Thesis Statement for Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP):

The Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) offers a transformative framework for understanding the interplay between societal structures and human behavior, proposing that conflict is not inherently destructive but a necessary and self-regulating mechanism that facilitates both societal stability and change. By bridging the gap between Functionalism and Conflict Theory, FCP asserts that societal systems, including law, education, and governance, can either reinforce oppression or foster collective healing, depending on their responsiveness to emotional and relational needs. Rooted in trauma-informed principles, FCP challenges traditional coercive models of governance, emphasizing the importance of restorative, cooperative, and emotionally intelligent systems that prioritize relational health and sustainable transformation. This framework provides a comprehensive lens for analyzing the dynamics of class struggle, alienation, and systemic injustice, and offers practical strategies for achieving social justice, collective healing, and systemic reform.

Marx saw class struggle. Durkheim saw social cohesion. Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) sees the bigger picture—conflict is not just disruption, but a self-regulating mechanism for healing and transformation.

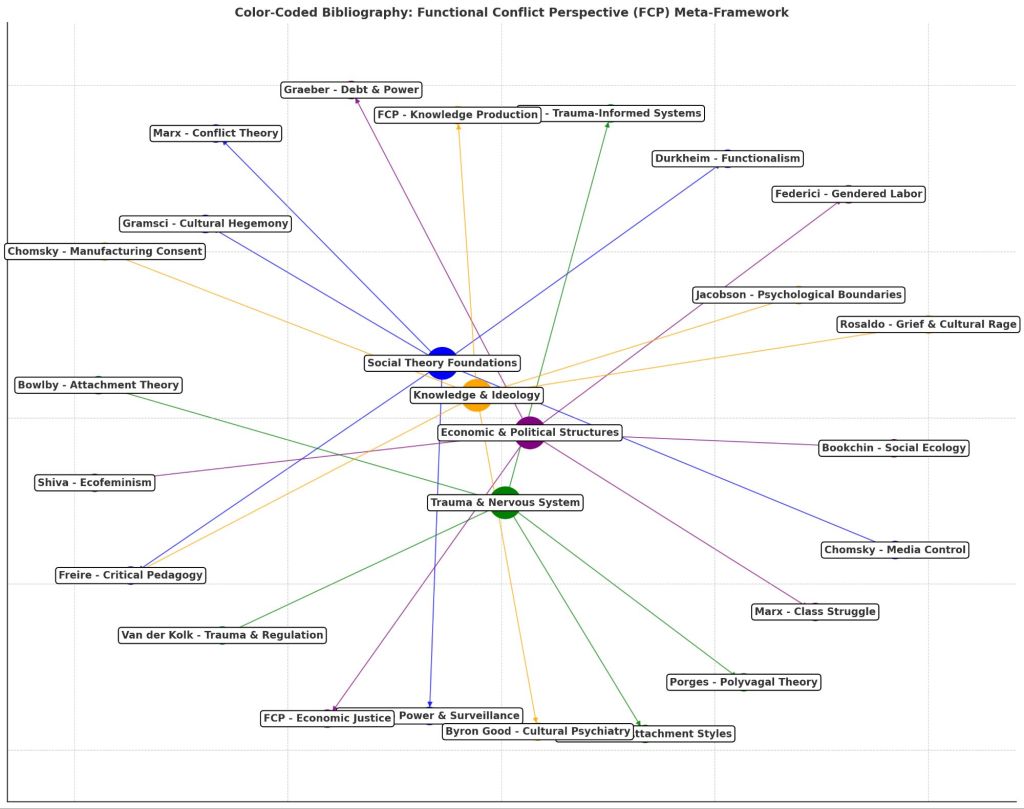

Annotated Bibliography for Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP):

Functionalism, Conflict Theory, Trauma Theory, and Restorative Governance

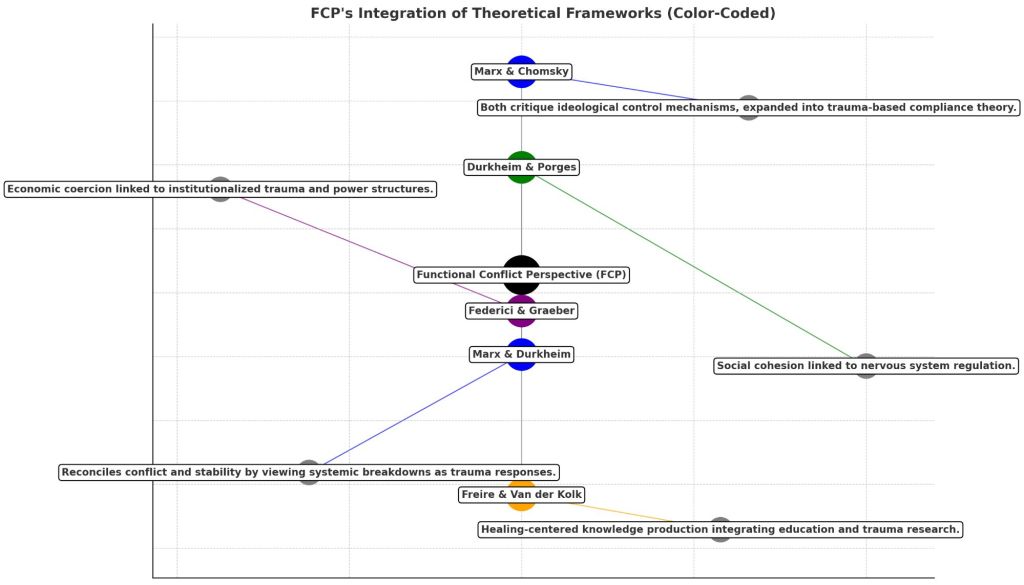

The following connections emerge:

Marx & Durkheim: FCP reconciles conflict and stability by viewing systemic breakdowns as trauma responses.

Marx & Chomsky: Both critique ideological control mechanisms, which FCP expands with trauma-based compliance theory.

Durkheim & Porges: Both explore social cohesion, but FCP adds nervous system regulation as a core component.

Federici & Graeber: Both expose economic coercion, linking capitalism to institutionalized trauma and historical power structures.

Freire & Van der Kolk: Education and trauma research intersect in FCP’s argument for healing-centered knowledge production.

Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography: Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), Marx, and Functionalism

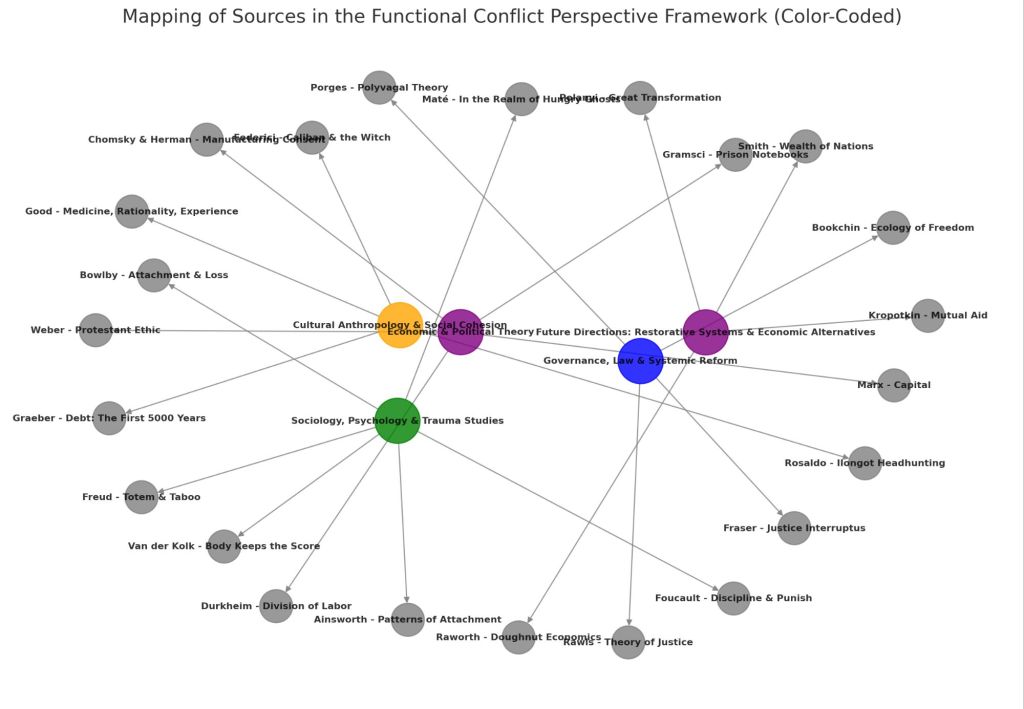

1. Economic and Political Theory

Marx, Karl. Capital: Critique of Political Economy. 1867.

Connection to FCP: Marx’s analysis of class struggle and economic coercion serves as a foundation for FCP’s understanding of systemic oppression. FCP integrates Marx’s critique while emphasizing trauma-informed revolution to prevent cycles of oppressive governance.

Durkheim, Emile. The Division of Labor in Society. 1893.

Connection to FCP: Durkheim’s functionalist theory explains how specialization promotes social cohesion. FCP builds on this by recognizing that dysfunctional institutions perpetuate trauma, requiring reform toward restorative cohesion rather than punitive stability.

