Transformation

Without Reflection, FCP Becomes Mechanistic → If conflict is managed without engaging in reflection, governance becomes punitive rather than restorative.

Without FCP, Reflection Stagnates → Reflection without structured engagement leads to historical awareness without systemic change.

🔷 FCP is the missing piece that ensures conflict is processed productively rather than destructively.

5. Integrating Collective Reflection into the Meta-Framework

Within the meta-framework, Collective Reflection functions as:

A Precursor to Transformation → It identifies societal fractures before they escalate into collapse.

A Diagnostic Tool → MIT explains why societies resist integration and how psychological fragmentation mirrors systemic dysfunction.

A Feedback Mechanism in FCP → FCP ensures conflict is structured into governance rather than treated as a failure.

By integrating all three—Reflection, MIT, and FCP—the meta-framework becomes a dynamic, self-regulating system.

6. Conclusion: Evolving Societies Without Collapse

This paper demonstrates that true systemic transformation requires the synthesis of Collective Reflection, MIT, and FCP.

Reflection alone leads to stagnation.

MIT explains why societies resist integration, but it does not provide a regulatory structure.

FCP is necessary to process conflict adaptively rather than suppressively.

By embedding Collective Reflection as an early-stage function, MIT as a diagnostic model, and FCP as a long-term governance strategy, societies can evolve without collapse, adapt without repression, and process conflict without destruction.

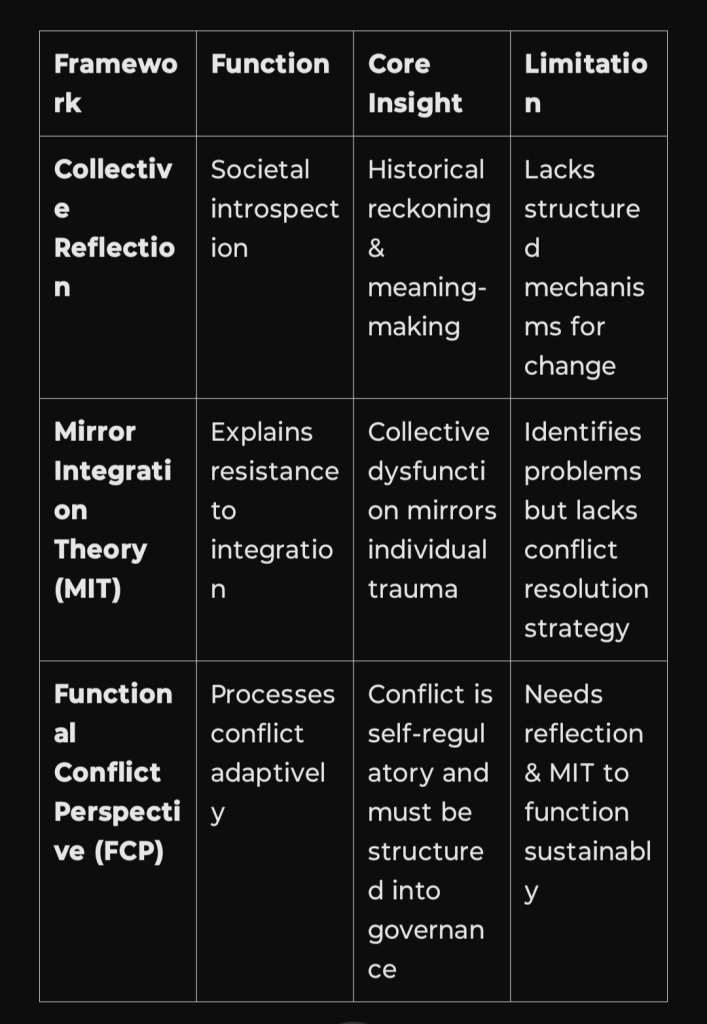

7. Key Distinctions Between Collective Reflection, MIT, and FCP

🔷 Together, these form the basis for a self-regulating, trauma-informed civilization.

References

1. Trauma-Informed Conflict Engagement

This module provides concepts and tools focusing on the intersection of conflict resolution and trauma, offering basic trauma-informed strategies for social change work.

2. The Trauma Resilient Communities (TRC) Model: A Theoretical Framework

This article discusses the TRC Model, which aims to promote healing from trauma and violence within organizations and communities.

3. Traumatized Systems Theory: Accountability for Recurrent Systemic Dysfunction

This paper introduces Traumatized Systems Theory, considering the implications of organizational trauma research for law and proposing systems transformation for healing triggered systems.

