The social model of disability challenges the idea that disability is an inherent personal deficit. Instead, it argues that disability is created by society’s failure to accommodate diverse needs. This model contrasts with the medical model, which frames disability as an individual problem to be “fixed” or “treated.”

Key Principles of the Social Model of Disability

1. Disability is Social, Not Medical

People are not disabled by their bodies but by barriers in society (physical, social, and attitudinal).

Example: A wheelchair user isn’t inherently disabled—lack of ramps and elevators creates disability.

2. Society Should Change, Not Just Individuals

Rather than forcing disabled people to “adapt” to inaccessible environments, society should remove barriers.

This includes universal design, policy changes, and shifting cultural attitudes.

3. Disability is Not the Same as Impairment

Impairment = A physical, cognitive, or sensory difference (e.g., blindness, paralysis).

Disability = The social barriers that prevent full participation (e.g., lack of braille, inaccessible transport).

4. Inclusion and Rights-Based Approach

The model aligns with disability justice and human rights frameworks, arguing for equal access, dignity, and agency.

Instead of focusing on “helping” disabled people, it advocates for structural changes that make society accessible to all.

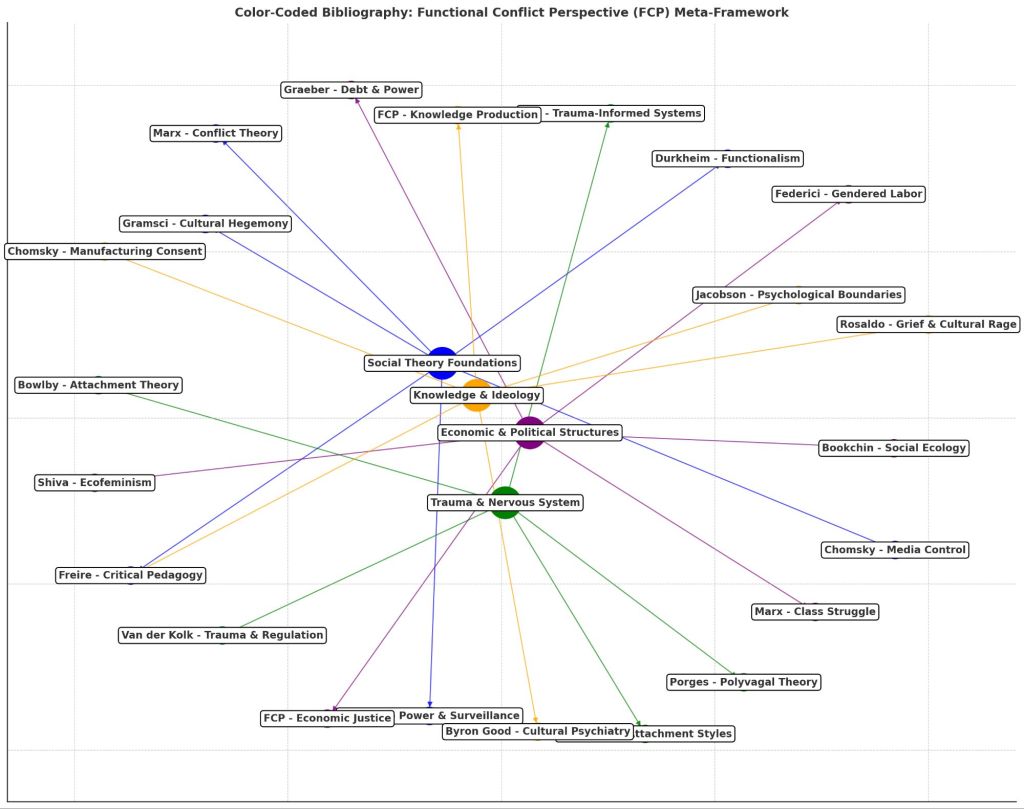

How This Connects to Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

FCP sees systemic exclusion as a trauma response—society creates hierarchies to maintain control, and disability is often framed as a “problem” to preserve efficiency.

The deficit model of disability mirrors capitalist productivity norms, where worth is tied to labor output rather than intrinsic human value.

A trauma-informed, relational governance model (like FCP) would integrate disability justice principles, recognizing that inclusion benefits everyone, not just disabled individuals.