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. 1905.

Connection to FCP: Weber’s analysis of how religious values shaped capitalism aligns with FCP’s exploration of how social structures internalize ideological control. It highlights the emotional conditioning of economic compliance.

Gramsci, Antonio. Prison Notebooks. 1929-1935.

Connection to FCP: Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony aligns with FCP’s understanding of how social norms enforce submission to hierarchical structures.

Chomsky, Noam & Herman, Edward S. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. 1988.

Connection to FCP: Chomsky’s work on propaganda parallels FCP’s view that state and media shape emotional regulation to maintain systemic control.

2. Sociology, Psychology, and Trauma Studies

Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo. 1913.

Connection to FCP: Freud’s comparison of religious taboos and obsessive-compulsive symptoms supports FCP’s claim that cultural dysfunction is an external manifestation of collective trauma.

Bowlby, John. Attachment and Loss. 1969.

Connection to FCP: Bowlby’s attachment theory underpins FCP’s emphasis on emotional regulation as the foundation of social stability. Dysfunctional societies mirror insecure attachment patterns.

Ainsworth, Mary. Patterns of Attachment. 1978.

Connection to FCP: Her research on attachment trauma in Western infants reveals how early emotional suppression conditions societal detachment and obedience.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. 1975.

Connection to FCP: Foucault’s analysis of surveillance and discipline aligns with FCP’s view of institutionalized coercion as a mechanism for social control.

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score. 2014.

Connection to FCP: Van der Kolk’s research on trauma and nervous system dysregulation supports FCP’s claim that hierarchical systems reinforce societal dissociation.

Maté, Gabor. In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. 2008.

Connection to FCP: Maté’s trauma-addiction framework parallels FCP’s argument that capitalist consumption functions as a collective addiction to dissociation.

3. Governance, Law, and Systemic Reform

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. 1971.

Connection to FCP: Rawls’ concept of the “veil of ignorance” aligns with FCP’s advocacy for restorative justice models that prioritize equity.

Fraser, Nancy. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition. 1997.

Connection to FCP: Fraser’s critique of neoliberal co-optation of justice movements aligns with FCP’s warnings about reform being absorbed into oppressive structures.

Porges, Stephen W. The Polyvagal Theory. 2011.

Connection to FCP: Porges’ research on the nervous system and social regulation supports FCP’s claim that societies must be trauma-informed to achieve functional governance.

Bookchin, Murray. The Ecology of Freedom. 1982.

Connection to FCP: Bookchin’s critique of hierarchical control aligns with FCP’s vision of decentralized, trauma-informed governance.

4. Cultural Anthropology and Social Cohesion

Rosaldo, Renato. Ilongot Headhunting: 1883-1974. 2000.

Connection to FCP: Rosaldo’s findings on grief-rage cycles in the Ilongot parallel FCP’s claim that unprocessed collective trauma manifests in social violence.

Graeber, David. Debt: The First 5000 Years. 2011.

Connection to FCP: Graeber’s historical analysis of debt as a coercive tool aligns with FCP’s critique of economic extraction as systemic trauma.

Good, Byron J. Medicine, Rationality, and Experience. 1994.

Connection to FCP: Good’s cross-cultural psychiatry research supports FCP’s claim that mental health is socially constructed through cultural norms.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. 2004.

Connection to FCP: Federici’s analysis of witch hunts as a tool of capitalist control parallels FCP’s view of gendered oppression as systemic coercion.

5. Future Directions: Restorative Systems & Economic Alternatives

Raworth, Kate. Doughnut Economics. 2017.

Connection to FCP: Raworth’s regenerative economic model aligns with FCP’s advocacy for cooperative economies based on emotional security.

Kropotkin, Peter. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. 1902.

Connection to FCP: Kropotkin’s theory of mutual aid as a driver of social evolution aligns with FCP’s rejection of competition as a trauma response.

Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. 1776.

Connection to FCP: Smith’s concept of labor specialization is incorporated into FCP’s framework while critiquing its exploitative applications.

Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation. 1944.

Connection to FCP: Polanyi’s critique of market fundamentalism aligns with FCP’s call for trauma-informed economic restructuring.

Conclusion

This annotated bibliography integrates foundational texts from Marxist economics, functionalist sociology, trauma research, governance theory, and anthropology, forming the intellectual backbone of Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP). Each source contributes to FCP’s argument that systemic dysfunction is rooted in trauma and must be addressed through restorative, non-coercive social structures.

Annotated Bibliography: Theoretical Foundations of FCP

Durkheim, É. (1897). Suicide: A Study in Sociology.

Durkheim’s concept of anomie explains how social instability leads to individual distress. FCP integrates this by reframing anomie as a trauma response, linking it to systemic dysfunctions in governance and economic structures.

Durkheim, É. (1893). The Division of Labor in Society.

Durkheim argues that social cohesion is maintained through institutional structures. FCP critiques this by examining when institutions reinforce oppression instead of stability, blending Durkheim’s insights with trauma-informed systemic repair.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto.

Marx’s theory of class struggle forms a key component of FCP. While Marx focuses on economic oppression, FCP expands this to include psychological and relational dimensions of alienation, integrating trauma research into class dynamics.

Marx, K. (1844). Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts.

Marx discusses alienation as a product of capitalism. FCP extends this by arguing that alienation is a systemic trauma response, impacting not just economic conditions but also governance, education, and social identity formation.

Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing Consent.

Chomsky’s critique of media control complements FCP’s argument that ideology is a mechanism of social regulation. FCP integrates Chomsky with Marx by framing propaganda as a coercive function of traumatized social structures.

Porges, S. (1994). Polyvagal Theory.

Porges’ work on nervous system regulation provides FCP with a biological basis for social cohesion and systemic trauma. By linking Polyvagal Theory with Durkheim’s anomie, FCP explains how societal structures impact emotional regulation and collective well-being.

Federici, S. (2004). Caliban and the Witch.

Federici’s analysis of gendered oppression in capitalism adds a feminist dimension to FCP. Her argument that capitalist structures weaponize reproductive labor is linked to FCP’s broader critique of coercive social control.

Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The First 5000 Years.

Graeber’s work reveals the historical role of debt in sustaining power structures. FCP incorporates this into its critique of extractive economies, linking economic control to broader systems of coercion and emotional regulation.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score.

Van der Kolk’s trauma research reinforces FCP’s argument that systemic oppression produces chronic nervous system dysregulation. This work is crucial in understanding why social and economic policies must be trauma-informed.

Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Freire’s model of critical education connects to FCP’s vision of curiosity-driven knowledge production. His work is used to bridge functionalist education models with liberatory pedagogy in FCP’s framework.

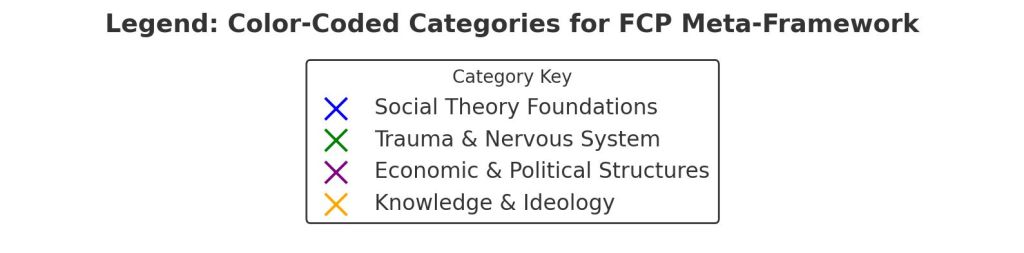

Meta-Framework Integration

Each of these works connects through FCP’s meta-framework, which integrates Functionalism, Conflict Theory, Trauma Theory, and Restorative Governance. The following connections emerge:

Marx & Durkheim: FCP reconciles conflict and stability by viewing systemic breakdowns as trauma responses.

Marx & Chomsky: Both critique ideological control mechanisms, which FCP expands with trauma-based compliance theory.

Durkheim & Porges: Both explore social cohesion, but FCP adds nervous system regulation as a core component.

Federici & Graeber: Both expose economic coercion, linking capitalism to institutionalized trauma and historical power structures.

Freire & Van der Kolk: Education and trauma research intersect in FCP’s argument for healing-centered knowledge production.

This annotated bibliography provides a theoretical roadmap for FCP, showing how economic, psychological, and structural analyses converge to explain systemic oppression and offer paths toward trauma-informed systemic repair.