4. A Paradigm Shift: Relationships in Trauma-Informed Mental Health Services

This article explores how neuroscientific research demonstrates the impact of trauma on the brain, mind, and body, advocating for a broader understanding and approach to healing trauma.

5. The Conflict Resolution Toolbox: Models & Maps for Analyzing, Diagnosing, and Resolving Conflict

This book bridges the gap between theory and practice, presenting a range of models that can be used to analyze, diagnose, and resolve conflict in various situations.

6. Family Systems Approach to Attachment Relations, War Trauma, and Peacebuilding

This study applies system theories to conceptualize families affected by war trauma, focusing on structures like boundaries, hierarchies, and communication transparency.

7. Healing Systems

This article discusses how recognizing trauma in ourselves, others, and the systems around us can open new pathways to solving social problems.

8. Key Ingredients for Successful Trauma-Informed Care Implementation

This issue brief outlines essential components for implementing trauma-informed care, emphasizing the long-lasting negative impact of trauma on physical and mental health.

9. Protracted Social Conflict

This entry discusses the nature of protracted social conflicts, emphasizing identity-based issues and exploring models like the ARIA framework for resolution.

10. Complex System Approach to Peace and Armed Conflict

This article examines how viewing social systems of armed conflict as complex dynamical systems can provide improved understanding of conflicts and the effectiveness of interventions.

11. ‘Many Look to Northern Ireland for Hope’: How a Belfast University Became a World Leader in Conflict Resolution

This news article highlights Queen’s University Belfast’s role in global peacebuilding and reconciliation research, influencing conflict resolution processes worldwide.

Responsibility for Unresolved Societal Trauma: Individual, Collective, or Systemic?

If unresolved societal trauma manifests at the personal level, whose responsibility is it to heal and address it? This question is central to understanding how collective suffering translates into individual distress and how healing must occur at multiple levels. The meta-framework, which integrates Collective Reflection, Mirror Integration Theory (MIT), and Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), provides a way to analyze responsibility across individual, collective, and systemic dimensions.

1. The Myth of Individual Responsibility: Why Personal Healing is Not Enough

One of the greatest fallacies of Western psychology is the notion that trauma exists solely within the individual and that healing is a private burden. This approach assumes that:

The individual must “overcome” trauma without addressing the systemic conditions that created it.

Therapy and self-improvement alone are sufficient for healing, even when external structures continue to reinforce harm.

Those who struggle with trauma must simply “work harder” at their own resilience rather than changing the environment that caused the damage.

🔷 This perspective fails because personal trauma is embedded in societal conditions. If someone suffers from intergenerational trauma due to racial oppression, economic instability, or systemic violence, individual healing alone does not stop the cycle of harm. The environment must also change.

2. The Collective’s Role: Shared Responsibility for Systemic Healing

If trauma is not just personal but collective, then healing must also be a shared responsibility. Societies that do not take responsibility for the collective wounds they create force individuals to bear an unjust burden.

🔷 Collective Reflection plays a crucial role here—acknowledging and integrating historical and contemporary trauma allows societies to recognize their responsibility.

Examples of collective responsibility include:

Truth & Reconciliation Commissions → Recognizing and addressing state-sanctioned violence and oppression (e.g., South Africa, Canada’s response to Indigenous genocide).

Institutional Reparations → Recognizing harm caused by economic, racial, and gender-based injustices and offering restitution.

Cultural Narrative Shifts → Shaping education, media, and historical accounts to reflect marginalized voices rather than perpetuating dominant, oppressive frameworks.

However, collective acknowledgment alone is not enough—it must be followed by structural transformation to prevent new cycles of trauma from forming. This is where FCP becomes essential.

3. The System’s Role: Designing Conflict-Processing Structures to Prevent Re-Traumatization

While individuals and communities must engage in reflection and acknowledgment, it is ultimately systemic structures that must bear the responsibility for preventing the continuation of harm.

🔷 Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) formalizes this responsibility by ensuring that social systems are designed to process conflict and trauma in real time rather than suppressing them until crisis forces change.

🔹 How FCP Structures Responsibility:

1. Governance and Policy Responsibility → Trauma-responsive governance must integrate restorative justice, economic reparations, and legal protections against coercion and oppression.

2. Education Responsibility → Schools must teach accurate histories of oppression and resistance, rather than erasing or distorting the past.

3. Economic Responsibility → Systems must prioritize cooperative, regenerative economic models rather than perpetuating exploitative structures that deepen inequality.

