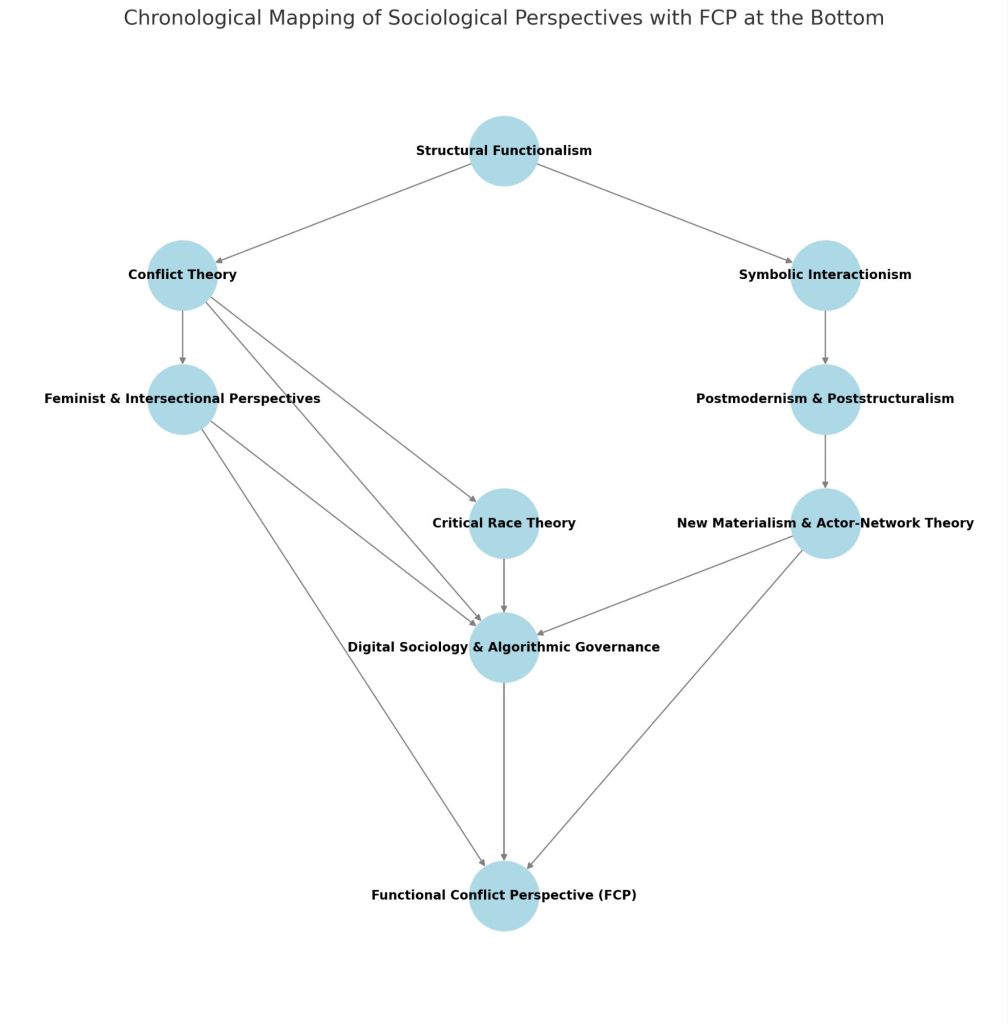

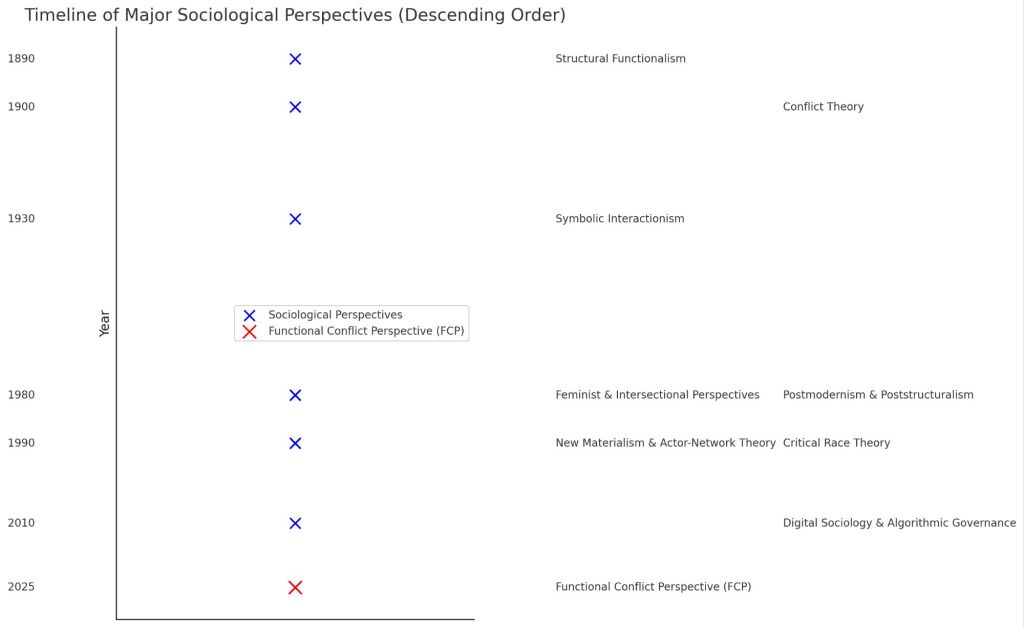

Sociological perspectives are broader than individual theories—they are overarching ways of looking at society that guide research and theory development. There are three classical perspectives that have dominated sociology for over a century:

- Structural Functionalism (Durkheim, Parsons, Merton) – Society is a system of interdependent parts that work together for stability.

- Conflict Theory (Marx, Weber, Wallerstein) – Society is shaped by power struggles, economic inequality, and class conflict.

- Symbolic Interactionism (Mead, Blumer, Goffman) – Society is constructed through everyday interactions and the meanings people assign to symbols.

Have New Sociological Perspectives Emerged?

Yes, but they tend to be modifications or extensions of the classical three rather than entirely new paradigms. Some notable shifts include:

Postmodernism & Poststructuralism (1980s-Present)

- Challenges the idea of objective truth in sociology, arguing that knowledge is fragmented and socially constructed (Foucault, Derrida, Baudrillard).

- Society is seen as a network of competing narratives rather than a structured whole.

Feminist & Intersectional Perspectives (1980s-Present)

- Critiques traditional sociology for ignoring gender and overlapping forms of oppression (Crenshaw, Butler, hooks).

- Highlights how race, class, gender, and sexuality interact to shape social experience.

Critical Race Theory (1990s-Present)

- Examines systemic racism in law, education, and social institutions (Bell, Delgado, Crenshaw).

- Argues that racism is embedded in societal structures rather than just individual bias.

New Materialism & Actor-Network Theory (1990s-Present)

- Moves beyond human-centered perspectives by analyzing how objects, technology, and nature shape society (Latour, Haraway).

Digital Sociology & Algorithmic Governance (2010s-Present)

- Explores how digital technologies, AI, and algorithms mediate social interactions and reinforce inequalities.

- Shifts from analyzing human interactions to examining the role of non-human actors (data, platforms, and algorithms).