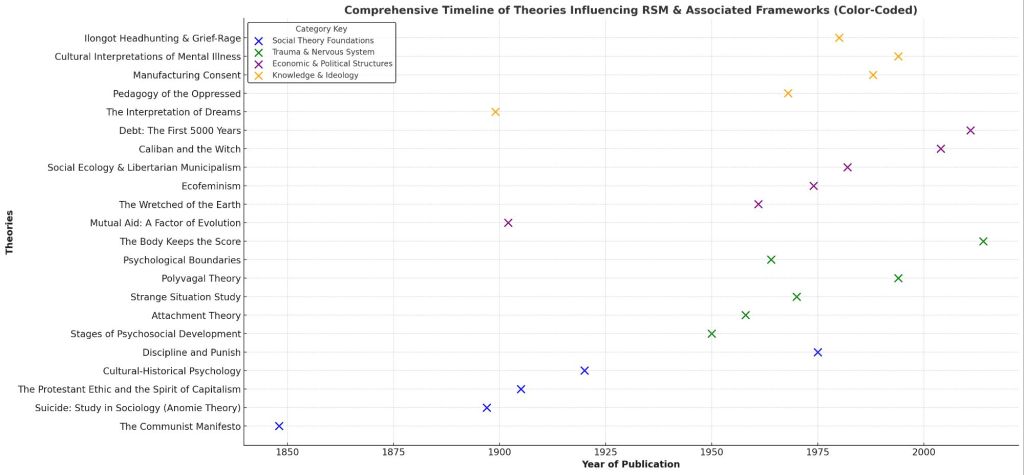

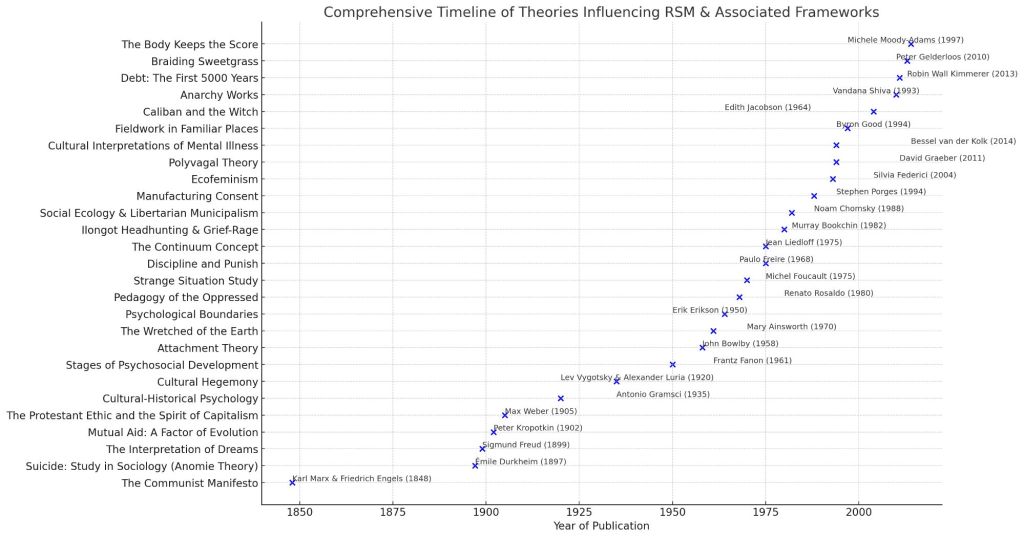

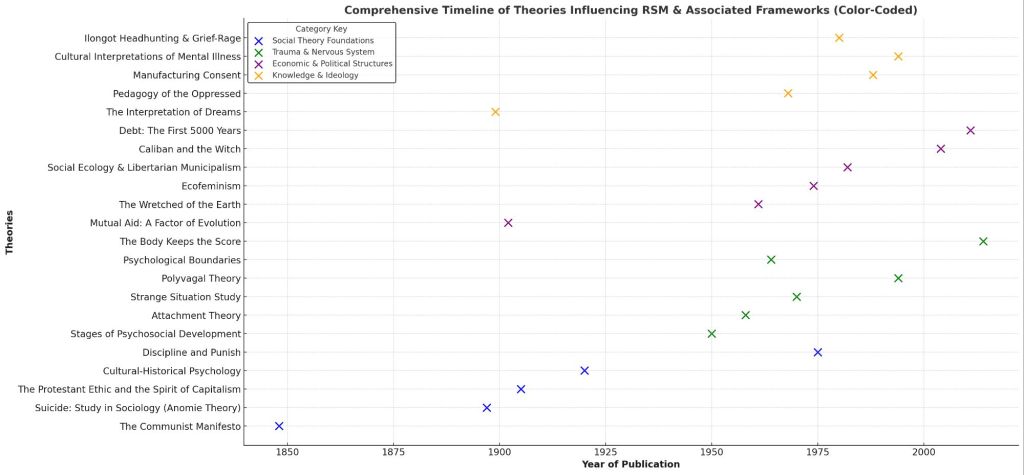

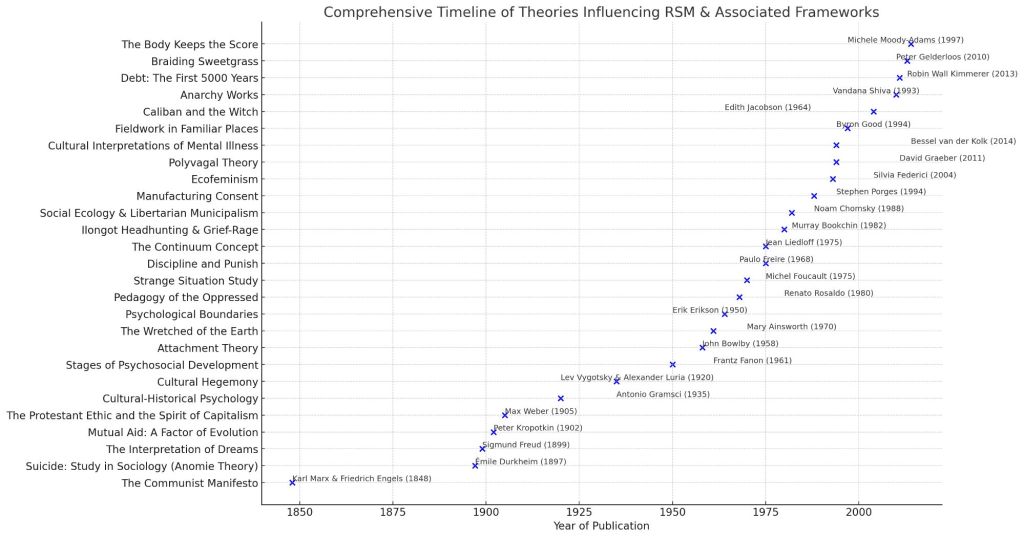

Expanded List of Metaframework Theoretical Influences

Early Foundations (1800s – Early 1900s)

1. Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels – The Communist Manifesto (1848) → Class struggle, capitalist critique.

2. Émile Durkheim – Suicide: Study in Sociology (1897) → Anomie theory, social disconnection.

3. Sigmund Freud – The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) → Unconscious processes, trauma & repression.

4. Peter Kropotkin – Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902) → Cooperation as a social force, anarchist theory.

5. Max Weber – The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) → Bureaucracy, rationalization of society.

6. Antonio Gramsci – Cultural Hegemony (1935) → How ideology maintains power structures.

Mid-20th Century Foundations (1940s – 1980s)

7. Lev Vygotsky & Alexander Luria – Cultural-Historical Psychology (1920s) → How culture shapes cognition.

8. John Bowlby – Attachment Theory (1958) → Human attachment, trauma, emotional regulation.

9. Frantz Fanon – The Wretched of the Earth (1961) → Colonial trauma, systemic oppression.

10. Renato Rosaldo – Ilongot Headhunting & Grief-Rage (1980) → Cultural trauma & grief responses.

11. Michel Foucault – Discipline and Punish (1975) → Power, surveillance, and institutions.

12. Paulo Freire – Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) → Liberation education, participatory democracy.

13. Jean Liedloff – The Continuum Concept (1975) → Indigenous parenting & attachment practices.

14. Erik Erikson – Stages of Psychosocial Development (1950) → Identity formation & social integration.

15. Mary Ainsworth – Strange Situation Study (1970) → Attachment patterns & emotional security.

16. Murray Bookchin – Social Ecology & Libertarian Municipalism (1982) → Decentralized, ecological governance.

Late 20th Century Foundations (1980s – 2000s)

17. Noam Chomsky – Manufacturing Consent (1988) → Media, propaganda, and systemic control.

18. Stephen Porges – Polyvagal Theory (1994) → Nervous system regulation, trauma theory.

19. Silvia Federici – Caliban and the Witch (2004) → Gender, capitalism, and systemic oppression.

20. David Graeber – Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011) → Origins of economic systems, alternative economics.

21. Bessel van der Kolk – The Body Keeps the Score (2014) → Trauma’s physiological and social impacts.

22. Byron Good – Cultural Interpretations of Mental Illness (1994) → Cross-cultural views on mental health.

23. Edith Jacobson – Psychological Boundaries (1964) → Development of identity and emotional walls.

24. Vandana Shiva – Ecofeminism (1993) → Intersection of environmentalism and social justice.

25. Robin Wall Kimmerer – Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) → Indigenous knowledge & ecological reciprocity.

