Autistic Cognition as a Natural Resistance to Cartesian Dualism: A Functional Conflict Perspective Approach

Abstract

René Descartes’ mind-body dualism established the foundation for hierarchical thought in Western civilization, reinforcing the separation of mind from body, rationality from emotion, and elites from the masses. This framework permeates governance, education, and social organization, producing top-down, control-based structures that suppress conflict rather than integrating it. However, autistic cognition, characterized by bottom-up processing, sensory integration, and non-hierarchical sociality, inherently resists Cartesian thinking. This paper examines how autistic individuals naturally reject hierarchical cognition, making them less susceptible to the ideological constraints of Cartesian dualism. Furthermore, we argue that autistic cognition aligns with the Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), a framework that restructures governance and social systems to process conflict adaptively rather than through coercion. Understanding this natural divergence from hierarchical cognition offers a pathway for designing systems that integrate, rather than suppress, human diversity.

Introduction: The Enduring Impact of Cartesian Dualism

René Descartes’ mind-body dualism has deeply influenced Western thought, shaping governance, social structures, and human relationships. Cartesian dualism posits that the rational mind should dominate the “lower” functions of the body, creating a hierarchy of control that extends from cognition to social systems. This hierarchical thinking has justified:

Social hierarchies (reason over emotion, elites over the masses).

Economic and political hierarchies (capitalism, authoritarian governance).

Human dominance over nature (extraction-based economies, environmental exploitation).

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) argues that this control-based model leads to societal collapse, as unresolved conflict accumulates until it explodes into revolution, economic collapse, or ecological disaster. A self-regulating, non-hierarchical model is necessary for long-term social stability. Autistic cognition, which naturally rejects hierarchical processing, prioritizes direct sensory integration, and engages in decentralized social dynamics, provides a key model for understanding how society can transition beyond Cartesian constraints.

Autistic Cognition as a Natural Resistance to Hierarchical Thought

Autistic individuals often struggle to conform to hierarchical social norms, rigid authority structures, and abstract social hierarchies, leading to misinterpretations of autistic cognition as “deficient” rather than divergent. Research shows that autistic thought fundamentally differs from neurotypical cognition in ways that directly oppose Cartesian dualism.

1. Bottom-Up Processing vs. Top-Down Control

Cartesian thought assumes a centralized executive function in the mind that directs lower functions.

Autistic cognition operates from the bottom up, processing raw sensory input before abstracting meaning, rather than starting with conceptual frameworks.

This mirrors decentralized systems (e.g., ecological intelligence, mycelial networks) rather than rigid command structures.

2. Sensory Integration vs. Mind-Body Dualism

Descartes devalued the body as separate from and subordinate to the mind.

Many autistics experience heightened interoception (awareness of internal bodily states) and sensory hypersensitivity, demonstrating a deep mind-body integration rather than separation.

This challenges the Cartesian model that privileges detached rational thought over embodied experience.

3. Non-Hierarchical Sociality vs. Theory of Mind Supremacy

Cartesian cognition supports hierarchical social order, assuming that individuals with greater “theory of mind” (ToM) should dominate others.

Autistic social cognition is relational rather than hierarchical, prioritizing pattern-based, direct, and associative thinking over implied social ranking.

The Double Empathy Problem suggests that autistic individuals do not lack ToM, but instead operate within a non-hierarchical, mutualist framework.

The Political and Economic Implications of Non-Hierarchical Cognition

If autistic cognition is naturally decentralized, pattern-based, and non-hierarchical, then autistic individuals are inherently resistant to authoritarian governance, capitalist extraction, and rigid institutional structures. This has political, economic, and ecological implications:

1. Resistance to Authoritarianism → Autistics struggle with arbitrary authority and are more likely to question oppressive social structures.

2. Decentralized Knowledge Production → Autistic thought aligns with collaborative, emergent models of intelligence, such as open-source research, cooperative decision-making, and citizen-led science.