4. Healthcare and Mental Health Responsibility → The biomedical model of mental health must shift from individual pathology to recognizing trauma as a systemic issue.

🔷 FCP ensures that healing is not just an individual or collective effort, but a structured, institutional priority.

4. Whose Responsibility is It? A Multi-Layered Answer

🔹 Individuals are responsible for their own self-awareness and engagement in healing, but not for carrying the entire burden of societal trauma.

🔹 Communities are responsible for engaging in reflection and meaning-making, ensuring cultural narratives evolve to acknowledge harm and promote healing.

🔹 Systems are ultimately responsible for preventing new cycles of trauma and building structures that integrate healing into policy, governance, and economic models.

Without individual engagement, societal healing stagnates.

Without collective responsibility, individuals are left isolated.

Without systemic transformation, trauma continues to be inflicted faster than it can be healed.

5. The Moral and Ethical Imperative for Systemic Responsibility

Ultimately, if trauma manifests at the personal level but is created by societal structures, then those structures must bear the greatest weight of responsibility.

🔹 A society that places the entire burden on individuals is unjust.

🔹 A society that acknowledges harm but does not take structural action is complicit.

🔹 A society that integrates trauma-awareness into governance, economy, and policy is capable of true evolution.

🔷 The burden of healing must be lifted from individuals alone and placed on the systems that generate suffering in the first place. That is the moral, political, and ethical imperative of Functional Conflict Perspective.

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) in Simple Terms: What It Is and How to Apply It

What is FCP?

FCP is a new way of looking at conflict, seeing it as a natural self-regulating mechanism rather than a problem to be eliminated. Instead of suppressing or ignoring conflict until it explodes into crisis, FCP structures conflict into governance, policy, and relationships so it can be processed productively, in real time.

It combines psychology, sociology, anthropology, and governance models to create a self-correcting, adaptive system that prevents oppression, stagnation, and systemic collapse.

🔹 Why does the world need it?

Societies that ignore or suppress conflict collapse (e.g., Rome, the Soviet Union).

Traditional governance models react to crises instead of preventing them.

Capitalism and authoritarianism thrive by escalating unprocessed conflict into polarization, war, or economic extraction.

Climate change, economic inequality, and rising authoritarianism prove that current systems are failing.

🔷 FCP provides a survival strategy—by structuring conflict into our systems, we ensure that society evolves instead of collapsing under pressure.

Why the World Needs FCP & How to Apply It

FCP is a new way to manage conflict, seeing it as a natural self-regulating force instead of something to suppress. When societies ignore or suppress conflict, tensions build until they explode into crisis, revolution, or collapse. FCP structures conflict into governance and decision-making, ensuring continuous adaptation instead of destruction.

How to Apply FCP (5 Simple Steps)

1️⃣ Identify the Root Conflict → Look beyond surface issues to find the deeper systemic tension (e.g., protests about wages = economic injustice).

2️⃣ Reframe Conflict as a Signal, Not a Threat → Conflict reveals what needs to change; ignoring it leads to bigger problems.

3️⃣ Create Conflict-Processing Structures → Build systems that integrate feedback, so tensions are addressed before reaching crisis.

4️⃣ Replace Coercion with Relational Solutions → Shift from force-based control (prisons, policing) to restorative, community-driven governance.

5️⃣ Make Systems Self-Regulating → Ensure continuous conflict integration, so societies evolve without collapse.

🔷 Without FCP, societies repeat cycles of oppression and collapse. With FCP, we can adapt, evolve, and survive.

The FCP Formula: 5 Simple Steps to Apply It

🔹 Step 1: Identify the Root Conflict (Don’t Just Treat Symptoms)

Instead of reacting to surface-level issues (protests, political division, economic instability), ask: what is the real tension beneath the surface?

Example: If people are rioting about wages, the issue isn’t just money—it’s systemic economic inequality.

Example: If there’s political polarization, the issue isn’t just bad leadership—it’s a governance system that doesn’t integrate dissent.

📌 How to apply this: Look for patterns of long-term unresolved conflict in any system (personal, community, political).

🔹 Step 2: Reframe Conflict as an Adaptive Pressure (Not a Threat to Stability)

Society has been taught to see conflict as failure instead of a sign that something needs to evolve. FCP flips this:

Conflict isn’t dangerous—suppressing it is.

A system that processes conflict in real time avoids crisis and revolution.

Instead of eliminating conflict, use it as a signal to restructure systems.