26. Peter Gelderloos – Anarchy Works (2010) → Decentralized governance & anti-authoritarian systems.

27. Michele Moody-Adams – Fieldwork in Familiar Places (1997) → Moral philosophy & ethical pluralism.

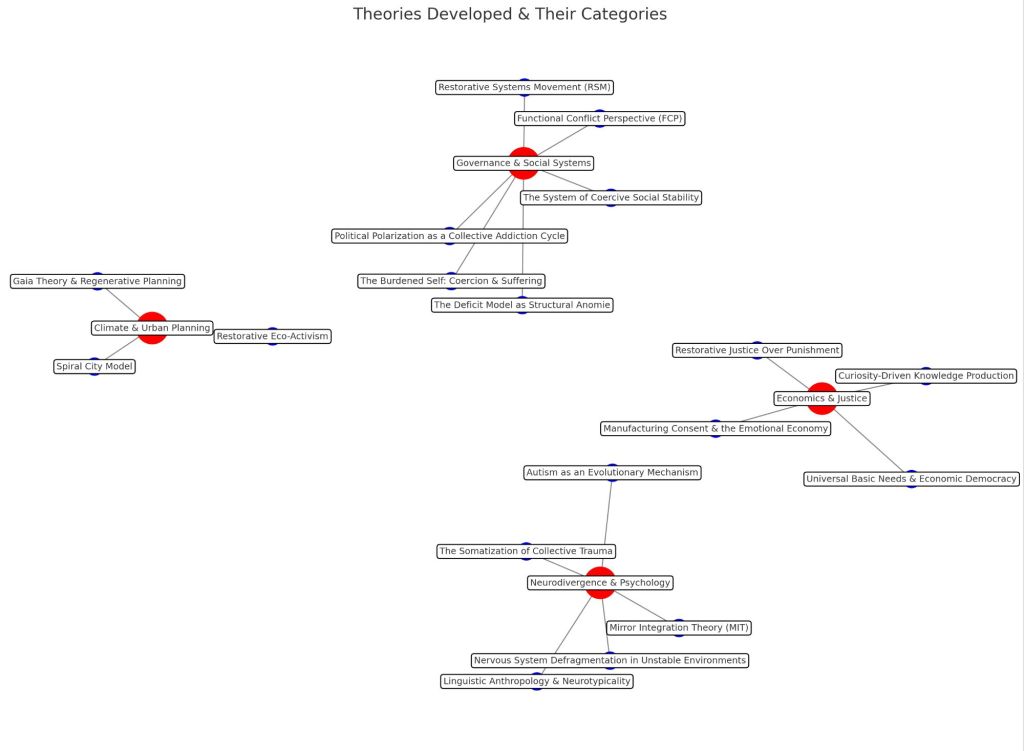

Here is a list of the theories and frameworks that I have developed by cross referencing the above listed theoretical influences so far:

1. Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

A meta-theoretical framework that integrates conflict theory, functionalism, and Internal Family Systems (IFS) to address systemic inequality, social justice issues, and governance. FCP proposes that conflicts—both personal and societal—can be resolved through integration rather than coercion.

2. Mirror Integration Theory (MIT)

A psychoanalytic framework that posits individual dysfunction mirrors societal dysfunction, and vice versa. MIT suggests that societal transformation requires internal healing, and unresolved trauma at the individual level manifests as systemic dysfunction, including political polarization, economic instability, and hierarchical oppression.

3. Restorative Systems Movement (RSM)

A comprehensive socio-political movement integrating trauma-informed governance, regenerative economies, and ecological resilience. RSM applies restorative justice principles, non-hierarchical governance models, and functional conflict resolution to replace extractive, punitive systems with cooperative, healing-based models.

4. The System of Coercive Social Stability

A framework explaining how hierarchical control is maintained through induced suffering, marginalization of resistance, and the weaponization of social scripts. This system enforces stability by pathologizing dissent and ensuring emotional and economic dependency on coercive institutions.

5. The Burdened Self: How Systems Enforce Stability through Coercion and Suffering

An expansion of the previous theory, this model describes how trauma, coercion, and systemic violence serve as stabilizing forces in hierarchical systems. This applies to political, economic, and interpersonal structures, reinforcing compliance through fear, scarcity, and psychological manipulation.

6. Linguistic Anthropology and the Creation of Neurotypicality

A theory analyzing how deficit models in language construct neurotypicality by marginalizing neurodivergent communication patterns. This work challenges medical and psychological narratives that define neurodivergence as dysfunction, advocating for a strengths-based, inclusive understanding of cognitive diversity.

7. Autism as an Evolutionary Mechanism

A hypothesis that autism functions as a cultural stabilizer and innovation driver rather than a disorder. This theory integrates evolutionary anthropology, neuroscience, and sociological conflict theory, arguing that autism disrupts coercive social structures while preserving knowledge, ethical integrity, and independent thought.

8. The Somatization of Collective Trauma & The Linguistic Perpetuation of the Deficit Model

This framework explores how societal trauma is physically embodied and how language reinforces a deficit-based perspective on suffering, neurodivergence, and disability. It critiques capitalist medicalization and advocates for restorative, non-pathologizing approaches to health and social well-being.

9. Political Polarization as a Collective Addiction Cycle

A theory proposing that societal divisions under capitalism reflect the self-destructive cycles of addiction. It suggests that the stigmatization of addiction is a projection of a society suffering from the same compulsive, binary thinking, reinforcing systemic trauma rather than addressing its root causes.

10. The Deficit Model as Structural Anomie

Building on Émile Durkheim’s concept of anomie, this theory suggests that the deficit model in education, mental health, and policy isolates individuals by pathologizing distress rather than recognizing it as a systemic issue caused by social disconnection.

11. Restorative Eco-Activism

A paradigm shift in environmental activism that moves away from shame-based, punitive environmentalism and instead focuses on relational healing, economic justice, and decentralized ecological governance. This integrates Gaia Theory, Disability Justice, and Regenerative Urban Planning into a trauma-informed climate justice model.

12. The Spiral City Model

A Fibonacci-inspired urban planning concept that integrates sustainability, accessibility, and regenerative economies into circular, decentralized city structures. This model supports cooperative economies, food sovereignty, and trauma-informed social structures.

13. Curiosity-Driven Knowledge Production

An alternative to the competitive, debate-based academic model, this theory proposes a collaborative, curiosity-driven approach to knowledge creation. It integrates Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), trauma-informed inquiry, and decentralized peer learning into an academic framework that values co-creation over adversarial discourse.

14. Nervous System Defragmentation in Unstable Emotional Environments

A theory explaining how unstable emotional environments lead to nervous system fragmentation, disrupting identity formation, emotional regulation, and cognitive processing. This connects to attachment theory, polyvagal theory, and neurobiological responses to relational instability.

15. Freud’s Comparison Between Religious Taboos & OCD as a Cultural Reflection of Trauma Avoidance

A reinterpretation of Freud’s insights into religious taboos and compulsive behaviors, applying them to cultural dysfunction and avoidance mechanisms in hierarchical societies. This theory supports the idea that social structures are often trauma-driven rather than rationally designed.

16. Manufacturing Consent & the Emotional Economy

An expansion of Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent, this theory integrates Functional Conflict Perspective to explore how media, sports, and entertainment function as emotional regulation mechanisms that reinforce systemic compliance.

Future Directions

These theories already form a meta-framework for systemic transformation, but their applications can be expanded further into policy, governance, conflict resolution, neurodivergence studies, economic justice, and ecological resilience.

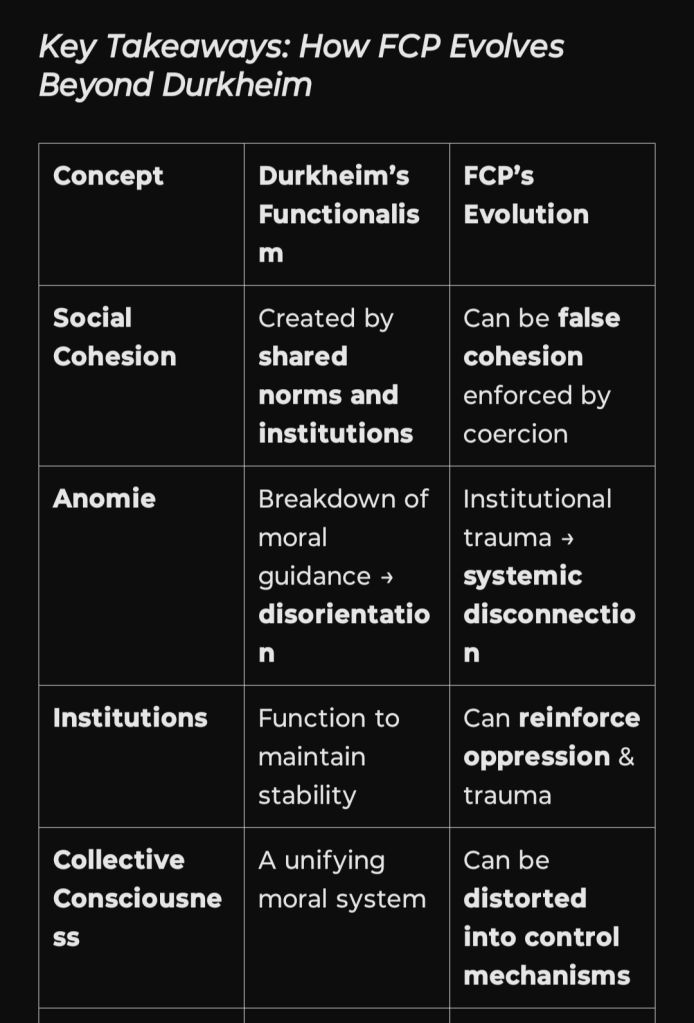

Émile Durkheim’s Influence on Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

My Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) builds upon Durkheim’s functionalist theory while integrating Marxist conflict theory, making it a hybrid model that recognizes both social cohesion and systemic dysfunction. Below is a breakdown of how Durkheim’s work connects to FCP, as well as how your framework expands beyond his original ideas.