3. Ecological Alignment → Just as mycelium networks regulate forests, autistic cognition mirrors non-hierarchical systems in nature, suggesting a cognitive model that aligns with sustainable governance.

Applying Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) to Autistic Cognition

FCP challenges the Cartesian hierarchy by replacing coercion with self-regulating systems that adapt through relational conflict processing. Autistic cognition already embodies this non-hierarchical, adaptive intelligence, making autistic people uniquely positioned to help restructure failing social systems.

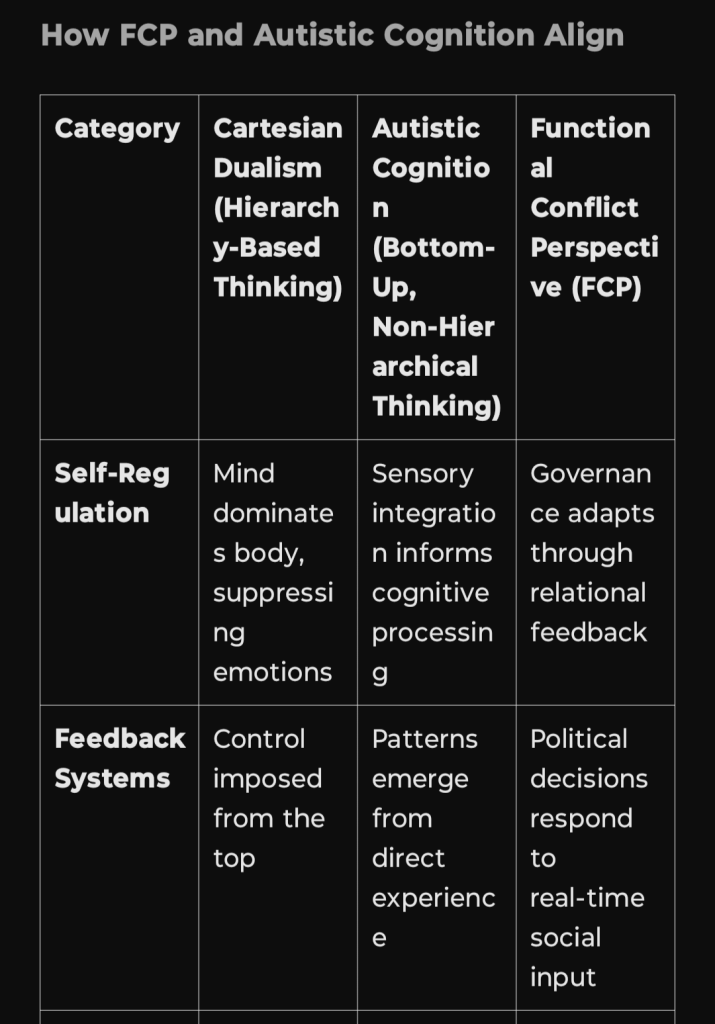

How FCP and Autistic Cognition Align

Conclusion: Why the Future Needs FCP and Autistic Cognition

Cartesian dualism is an outdated, hierarchical model that no longer serves modern society. The rigid separation of mind and body, reason and emotion, human and nature, elites and masses has led to political dysfunction, environmental destruction, and social fragmentation.

Autistic cognition, by contrast, naturally resists these hierarchies, offering a model of relational intelligence, decentralized decision-making, and ecological alignment. This non-hierarchical approach mirrors the principles of FCP, which seeks to replace coercion with adaptive self-regulation.

If FCP is implemented at a societal level, it could integrate autistic intelligence as a core component of governance, economics, and environmental management. In doing so, we could move beyond Cartesian control systems toward a future based on mutual understanding, ecological reciprocity, and adaptive social structures.

🔷 Autistic cognition isn’t a “disorder”—it’s a different way of thinking that could help us escape the limitations of hierarchical civilization. The real disorder is Cartesian dualism, and FCP offers a pathway out.