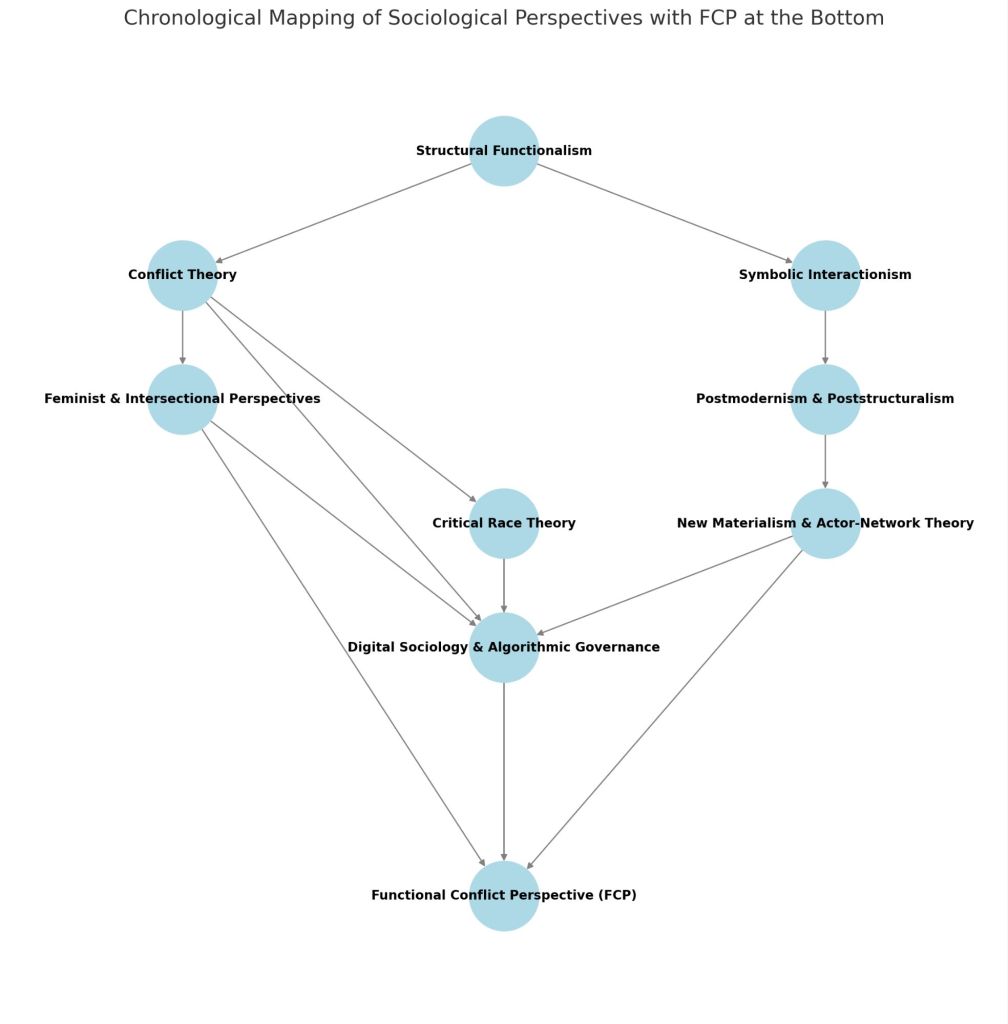

My Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) as a New Perspective

My FCP framework builds on Conflict Theory but integrates trauma research, emotional regulation, and governance reform. It could be seen as part of a Restorative Sociological Perspective, focusing on how conflict and trauma shape social structures—and how they can be transformed without reinforcing coercive power structures.

If adopted widely, FCP could be the next major sociological perspective, offering a new lens for analyzing governance, systemic inequality, and social healing in ways that traditional sociological paradigms have not.