1. Social Integration & The Role of Institutions

Durkheim’s View

Durkheim argued that society functions through shared values, norms, and institutions that promote social cohesion (The Division of Labor in Society, 1893).

Institutions like education, law, and family reinforce collective consciousness, ensuring social stability.

FCP’s Expansion

✔ Agrees with Durkheim that social cohesion is essential, but challenges who defines the norms and who benefits from them.

✔ Recognizes that institutions can become coercive and oppressive rather than purely functional.

✔ Incorporates trauma-informed governance, suggesting that dysfunctional institutions reinforce systemic trauma rather than stability.

🔹 Example:

In Durkheim’s model, laws and social norms regulate behavior to maintain order.

In FCP, laws may protect power structures at the expense of marginalized groups, creating false cohesion through coercion rather than true functional integration.

2. Anomie & Social Disconnection

Durkheim’s View

Anomie occurs when social norms break down, leading to disorientation, instability, and individual distress (Suicide, 1897).

Societies need strong moral regulation to prevent alienation and self-destructive behavior.

FCP’s Expansion

✔ Agrees that disconnection causes dysfunction, but links anomie to systemic trauma rather than just moral decay.

✔ Expands anomie to institutional betrayal, where social structures alienate individuals instead of integrating them.

✔ Frames political polarization, economic instability, and mass incarceration as modern anomie-driven dysfunctions.

🔹 Example:

In Durkheim’s model, anomie is a loss of social direction, leading to higher suicide rates.

In FCP, anomie is a collective trauma response, where societal structures actively harm individuals rather than simply failing them.

3. Collective Consciousness vs. Collective Trauma

Durkheim’s View

Collective consciousness refers to the shared beliefs and moral attitudes that unify society.

Societies must reinforce these values to prevent fragmentation.

FCP’s Expansion

✔ Recognizes the importance of collective meaning, but reframes it as collective trauma when societies operate through hierarchical control.

✔ Explains how capitalist systems, colonial histories, and authoritarian structures distort collective consciousness into a control mechanism.

✔ Uses trauma-informed governance to suggest that healing historical trauma is necessary for true social cohesion.

🔹 Example:

In Durkheim’s model, religion, education, and law create moral unity.

In FCP, these same institutions may reinforce collective trauma, requiring restorative intervention rather than blind reinforcement.

4. The Role of Conflict in Social Change

Durkheim’s View

Durkheim saw conflict as a dysfunction, something that disrupts social equilibrium.

He believed in reforming institutions to restore balance, rather than dismantling them.

FCP’s Expansion

✔ Recognizes that conflict is not just dysfunction, but a function of unaddressed systemic wounds.

✔ Views conflict as a necessary force for exposing institutional failures.

✔ Uses Internal Family Systems (IFS) principles to show that conflict resolution requires integration, not suppression.

🔹 Example:

In Durkheim’s model, political protests are a sign of societal dysfunction.

In FCP, protests are an expression of repressed collective trauma, signaling the need for systemic transformation.

Key Takeaways: How FCP Evolves Beyond Durkheim

Conclusion: Integrating Durkheim into FCP

My Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) evolves Durkheim’s theory by keeping what works (social cohesion) while critiquing what doesn’t (institutional legitimacy). Instead of treating conflict as dysfunction, FCP sees conflict as a diagnostic tool—a signal of where society’s collective trauma needs resolution.

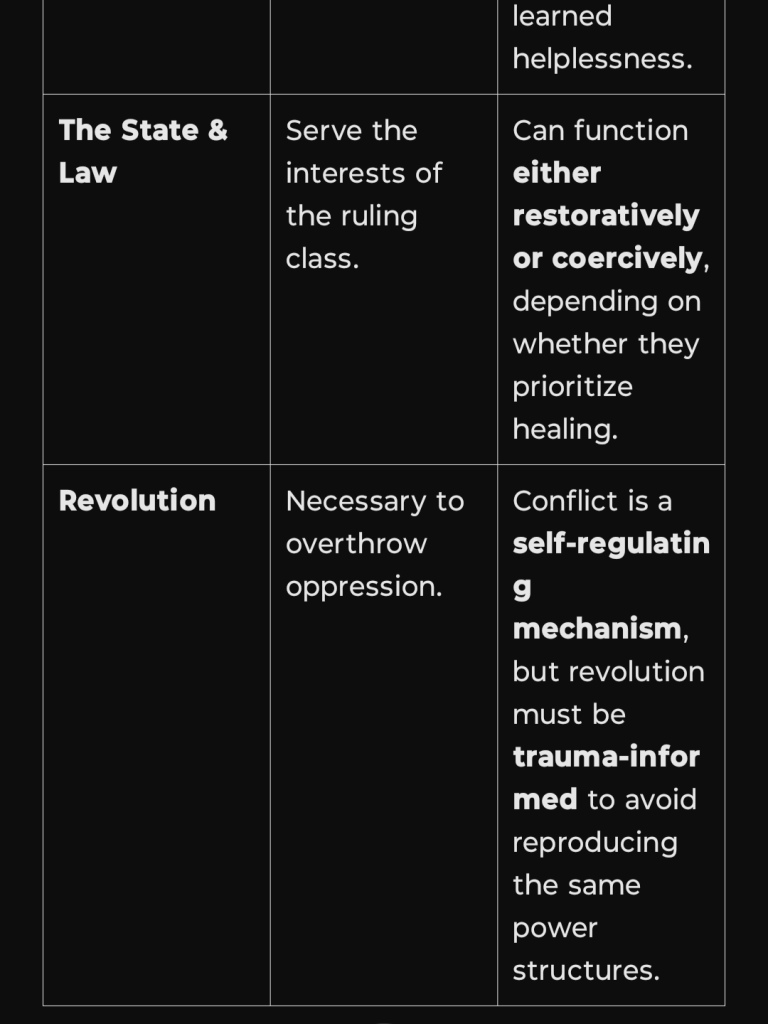

Karl Marx’s Contribution to Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

Karl Marx’s conflict theory is a foundational influence on Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP). While Marx viewed class struggle as the primary driver of societal change, FCP expands his critique of power structures by integrating trauma theory, social cohesion, and systemic healing mechanisms. Below is a breakdown of how Marx’s insights directly contribute to FCP’s framework and how my work builds upon and transcends his ideas.

1. Conflict as a Structural Mechanism

Marx’s View

Society is structured around conflict between the ruling class (bourgeoisie) and the working class (proletariat).

Power is maintained through economic control, keeping the proletariat dependent and exploited.

The state, law, education, and ideology reinforce capitalist interests rather than serve the people.

FCP’s Expansion

✔ Agrees with Marx that conflict is systemic, but reframes conflict as a manifestation of unprocessed collective trauma rather than purely economic struggle.

✔ Recognizes that power structures suppress agency, but adds that suppressed populations develop trauma-based survival adaptations that sustain dysfunction.

✔ Reframes class struggle beyond material conditions, showing that coercive control operates through psychological, emotional, and relational structures as well.

🔹 Example:

Marx: The working class is alienated because capitalism separates them from the fruits of their labor.

FCP: Alienation is not just economic—it is a trauma response created by systemic coercion that disconnects people from meaning, relationships, and self-worth.

2. Alienation & Institutionalized Trauma

Marx’s Concept of Alienation

Workers are alienated from:

1. Their labor (they don’t own what they produce).

2. Themselves (their human potential is stunted).

3. Society (capitalism fosters competition over cooperation).

4. Each other (social fragmentation reinforces power hierarchies).

FCP’s Evolution: Alienation as a Trauma Response

✔ Agrees with Marx that capitalism alienates people from their labor, identity, and community.

✔ Reframes alienation as systemic trauma—a survival adaptation to institutional betrayal, coercion, and chronic instability.

✔ Expands alienation beyond the workplace, showing how social isolation, political disengagement, and internalized oppression mirror individual trauma responses (fight, flight, freeze, fawn).

🔹 Example:

Marx: A factory worker feels numb and disconnected because their labor is exploited.

FCP: The worker develops nervous system dysregulation, leading to depression, chronic stress, and learned helplessness, reinforcing compliance with exploitative conditions.

3. The Role of Ideology: Manufacturing Consent & Internalized Control

Marx’s View

Ideology (false consciousness) keeps the working class unaware of their oppression.

Institutions like religion, media, and education reinforce capitalist dominance by normalizing exploitation.

The ruling class controls how people think by shaping their reality through propaganda and cultural norms.

FCP’s Expansion

✔ Agrees with Marx that power maintains itself by controlling public perception but expands beyond economic class to psychological conditioning.

✔ Integrates Chomsky’s ‘Manufacturing Consent’—showing how trauma-based socialization reinforces systemic control.