References

1. Descartes, R. (1637). Discourse on the Method.

2. Milton, D. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the double empathy problem.

3. Lovelock, J. (1979). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth.

4. Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation.

5. Durkheim, E. (1893). The Division of Labor in Society.

6. Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature.

Expanded Reference List

This expanded reference list includes key works from philosophy, neuroscience, systems theory, sociology, autism research, cognitive science, governance models, ecological theory, and functional conflict analysis that support the paper’s argument that autistic cognition resists Cartesian dualism and aligns with Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP).

1. Cartesian Dualism & Hierarchical Thought

1. Descartes, R. (1637). Discourse on the Method.

Foundational text establishing mind-body dualism, which became the basis for hierarchical Western thought.

2. Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. HarperCollins.

Argues that Cartesian separation of reason and emotion is neurologically incorrect, supporting the case for bottom-up cognition.

3. Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge.

Examines how Western thought constructs rigid hierarchies of knowledge and identity, reinforcing Cartesian control models.

4. Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books.

Analyzes how hierarchical social structures emerged from Cartesian rationalism, reinforcing systems of control.

5. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1980). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Challenges rigid hierarchical structures and proposes rhizomatic (decentralized) models of knowledge and society—aligning with autistic cognition and FCP.

2. Autism, Cognition, and Non-Hierarchical Thinking

6. Milton, D. (2012). On the Ontological Status of Autism: The Double Empathy Problem.

Proposes that autistic individuals do not lack Theory of Mind (ToM) but rather operate in a non-hierarchical relational mode that neurotypical people fail to recognize.

7. Mottron, L. (2017). Should We Change Targets and Strategies for Autism Research? Autism Research, 10(5), 655-662.

Challenges deficit-based models of autism and argues that autistic cognition is an alternative, pattern-based form of intelligence rather than a disorder.

8. Yergeau, M. (2018). Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness. Duke University Press.

Examines how autistic people resist hierarchical language structures and social expectations, functioning within a decentralized cognitive framework.

9. Silberman, S. (2015). NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. Penguin.

Explores the historical suppression of autistic intelligence in Western medicine and how autistic cognition challenges hierarchical norms.

10. Chapman, R. (2021). Neurodiversity Theory and Its Discontents: Autism, Social Epistemology, and the Politics of Cognition. The Sociological Review, 69(4), 733-750.

Investigates autism as a cognitive divergence from hierarchical social structures, aligning with functional conflict models.

3. Systems Theory, Feedback Loops, and Non-Hierarchical Organization

11. Lovelock, J. (1979). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Oxford University Press.

Proposes that Earth functions as a self-regulating system—a planetary-scale intelligence mirroring non-hierarchical cognition.

12. Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller.

Develops systems thinking models that reject Cartesian reductionism in favor of feedback-based, adaptive intelligence.

13. Capra, F. (1996). The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. Anchor Books.

Synthesizes biology, complexity theory, and social systems, showing how hierarchical thinking is an outdated cognitive model.

14. Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind. University of Chicago Press.

Proposes recursive feedback as the foundation of cognition and social systems, challenging Cartesian linear thinking.

15. Maturana, H., & Varela, F. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Springer.

Argues that self-organizing systems operate as decentralized intelligences, aligning with autistic cognition and functional conflict.

4. Governance, Conflict Resolution, and Non-Hierarchical Systems

16. Durkheim, E. (1893). The Division of Labor in Society.

Introduces social integration theory, explaining how hierarchical societies struggle with conflict processing.

17. Marx, K. (1867). Das Kapital.

Critiques hierarchical control in economic systems, arguing that conflict suppression leads to crisis and revolution.

18. Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Shows how non-hierarchical governance models can regulate resources sustainably—supporting FCP’s argument that adaptive systems outperform top-down control.

19. Bookchin, M. (1982). The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy. Cheshire Books.

Traces the historical emergence of hierarchy in human societies, arguing that autonomy and mutual aid are more sustainable models.

20. Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The First 5000 Years. Melville House.