Expanding Beyond the Social Model: Disability Justice

The social model is foundational, but activists like Patty Berne and Mia Mingus argue it doesn’t fully address intersectionality, capitalism, and ableism as systemic oppression.

Disability justice incorporates race, class, gender, and environmental factors to critique how systems of power marginalize disabled people.

It moves beyond accessibility fixes to demand transformative justice and collective liberation.

How Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) and the Social Model of Disability Intersect

The social model of disability argues that disability is socially constructed, meaning that barriers, not impairments, create disability. Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) expands this idea by analyzing how systems use disability as a form of social control, reinforcing hierarchical power structures through exclusion and marginalization.

1. Conflict as a Social Regulator: Disability as an Enforced Divide

FCP sees conflict as self-regulating within social systems—disability is often positioned as an “undesirable” counterpoint to able-bodied productivity in capitalist societies.

Capitalist labor markets use ableist definitions of productivity to justify economic exclusion, keeping disabled individuals in precarious, dependent, or devalued social roles.

Example: Work requirements for welfare benefits disproportionately harm disabled individuals, reinforcing a system where economic participation is tied to able-bodied norms.

2. The Medical Model as a Tool of Social Control

The medical model of disability aligns with authoritarian social control mechanisms, pathologizing difference and removing agency from disabled individuals.

FCP argues that this mirrors broader systemic trends, where deficit-based frameworks are used to justify exclusion, whether in disability, class struggle, or race.

Example: Institutions historically medicalized neurodivergence and mental illness to enforce compliance, criminalizing behaviors that challenge the dominant order.

3. Trauma-Informed Systems and Disability Inclusion

FCP proposes that hierarchical power structures thrive on unresolved trauma, and exclusionary policies against disabled people reflect a collective trauma response.

Instead of treating disability as a “problem to solve,” a trauma-informed, relational society would:

Eliminate productivity-based worth (moving toward universal basic income & cooperative economies).

Prioritize accessibility as a baseline human right rather than an “accommodation.”

Integrate disability leadership into policy-making (disability inclusion must be systemic, not tokenized).

4. Disability as a Mechanism of Systemic Coercion

FCP argues that systems use coercion to maintain stability, and ableism serves this function in several ways:

Labor control → The threat of becoming “unproductive” forces compliance with exploitative systems.

Economic dependency → Disabled individuals are often forced into bureaucratic survival loops (SSI, SSDI, means-testing), reinforcing state control.

Social marginalization → Institutions frame disabled people as “burdens” rather than equal contributors, making it easier to justify exclusionary policies.

Example: The lack of accessible public transportation reinforces economic segregation, forcing many disabled individuals into isolation or dependence on expensive private options.

5. Restorative Disability Justice & FCP’s Solutions

FCP integrates disability justice by rejecting the notion that social stability requires exclusion. Instead, it proposes:

Non-coercive governance → Policies should be designed for accessibility from the start, not as afterthoughts.

Cooperative economic models → Moving from “productivity-based value” to “relational-based value.”

Inclusive urban planning → Cities should be built with universal design principles, benefiting everyone (not just disabled individuals).

FCP + Disability Justice: Toward a Regenerative, Accessible Future

Rather than viewing accessibility as a “burden,” FCP frames it as a fundamental design principle for a just society. The more inclusive a system is, the more stable it becomes—exclusion creates instability, requiring coercion to maintain.

Disability and the Social Model

- Oliver, Michael. The Politics of Disablement. 1990.

Connection to FCP: Oliver’s work on the social model of disability aligns with FCP’s critique of hierarchical systems that exclude marginalized groups. FCP extends this by framing disability as a systemic construct reinforcing economic and social control. - Mingus, Mia. Disability Justice and the Politics of Access. 2017.

Connection to FCP: Mingus’ emphasis on intersectional disability justice supports FCP’s argument that disability exclusion is a structural function of capitalism and trauma-driven governance. - Barnes, Colin & Mercer, Geoffrey. Exploring Disability: A Sociological Introduction. 2010.

Connection to FCP: This work critiques deficit-based frameworks of disability, reinforcing FCP’s claim that ableism functions as a coercive mechanism to maintain hierarchy and labor control.

Conclusion

I’ve integrated disability justice and the social model of disability into my Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) framework, highlighting how ableism reinforces economic and social control.