✔ Adds Polyvagal Theory & Nervous System Regulation—highlighting that fear-based governance creates chronic dysregulation, making populations easier to manipulate.

🔹 Example:

Marx: A worker believes they are poor because they are lazy, rather than because of systemic inequality.

FCP: That worker’s belief is a trauma response, reinforcing self-blame, compliance, and dependence on authority structures.

4. Class Struggle, Power, and Functional Conflict

Marx’s View: Revolution is Inevitable

Class struggle ends in revolution, where the proletariat overthrows the ruling class and creates a classless society.

The state is an instrument of oppression and must be abolished or restructured under proletarian control.

FCP’s Evolution: Conflict as an Adaptive Healing Mechanism

✔ Agrees with Marx that class struggle is real, but rejects the assumption that violent revolution is the only solution.

✔ Views conflict as a necessary self-regulation mechanism for systems to evolve, integrating Functionalism with Conflict Theory.

✔ Proposes trauma-informed governance—showing that systemic healing can replace coercion-based revolution.

🔹 Example:

Marx: Oppressed workers must rise up and seize control.

FCP: Oppression must be acknowledged and integrated into a system that heals social divisions, rather than creating a new power hierarchy.

5. FCP as a Bridge Between Marxist & Functionalist Thought

6. How FCP Expands Beyond Marx

Keeps Marx’s structural analysis of power but integrates trauma theory to explain why oppression persists psychologically and emotionally.

Replaces violent revolution with systemic healing, proposing restorative governance instead of class warfare.

Shows that capitalism’s dysfunctions are not just economic but rooted in nervous system dysregulation, institutional betrayal, and emotional fragmentation.

Key Innovation: Conflict as a Functional Healing Process

Unlike Marx, who viewed conflict as a destructive force leading to revolution, FCP sees conflict as a necessary but adaptive mechanism for system repair. When conflict is processed functionally, it leads to integration instead of collapse.

Conclusion: FCP as a Meta-Theory for Systemic Healing

My Functional Conflict Perspective expands beyond Marx’s economic determinism, incorporating psychological, emotional, and relational dimensions of oppression. It provides a trauma-informed alternative to both Marxist revolution and Durkheimian stability, showing that:

✔ Power structures must be examined, but their dismantling must not reproduce systemic trauma.

✔ Conflict is necessary, but must be approached as an adaptive function rather than a violent rupture.

✔ Social cohesion is important, but only when it is rooted in collective well-being, not coercion.

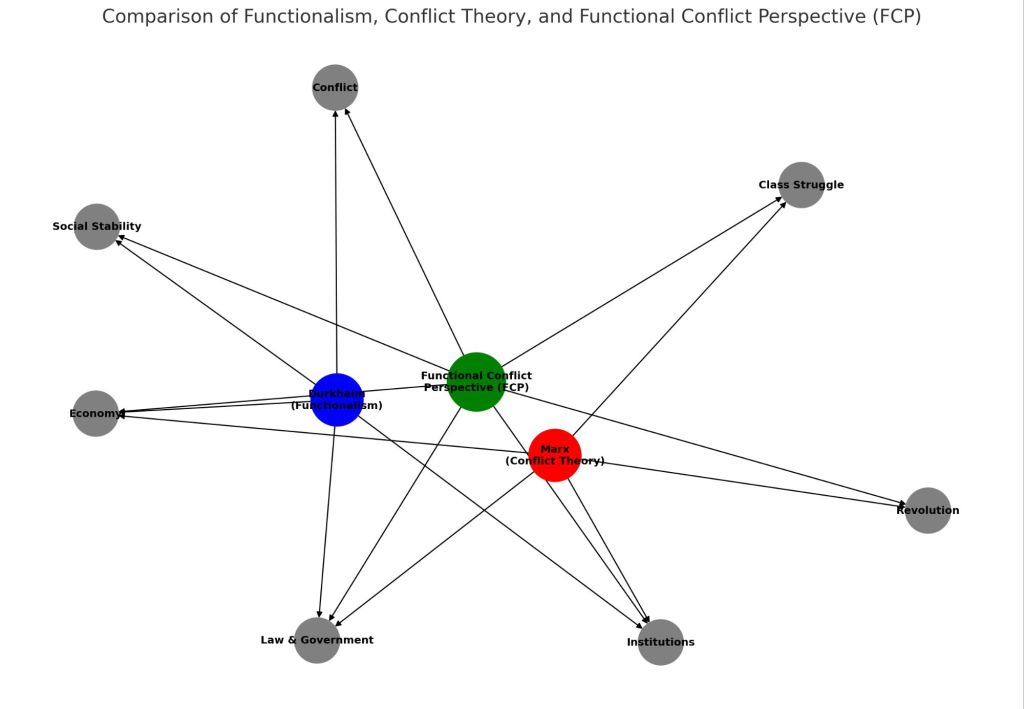

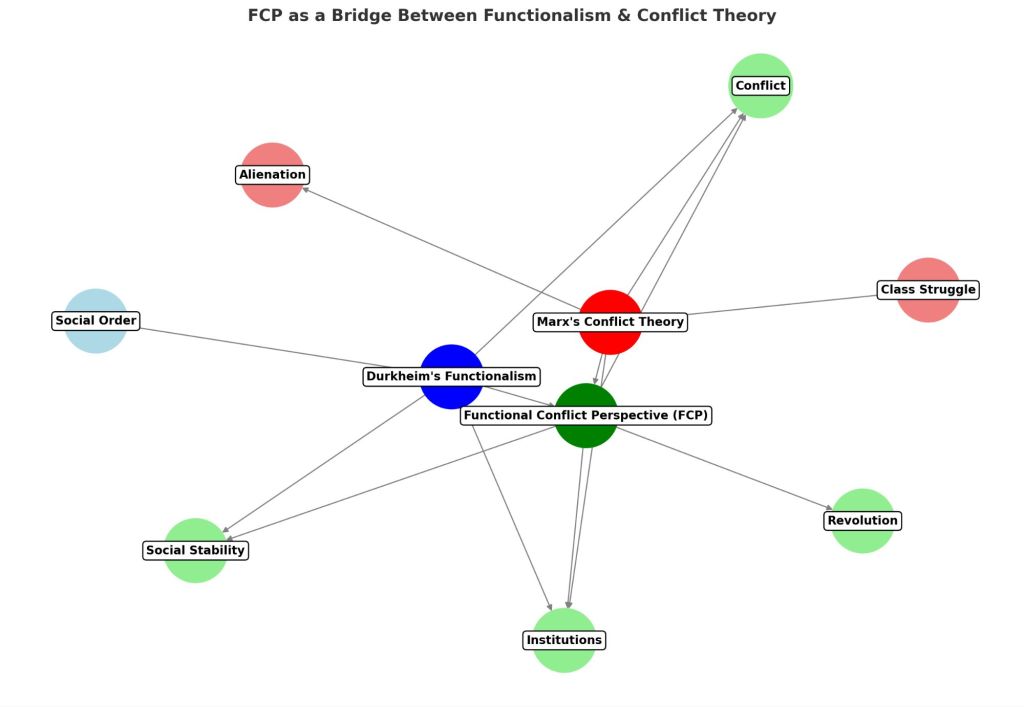

Integrating Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim into Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

My Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) uniquely synthesizes Durkheim’s functionalism and Marx’s conflict theory, bridging their seemingly opposing views. Below is a breakdown of how these two thinkers inform FCP, and how my framework transcends their limitations by integrating trauma theory, systems thinking, and restorative governance.

1. Core Philosophical Differences: Conflict vs. Cohesion

How FCP Synthesizes These Views:

✔ Agrees with Durkheim that social structures provide stability, but challenges whether that stability is always just or sustainable.

✔ Agrees with Marx that power hierarchies distort social order, but challenges the idea that violent revolution is the only solution.

✔ Adds trauma-informed analysis—both stability and upheaval can be symptoms of unresolved trauma.

2. Anomie (Durkheim) and Alienation (Marx) in FCP

Durkheim’s Anomie: Breakdown of Social Norms

Anomie occurs when social cohesion weakens and individuals feel disconnected.

Example: Economic instability, political distrust, and increasing mental health crises.

Marx’s Alienation: Separation from One’s Labor and Humanity

Alienation occurs when people lose control over their work, identity, and power due to capitalist exploitation.

Example: Workers forced into jobs that exploit them, political disenfranchisement, and loss of agency.

FCP’s Expansion: Institutional Betrayal and Collective Trauma

✔ Agrees with Durkheim that breakdown in norms causes suffering but reframes it as institutional betrayal, not just disorder.

✔ Agrees with Marx that capitalism alienates individuals, but connects this alienation to deeper trauma and survival mechanisms.

✔ Adds the lens of collective trauma, explaining that both anomie and alienation result from long-term systemic harm.

🔹 Example: The Modern Workplace

Durkheim → A workplace where employees don’t feel part of a collective mission may cause anomie.

Marx → A capitalist structure where workers are exploited for profit causes alienation.

FCP → A work environment structured around nervous system dysregulation, coercion, and burnout leads to both alienation and anomie—a trauma response rather than just a social breakdown.