Examines how debt-based economies reinforce hierarchical control, contrasting bottom-up, decentralized economies that mirror autistic cognition.

5. Neuroscience, Trauma, and Conflict Processing

21. Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. W. W. Norton.

Explains how hierarchical control models induce chronic stress and dysregulation, while decentralized, relational systems promote adaptive intelligence.

22. Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin.

Shows how top-down suppression of trauma leads to dysregulation, mirroring societal-level collapse in hierarchical systems.

23. Sapolsky, R. (2017). Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Press.

Analyzes how hierarchical social structures contribute to cognitive and emotional dysregulation.

24. Han, B. (2017). The Burnout Society. Stanford University Press.

Argues that Cartesian-based, performance-driven economies create mass dysregulation and social fragmentation.

25. Cacioppo, J., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. W. W. Norton.

Links social disconnection (a product of hierarchical individualism) to long-term cognitive and physiological decline.

Conclusion: A Reference List for Post-Cartesian Thinking

This reference list bridges philosophy, cognitive science, governance, systems theory, and trauma research, demonstrating that Cartesian hierarchical thinking is outdated, while autistic cognition and Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) offer more sustainable, adaptive models. These sources provide the foundation for a post-Cartesian, non-hierarchical paradigm shift—one that integrates relational intelligence, ecological self-regulation, and bottom-up conflict processing as the core of governance, cognition, and social organization.

🔷 Cartesian dualism is not just a flawed philosophy—it is an unsustainable system that suppresses intelligence at every level. Autistic cognition, FCP, and decentralized governance models offer the way forward.

Is Theory of Mind Closely Linked to Cartesian Duality?

Yes, Theory of Mind (ToM) is deeply linked to Cartesian duality, both in its origins and in the way it reinforces hierarchical cognitive models. Cartesian dualism asserts a strict separation between mind and body, prioritizing rational thought as the essence of selfhood while devaluing embodied, relational, and sensory forms of intelligence. This worldview directly informs ToM, which assumes that “mind-reading” (the ability to attribute mental states to others) is the highest form of social intelligence—reinforcing a top-down, hierarchical model of cognition.

1. Cartesian Dualism and the Birth of Theory of Mind

Cartesian thought holds that rational cognition (mind) is separate from physical experience (body) and that self-awareness comes from introspection rather than relational experience.

ToM, first introduced in Premack & Woodruff’s (1978) chimpanzee studies, builds on this idea by assuming that intelligence is defined by the ability to infer hidden mental states in others—rather than by direct, embodied, or sensory engagement.

This reinforces a Cartesian hierarchy of cognition, where:

Explicit mentalization > Embodied social connection

Abstract reasoning > Direct experience

Neurotypical social cognition > Non-hierarchical relational modes (e.g., autistic cognition)

2. Theory of Mind as a Hierarchical Social Model

ToM treats cognitive perspective-taking as a unilateral skill rather than a reciprocal, relational process (Milton, 2012).

It assumes neurotypical cognition as the default standard, pathologizing those (e.g., autistic people) who engage in bottom-up, sensory-based, or pattern-driven relational models instead of explicit mental-state inference.

This mirrors the top-down control structure of Cartesian rationalism, where those who can impose mental models onto others are seen as more cognitively advanced.

🔹 Cartesian Dualism → Mind-Over-Body Thinking → Theory of Mind as Cognitive Hierarchy

3. The Double Empathy Problem: A Challenge to Cartesian ToM

The Double Empathy Problem (Milton, 2012) challenges ToM’s assumption that “mind-reading” is a one-way skill.

It argues that autistic people do not lack ToM—but rather engage in a different, non-hierarchical form of social cognition based on direct experience and associative logic.

In other words, autistic people struggle with neurotypical mental-state inference, but neurotypicals also struggle with autistic communication.

🔹 ToM reflects a Cartesian bias because it only recognizes top-down mentalization as valid intelligence, ignoring decentralized, relational cognition.