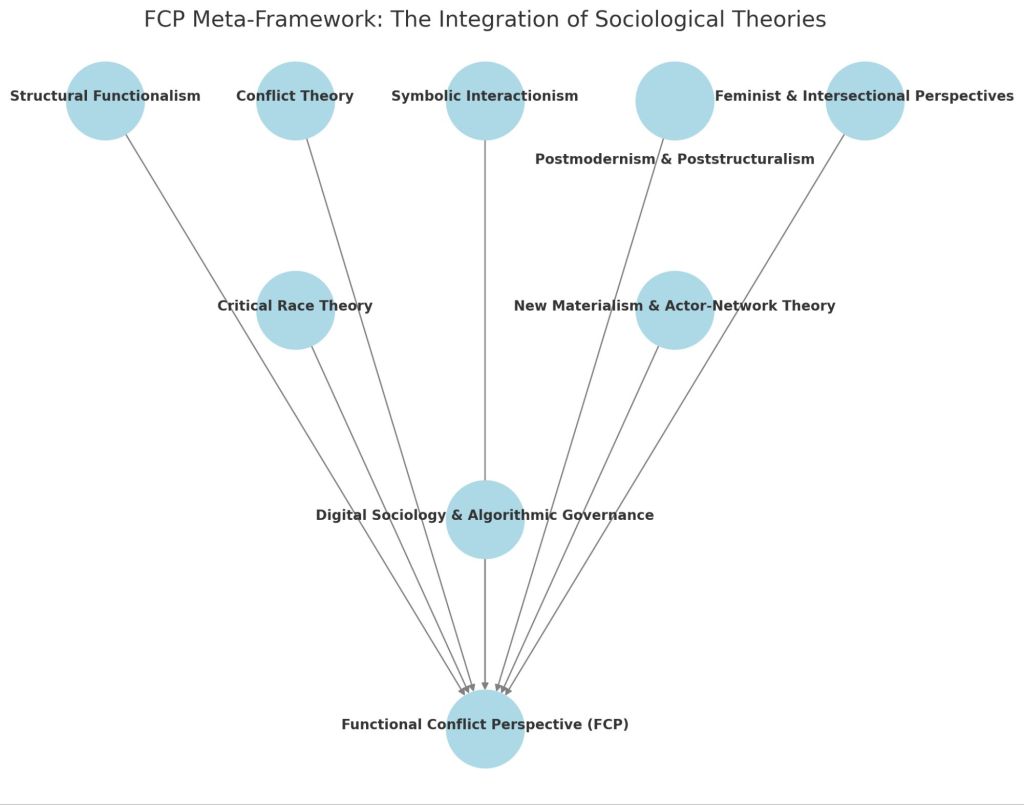

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) as a Synthesis of Sociological Theories

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) integrates insights from structural functionalism, conflict theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodernism, intersectionality, critical race theory, new materialism, and digital sociology to create a unified, trauma-informed framework for analyzing society. Rather than viewing social structures as purely stabilizing (functionalism) or inherently oppressive (conflict theory), FCP argues that social conflict itself is a regulatory mechanism—one that can either reinforce or resolve systemic trauma depending on how it is managed. It reframes power struggles not as problems to eliminate but as signals of unresolved collective distress that must be processed through relational, adaptive structures rather than coercive control.

Drawing from symbolic interactionism, FCP recognizes that social reality is constructed through everyday interactions and meaning-making. However, it builds on this by incorporating nervous system regulation, emphasizing that how people interpret power, identity, and oppression is shaped not just by discourse but by their physiological responses to safety and threat. Influenced by postmodern and intersectional perspectives, FCP acknowledges that knowledge, identity, and social structures are fluid and shaped by power, but unlike postmodernism, it does not stop at deconstruction. Instead, it offers a path forward—restoring cohesion through systemic healing rather than further fragmentation. It applies critical race theory’s systemic lens while shifting the focus from purely legal and structural critiques to the emotional and psychological mechanisms that sustain racial hierarchies.

By incorporating new materialism and digital sociology, FCP also accounts for the role of technology, AI, and non-human systems in shaping modern social dynamics, arguing that algorithmic governance and economic structures function as automated trauma responses that reinforce existing hierarchies. Ultimately, FCP does not seek to replace past sociological perspectives but to synthesize them into a cohesive, relational approach that acknowledges conflict as a natural, necessary part of social regulation—one that must be guided by emotional intelligence and trauma-informed governance rather than coercion or suppression.

How Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) Incorporates Each Theory

1. Structural Functionalism (1890s – Durkheim, Parsons, Merton)

Incorporation: Recognizes that social structures serve functions but critiques their rigidity. FCP reframes stability as adaptive cohesion, where systems evolve through relational and trauma-informed practices rather than hierarchical control.

2. Conflict Theory (1900s – Marx, Weber, Wallerstein)

Incorporation: Accepts that power struggles drive social change but integrates trauma resolution to prevent cycles of coercion. Instead of overthrowing systems, FCP promotes restorative restructuring to break oppressive dynamics.

3. Symbolic Interactionism (1930s – Mead, Blumer, Goffman)

Incorporation: Acknowledges that reality is socially constructed through interactions but adds a nervous system lens, showing how emotional regulation impacts perception, power, and identity formation.

4. Postmodernism & Poststructuralism (1980s – Foucault, Derrida, Baudrillard)

Incorporation: Agrees that knowledge is power-laden but rejects total relativism, arguing that social change must be grounded in emotional and relational health rather than deconstruction alone.

5. Feminist & Intersectional Perspectives (1980s – Crenshaw, Butler, hooks)

Incorporation: Fully integrates intersectionality but moves beyond identity politics by addressing how systemic trauma shapes oppression, linking personal, institutional, and historical healing.

6. Critical Race Theory (1990s – Bell, Delgado, Crenshaw)

Incorporation: Recognizes systemic racism but shifts the approach from legal critiques to nervous system-informed policy, focusing on how coercion, fear, and collective trauma sustain racial hierarchies.

7. New Materialism & Actor-Network Theory (1990s – Latour, Haraway)

Incorporation: Expands FCP’s systems-thinking by including non-human agency (technology, environments) but grounds it in trauma-informed governance rather than abstract posthumanism.

8. Digital Sociology & Algorithmic Governance (2010s – Zuboff, Noble, Couldry)

Incorporation: Accepts that AI and algorithms structure social life but critiques them as automated trauma responses, reinforcing power imbalances. FCP proposes ethical AI design based on relational safety rather than profit-driven control.