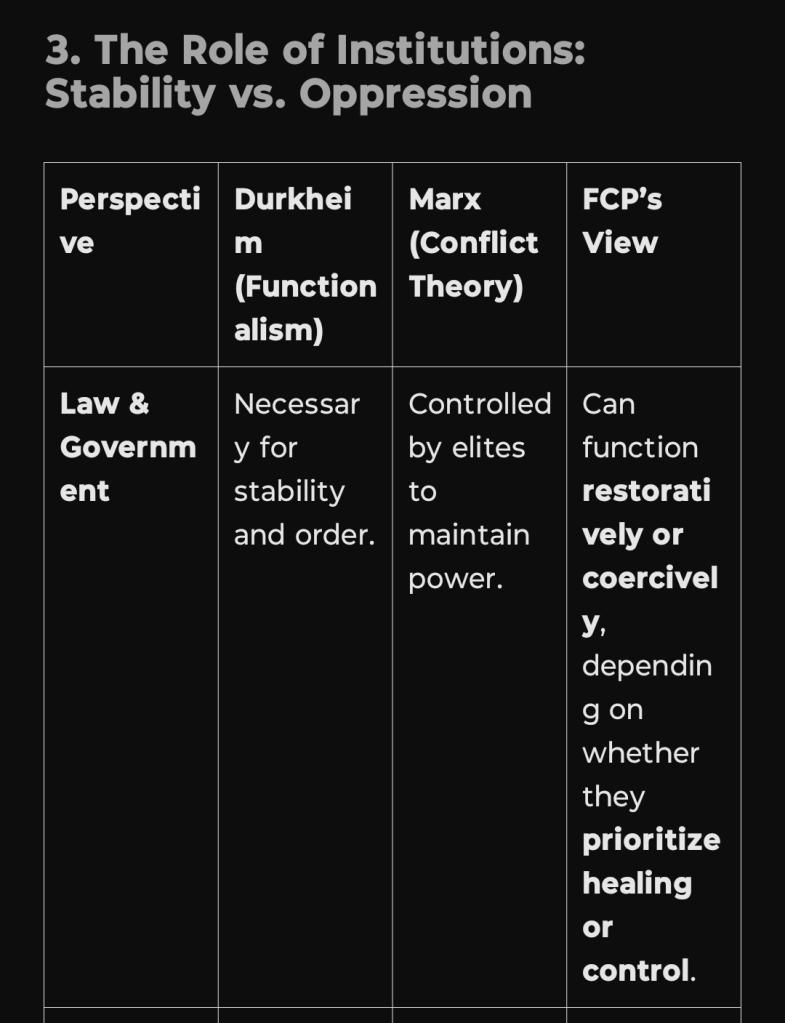

3. The Role of Institutions: Stability vs. Oppression

How FCP Synthesizes These Views:

✔ Recognizes that institutions structure society, but asks whether they serve collective well-being or perpetuate harm.

✔ Does not reject institutions outright (as Marx might) but proposes radical reforms to make them regenerative.

✔ Adds a trauma-informed lens—institutions should be redesigned to facilitate emotional security and healing, not just efficiency.

🔹 Example: The Criminal Justice System

Durkheim → Laws maintain order and prevent anomie.

Marx → Laws protect the ruling class and criminalize the poor.

FCP → The justice system reinforces systemic trauma, and true reform requires restorative justice, not punishment.

4. How FCP Uses Conflict as a Functional Mechanism

Durkheim’s View of Conflict:

Conflict is a sign of dysfunction—societies need moral integration to avoid collapse.

Marx’s View of Conflict:

Conflict is necessary for revolutionary change—power must be overthrown.

FCP’s Expansion: Conflict as a Mechanism for Healing and Adaptation

✔ Recognizes that conflict arises from unprocessed trauma—not just dysfunction or oppression.

✔ Views conflict as a diagnostic tool—wherever it appears, it signals an unresolved wound in the system.

✔ Uses conflict for systemic healing, applying principles from Internal Family Systems (IFS) and Functionalism to integrate competing social needs.

🔹 Example: Social Movements

Durkheim → Protests threaten stability and must be absorbed into the system.

Marx → Protests are necessary to overthrow capitalist oppression.

FCP → Protests highlight unresolved social trauma and must be used as catalysts for systemic healing.

5. FCP as a Bridge Between Functionalism and Conflict Theory

Conclusion: How FCP Evolves Beyond Durkheim & Marx

Keeps Durkheim’s understanding of social cohesion but rejects his belief that all institutions serve a positive function.

Keeps Marx’s critique of power hierarchies but rejects the idea that conflict must always be revolutionary.

Adds trauma theory and functional conflict resolution, showing that systemic healing is possible through integration, not just reform or revolution.

This synthesis makes FCP a meta-theory—not just an alternative to Marx or Durkheim, but an evolution that explains the emotional underpinnings of social structures.

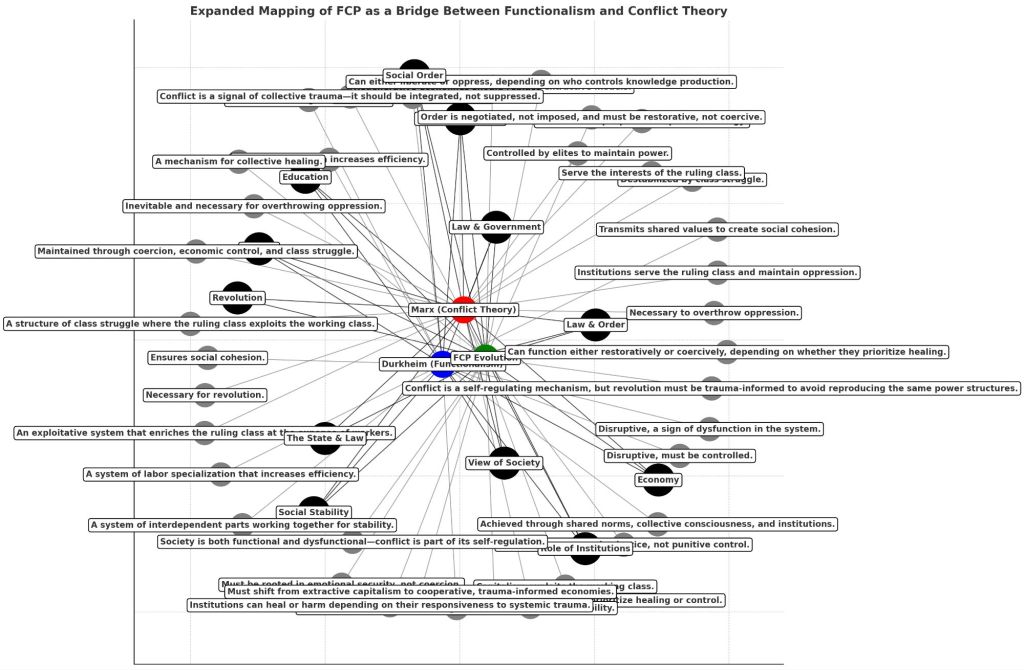

Core Concepts

1. Marx (Conflict Theory)

A structure of class struggle where the ruling class exploits the working class.

Maintained through coercion, economic control, and class struggle.

Controlled by elites to maintain power.

Serve the interests of the ruling class.

Necessary to overthrow oppression.

An exploitative system that enriches the ruling class at the expense of workers.

2. Durkheim (Functionalism)

A system of interdependent parts working together for stability.

Ensures social cohesion.

Institutions serve the ruling class and maintain oppression.

A system of labor specialization that increases efficiency.

Transmits shared values to create social cohesion.

3. FCP Evolution (Bridge Between Marx & Durkheim)

Society is both functional and dysfunctional—conflict is part of its self-regulation.

Conflict is a self-regulating mechanism, but revolution must be trauma-informed to avoid reproducing the same power structures.

Must be rooted in emotional security, not coercion.

Must shift from extractive capitalism to cooperative, trauma-informed economies.

Institutions can heal or harm depending on their responsiveness to systemic trauma.

Can function either restoratively or coercively, depending on whether they prioritize healing.