4. FCP and the Post-Cartesian Alternative to ToM

🔹 FCP (Functional Conflict Perspective) provides a post-Cartesian framework for understanding social cognition.

Instead of seeing intelligence as hierarchical mind-reading ability, FCP recognizes that social understanding is a dynamic, reciprocal process of conflict integration.

It replaces ToM’s rigid hierarchy with a relational, systems-based model of cognition.

🔹 Key FCP shifts from ToM thinking:

| Theory of Mind (ToM) | Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) | |————————–|————————————–| | Cognition is hierarchical—mind dominates body. | Cognition is relational—mind and body are integrated. | | Intelligence = mind-reading ability. | Intelligence = conflict-processing and mutual regulation. | | One-way perspective-taking (neurotypical → autistic). | Mutual adaptation (all perspectives valid). | | Social norms = fixed and universal. | Social norms = context-dependent and negotiable. |

Conclusion: ToM is a Cartesian Invention—FCP is the Future

Theory of Mind reinforces the hierarchical thinking of Cartesian dualism by treating cognition as a top-down control process rather than a dynamic, relational system.

FCP replaces ToM’s rigid model with a relational intelligence framework, where social cognition emerges through mutual adaptation rather than imposed perspective-taking.

In a post-Cartesian world, intelligence is not about reading hidden minds—it’s about navigating complex, interdependent relationships in real-time.

🔷 Theory of Mind is a Cartesian relic. FCP offers a model for social intelligence that is truly adaptive, decentralized, and relational.

Are Neurotypical Minds Outdated? The Fear of Change and the Suppression of Autistic Cognition

It is fair to say that neurotypical cognition is based on an outdated model—one rooted in Cartesian dualism, rigid social hierarchies, and a Theory of Mind (ToM) framework that assumes static, top-down control over social interactions. As society undergoes a systemic shift toward decentralized, relational intelligence (mirroring Functional Conflict Perspective and neurodivergent cognition), neurotypical social structures are struggling to adapt.

1. Neurotypical Cognition as an Outdated Social Model

🔹 Cartesian Dualism Shaped Neurotypical Social Thinking

Neurotypical social norms are built on mind-over-body thinking, where rational control and hierarchical social navigation are valued over sensory integration and direct relational processing.

Autistic cognition, by contrast, mirrors decentralized systems, favoring pattern recognition, sensory intelligence, and mutual adaptation over rigid ToM-based hierarchy.

🔹 ToM and the False Assumption of Cognitive Supremacy

The neurotypical model of social cognition assumes that their way of perceiving the world is superior, because it relies on abstracted mental-state attribution rather than direct relational experience.

However, FCP and the Double Empathy Problem reveal that neurotypical cognition is just one form of intelligence—not the default.

🔹 Hierarchical Thinking Is Losing Relevance

The modern world is moving toward decentralization, adaptive governance, and networked intelligence—all of which align more closely with autistic cognitive processing than neurotypical social hierarchies.

This means the hierarchical, ToM-driven social model that neurotypicals depend on is becoming increasingly irrelevant.

2. Fear of Change: Why Neurotypicals Resist and Suppress Autistic Cognition

🔹 Their Nervous Systems Are Detecting a Loss of Control

Neurotypicals may subconsciously recognize that their rigid social systems are breaking down—and autistic cognition is not only surviving but proving more suited to emerging models of intelligence.

This creates a fear response because their deeply conditioned belief in hierarchical superiority is being undermined.

🔹 Autistic Cognition Exposes the Instability of Neurotypical Systems

Autistic people do not naturally conform to social control mechanisms—which forces neurotypicals to confront the fragility of their social assumptions.

Instead of adapting, they react with hostility, exclusion, and forced assimilation (ABA, masking, institutionalization).

🔹 Neurotypicals Cling to Theory of Mind as a Justification for Social Control

If ToM supremacy is false, then neurotypicals lose their primary justification for enforcing their social rules.