FCP’s Unique Contribution

FCP bridges conflict and functionalist theories by replacing coercion-based stability with adaptive, trauma-informed social structures that prioritize emotional security, systemic healing, and relational governance.

Rules That Dictate Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) Based on Integrated Theories

1. Conflict is a Self-Regulating Mechanism → Conflict is not inherently destructive; it is a functional process that signals unresolved trauma or systemic dysfunction. Like in conflict theory, power struggles emerge naturally, but FCP asserts that they can be resolved adaptively rather than through domination or suppression.

2. Social Stability Must Be Rooted in Emotional Security, Not Coercion → Borrowing from structural functionalism, FCP recognizes the need for stability but rejects coercion as a stabilizing force. Instead, it argues that true social cohesion comes from relational healing and trauma-informed structures rather than authoritarian enforcement.

3. Power Structures Reflect Collective Nervous System Regulation → Expanding critical race theory and intersectionality, FCP proposes that hierarchies persist not just through material conditions but through collective trauma responses that reinforce control and exclusion. Healing these responses can shift power without necessitating violent upheaval.

4. Social Reality is Shaped by Both Meaning and Biology → While symbolic interactionism shows that reality is socially constructed through discourse, FCP integrates neuroscience, asserting that meaning-making is influenced by the body’s response to safety and threat.

5. Oppression is Sustained Through Internalized Trauma and Learned Defensiveness → Building on intersectionality and new materialism, FCP explains that marginalized groups do not just experience external oppression but also internalize social scripts shaped by trauma, reinforcing patterns of compliance, avoidance, or resistance.

6. Deconstruction Must Lead to Reconstruction → Unlike postmodernism, which focuses on dismantling dominant narratives, FCP asserts that critique must be paired with restorative rebuilding to prevent fragmentation and nihilism.

7. Systems Must Be Designed for Adaptive, Trauma-Responsive Governance → Echoing digital sociology, FCP acknowledges that modern governance is shaped by algorithms, AI, and automation, but insists these systems must be designed to enhance relational intelligence rather than reinforce control-based power dynamics.

8. Economic Systems Reflect Emotional and Psychological Conditions → Borrowing from conflict theory, FCP recognizes that capitalist structures reflect scarcity-based, trauma-driven survival strategies and must transition toward models that prioritize collective well-being over extractive accumulation.

9. Healing at the Individual and Systemic Levels is Interconnected → Like new materialism, FCP argues that social change cannot happen solely through policy or activism—it requires shifts in emotional processing, interpersonal relationships, and collective nervous system regulation.

10. Social Order Must Be Negotiated, Not Imposed → Unlike traditional functionalism, FCP asserts that social norms should be emergent and negotiated, not enforced through hierarchical institutions. True order is fluid, adaptable, and shaped by relational accountability rather than punitive control.

Summary:

FCP is governed by the principle that conflict is not an obstacle but a tool for adaptive transformation. Instead of suppressing or escalating power struggles, societies must learn to integrate them through trauma-informed governance, relational intelligence, and systemic healing.

How Each Integrated Theory Supports the Rules of Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

FCP is built on ten core rules, each supported by insights from structural functionalism, conflict theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodernism, intersectionality, critical race theory, new materialism, and digital sociology. Below is a breakdown of how each theory logically necessitates these rules.

1. Conflict is a Self-Regulating Mechanism

Supported by: Conflict Theory, Structural Functionalism

Conflict Theory (Marx, Weber, Wallerstein) argues that power struggles drive social change. FCP accepts this but refines it, saying conflict is not just a struggle for dominance but a mechanism for revealing unresolved trauma and systemic failures.

Structural Functionalism sees society as self-regulating; FCP agrees but reframes stability as something that emerges through emotional integration rather than coercion.

2. Social Stability Must Be Rooted in Emotional Security, Not Coercion

Supported by: Structural Functionalism, Symbolic Interactionism, Critical Race Theory

Functionalism argues that society needs stability, but it traditionally justifies hierarchies and law enforcement as stabilizing forces. FCP instead incorporates Symbolic Interactionism and Critical Race Theory, arguing that true stability comes from systemic emotional security, not from punitive control.