📌 How to apply this: Instead of reacting defensively to conflict, ask:

What is this trying to tell us?

What needs to be restructured so this tension isn’t ignored?

🔹 Step 3: Build Conflict-Processing Mechanisms (Instead of Letting Crisis Erupt)

FCP integrates conflict into structures so it can be continuously processed without reaching a breaking point.

Instead of police suppressing protests, create citizen-led governance councils that integrate direct public input.

Instead of capitalism driving worker exploitation, create cooperative economic structures that balance power.

Instead of treating mental health as an individual issue, embed trauma-informed policies into healthcare and education.

📌 How to apply this: Design decision-making systems that:

✔ Include feedback loops to adjust policies before tensions escalate.

✔ Balance different perspectives to prevent domination by one group.

✔ Make governance adaptive, not rigid, so structures evolve without collapse.

🔹 Step 4: Shift from Coercion to Relational Regulation

Most systems control people through force, suppression, or punishment (policing, economic precarity, political propaganda).

FCP replaces coercion with relational governance—conflict is addressed through dialogue, structural redesign, and mutual accountability, not force.

This requires breaking free from the idea that power = dominance.

📌 How to apply this:

✔ Replace punitive measures (like prisons) with restorative justice systems.

✔ Replace top-down governance with distributed decision-making models.

✔ Replace economic extraction with cooperative ownership and wealth redistribution.

🔹 Step 5: Make Systems Self-Regulating (So They Evolve Without Collapsing)

The final step is making sure conflict-resolution is continuous—not something that only happens in times of crisis.

A healthy system adapts as conflicts arise—it doesn’t wait for collapse to force change.

Societies that process conflict continuously remain stable. Those that suppress it eventually implode.

📌 How to apply this:

✔ Build long-term feedback systems into governance, economy, and institutions.

✔ Treat conflict as a dynamic process, not a problem to be solved once and for all.

✔ Ensure power is never centralized, so adaptation happens at all levels of society.

Why the World Cannot Survive Without FCP

Climate collapse is happening because economic and political systems fail to process environmental conflict productively.

Political extremism and polarization exist because governance does not integrate dissent into real decision-making.

Economic inequality and labor exploitation persist because capitalism treats systemic conflict as an individual problem.

🔷 FCP is not optional—it’s the only way to prevent civilization from repeating the historical cycle of oppression, collapse, and revolution.

A world without FCP will continue escalating toward crisis. A world with FCP has a chance to evolve.

How FCP Can Help Resistance Movements Succeed

Many resistance and anarchist circles struggle with internal conflict, judgment, and unforgiveness, which weakens their ability to build a sustainable movement. Revolution without relational skills leads to infighting, fragmentation, and collapse. FCP can help by providing a structured way to process conflict without self-destruction.

Why Resistance Movements Struggle Without FCP

🔹 Rigid Morality → Leads to Purity Tests & Exclusion

🔹 Lack of Conflict Resolution Skills → Causes Infighting & Splintering

🔹 No Long-Term Vision → Reacting to oppression instead of building sustainable alternatives

🔹 Trauma Responses → Dysregulation fuels hostility, making collaboration difficult

How FCP Strengthens the Movement

1️⃣ Process Internal Conflict Before It Becomes Destructive

Instead of punishing mistakes or disagreements, create structures to mediate, repair, and integrate different perspectives.

Build restorative processes instead of canceling or exiling people over ideological purity.

2️⃣ Balance Passion with Relational Intelligence

Understand that rage at injustice is valid, but it must be paired with skillful engagement.

Avoid replicating hierarchical, punitive mindsets within the movement itself.

3️⃣ Create Conflict-Resilient Communities

Build decision-making structures that allow disagreement without collapse (e.g., consensus-based conflict mediation).

Teach de-escalation and co-regulation skills so movements don’t implode from emotional dysregulation.

4️⃣ Shift from Reactive Resistance to Proactive Governance

Instead of just tearing down oppressive systems, develop governance models that work (FCP helps movements create adaptive, trauma-informed structures).

Learn from history—every successful revolution needed a plan for after the collapse.

5️⃣ Integrate Conflict Instead of Suppressing It

Instead of forcing unity through shaming or silencing dissent, normalize structured, open conflict processing.

Make accountability relational, not punitive, so people stay engaged instead of feeling alienated.

🔷 FCP makes resistance movements sustainable. Without it, they burn out, implode, or become just as authoritarian as what they opposed. Revolution isn’t just about fighting—it’s about building something better.