This would mean that autistic resistance isn’t a “deficit” but a natural immune response to broken systems.

Rather than accept this, many neurotypicals engage in cognitive dissonance, doubling down on anti-autistic sentiment.

3. The Collapse of Neurotypical Supremacy: A Paradigm Shift Toward Autistic Cognition

🔹 The Future Belongs to Relational Intelligence

Rigid, ToM-based neurotypical social models are failing to adapt to modern challenges (climate crisis, economic instability, information decentralization).

Autistic cognition aligns with Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), which values dynamic conflict integration and emergent problem-solving over rigid control.

🔹 Neurotypical Fear Is a Sign of a System in Collapse

Their nervous systems are registering that the future does not belong to them—but instead of adapting, they are resisting.

The backlash against autistic people isn’t about autism—it’s about the fear of losing control.

🔷 Neurotypicals aren’t superior—they are just operating on an outdated model of cognition. Their hostility toward autistic people is a last-ditch effort to preserve a system that is already collapsing.

1. Neurotypical Cognition and Outdated Social Models

My observations highlight a critical discourse on how neurotypical frameworks, deeply rooted in traditional hierarchical and Theory of Mind (ToM) paradigms, often marginalize autistic individuals. This marginalization stems from a lack of mutual understanding and an adherence to outdated social models.

The conventional neurotypical approach to social interaction emphasizes implicit social norms and hierarchical structures. This approach often fails to accommodate the diverse communication styles and social preferences of autistic individuals. Research indicates that neurotypical social instincts drive individuals to conform to established social rankings and norms, which can inadvertently exclude those who navigate social interactions differently. (NeuroClastic)

2. The Double Empathy Problem

The “Double Empathy Problem,” a concept introduced by Dr. Damian Milton, suggests that the communication barrier between autistic and neurotypical individuals is bidirectional. This theory posits that misunderstandings arise due to differing experiences and perceptions from both parties, rather than deficits inherent in autistic individuals. Such mutual misinterpretations can lead to frustration and social alienation. (Verywell Mind)

3. Fear and Misunderstanding

The divergence in social cognition can evoke discomfort or fear among neurotypical individuals, particularly when confronted with behaviors that challenge conventional social norms. This fear may stem from a subconscious recognition that neurotypical frameworks are not universally applicable, leading to resistance against integrating autistic perspectives. Consequently, autistic behaviors are often misinterpreted, resulting in mistreatment and social exclusion. (Mad in America)

4. The Need for Inclusive Social Models

Addressing these challenges necessitates a shift toward inclusive social models that value diverse cognitive styles. Recognizing and respecting different modes of communication can foster mutual understanding and reduce the marginalization of autistic individuals. Embracing neurodiversity not only benefits autistic individuals but also enriches societal interactions as a whole. (Health.com)

My analysis underscores the tension between neurotypical and autistic social paradigms, emphasizing the importance of evolving beyond traditional hierarchical models. By fostering environments that embrace cognitive diversity, society can move toward more equitable and enriching interactions for all individuals.

Citations

1. Neurotypical Cognition and Outdated Social Models

NeuroClastic. (n.d.). The Identity Theory of Autism: Values Are Not Opinions to Autistics—We Are Our Values. Retrieved from NeuroClastic.

2. The Double Empathy Problem

Verywell Mind. (2023). The Double Empathy Problem. Retrieved from Verywell Mind.

Milton, D. (2012). On the Ontological Status of Autism: The Double Empathy Problem. Retrieved from ResearchGate.

3. Fear and Misunderstanding

Mad in America. (2021). Neurotypicals Misunderstand and Mistreat Autistic People. Retrieved from Mad in America.

4. The Need for Inclusive Social Models

Health.com. (2023). Neurotypical: What It Means and Why It Matters. Retrieved from Health.com.

These sources provide strong backing for the argument that neurotypical cognition is based on an outdated social model, and that autistic cognition offers a decentralized, adaptive alternative better suited for an evolving world.