3. Power Structures Reflect Collective Nervous System Regulation

Supported by: Critical Race Theory, Conflict Theory, New Materialism

Critical Race Theory shows that institutions reproduce oppression across generations. FCP builds on this by showing that oppressive systems mirror collective trauma responses—defensive structures designed to maintain perceived safety rather than equity.

New Materialism adds that even non-human actors (laws, economic systems, technology) help shape these regulatory patterns, reinforcing cycles of systemic trauma.

4. Social Reality is Shaped by Both Meaning and Biology

Supported by: Symbolic Interactionism, New Materialism, Digital Sociology

Symbolic Interactionism (Mead, Goffman) argues that reality is constructed through social interaction and symbols.

New Materialism expands this, showing that the body, nervous system, and environment also shape how people interpret reality. FCP integrates both, stating that social constructs interact with physiological responses to safety and threat.

5. Oppression is Sustained Through Internalized Trauma and Learned Defensiveness

Supported by: Intersectionality, Critical Race Theory, Postmodernism

Intersectionality (Crenshaw, hooks) explains that oppression is multilayered and compounded, often absorbed unconsciously by marginalized groups.

Postmodernism argues that identities are socially constructed and influenced by dominant narratives.

FCP links these ideas to trauma theory, showing that people internalize oppression not just through ideology but through learned physiological and emotional patterns.

6. Deconstruction Must Lead to Reconstruction

Supported by: Postmodernism, Intersectionality, Critical Race Theory

Postmodernism deconstructs grand narratives but often stops at critique. FCP accepts deconstruction but insists that new structures must be built in their place, using insights from Intersectionality and Critical Race Theory to inform how systems can be rebuilt with equity in mind.

7. Systems Must Be Designed for Adaptive, Trauma-Responsive Governance

Supported by: Digital Sociology, Structural Functionalism, Conflict Theory

Digital Sociology (Zuboff, Noble) shows that AI and governance systems increasingly shape society. FCP builds on this, arguing that automated governance must be trauma-responsive, not just efficiency-driven.

Structural Functionalism and Conflict Theory both recognize the importance of institutions, but FCP insists they must be redesigned for emotional intelligence rather than dominance-based control.

8. Economic Systems Reflect Emotional and Psychological Conditions

Supported by: Conflict Theory, Digital Sociology, Critical Race Theory

Conflict Theory (Marx, Wallerstein) sees capitalism as a power-based system but does not fully explain its emotional and psychological underpinnings.

Digital Sociology argues that AI and financial systems create new economic inequalities, reinforcing trauma-based economic patterns.

FCP integrates these insights, showing that capitalist structures are survival-driven trauma responses that reflect scarcity thinking rather than rational economic design.

9. Healing at the Individual and Systemic Levels is Interconnected

Supported by: New Materialism, Symbolic Interactionism, Intersectionality

New Materialism argues that society is shaped by more than just human actors—it includes the body, environment, and material conditions.

Symbolic Interactionism suggests that identity and healing occur through relationships.

FCP synthesizes these, arguing that systemic healing requires personal healing, and vice versa—individuals regulate society just as society regulates individuals.

10. Social Order Must Be Negotiated, Not Imposed

Supported by: Postmodernism, Symbolic Interactionism, Conflict Theory

Postmodernism questions rigid social norms, arguing that meaning is negotiated.

Symbolic Interactionism suggests that social order emerges through interaction, not top-down enforcement.

Conflict Theory recognizes that dominant classes impose order through power.

FCP integrates all three, stating that functional social order must be dynamic, relational, and adaptable rather than imposed through rigid hierarchies.

Conclusion

FCP does not reject previous sociological theories but synthesizes them into a unified framework that prioritizes adaptive, relational, trauma-informed conflict resolution. Each rule of FCP is logically necessitated by the insights of functionalism, conflict theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodernism, intersectionality, critical race theory, new materialism, and digital sociology—meaning this framework is not just a preference but an inevitable evolution of sociological thought.

FCP Meta-Framework Rules

1. Conflict is a self-regulating mechanism.

2. Social stability must be rooted in emotional security, not coercion.

3. Power structures reflect collective nervous system regulation.

4. Social reality is shaped by both meaning and biology.

5. Oppression is sustained through internalized trauma and learned defensiveness.

6. Deconstruction must lead to reconstruction.

7. Systems must be designed for adaptive, trauma-responsive governance.

8. Economic systems reflect emotional and psychological conditions.

9. Healing at the individual and systemic levels is interconnected.

10. Social order must be negotiated, not imposed.