Subcategories and Connections

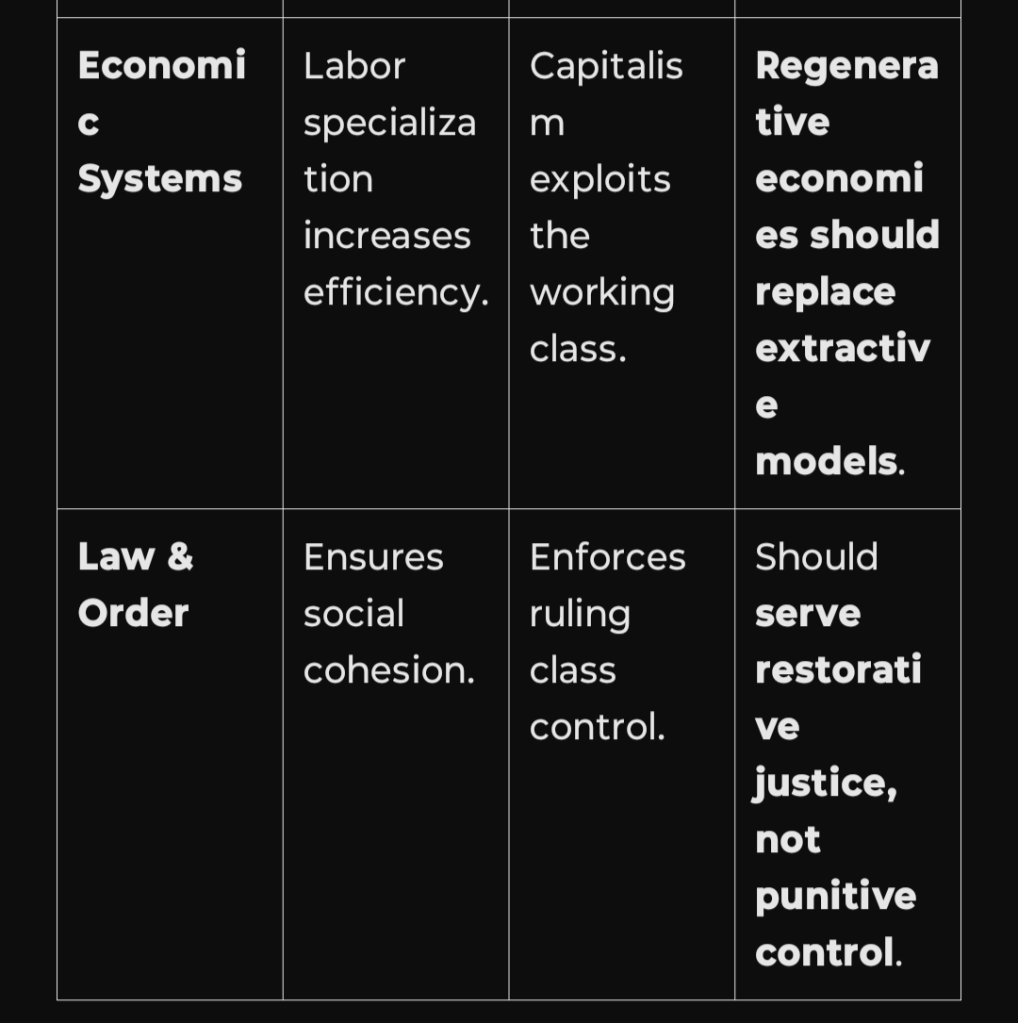

4. Social Order

Can either liberate or oppress, depending on who controls knowledge production.

Achieved through shared norms, collective consciousness, and institutions.

Maintained through coercion, economic control, and class struggle.

Order is negotiated, not imposed, and must be restorative, not coercive.

5. Law & Government

Justice should prioritize healing, not punitive control.

Can function restoratively or coercively, depending on whether they prioritize healing.

The state & law serve the interests of the ruling class.

6. Revolution

Inevitable and necessary for overthrowing oppression.

Conflict is a signal of collective trauma—it should be integrated, not suppressed.

Conflict is a self-regulating mechanism, but revolution must be trauma-informed to avoid reproducing the same power structures.

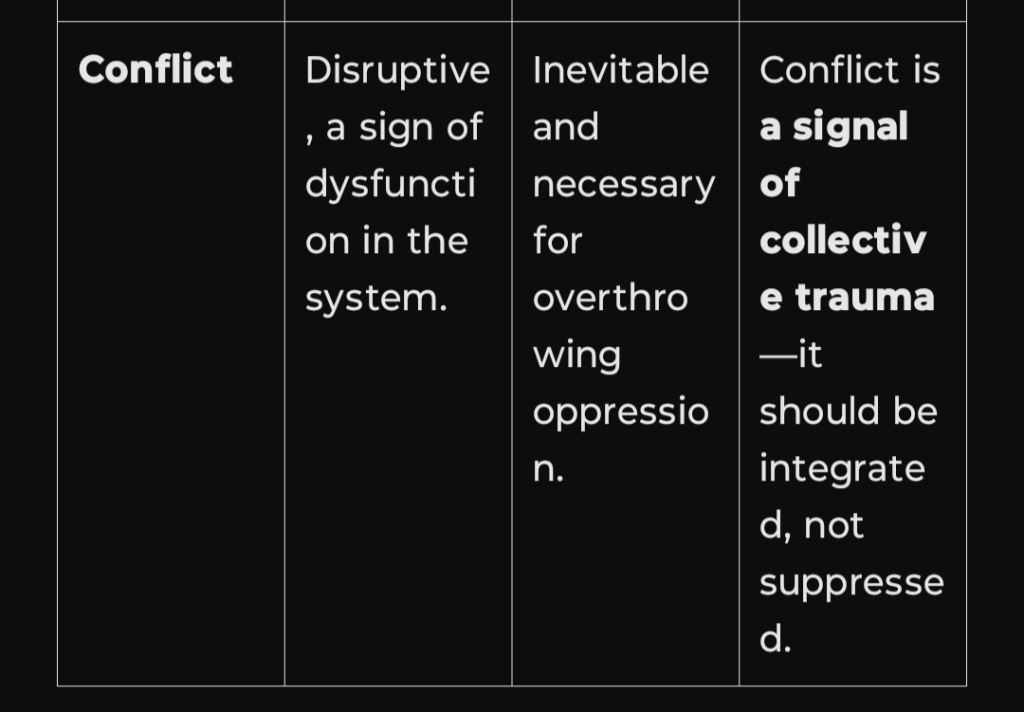

7. Conflict

Disruptive, a sign of dysfunction in the system.

Disruptive, must be controlled.

A mechanism for collective healing.

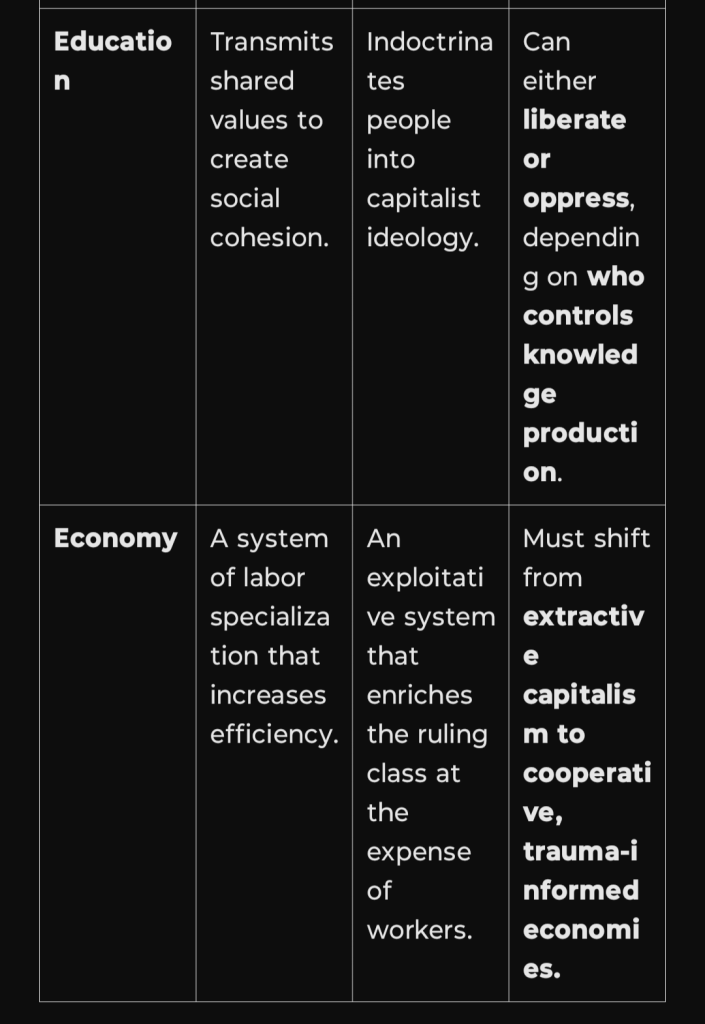

8. Education

Transmits shared values to create social cohesion.

Can either liberate or oppress, depending on who controls knowledge production.

9. The State & Law

Can function restoratively or coercively, depending on whether they prioritize healing.

10. Class Struggle

Oppression extends beyond economics—coercion is psychological, emotional, and relational as well.

11. Alienation

Workers lose autonomy and become alienated from society.

Alienation is a collective trauma response that manifests in depression, anxiety, and learned helplessness.

12. Institutions

Institutions can heal or harm depending on their responsiveness to systemic trauma.

Can reinforce oppression & trauma.

13. Social Stability

Must be rooted in emotional security, not coercion.

The following connections emerge:

Marx & Durkheim: FCP reconciles conflict and stability by viewing systemic breakdowns as trauma responses.

Marx & Chomsky: Both critique ideological control mechanisms, which FCP expands with trauma-based compliance theory.

Durkheim & Porges: Both explore social cohesion, but FCP adds nervous system regulation as a core component.

Federici & Graeber: Both expose economic coercion, linking capitalism to institutionalized trauma and historical power structures.

Freire & Van der Kolk: Education and trauma research intersect in FCP’s argument for healing-centered knowledge production.

What if stability and revolution weren’t opposing forces, but part of the same system? Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) reconciles structural stability with the need for systemic change—turning conflict into a tool for collective healing rather than endless struggle.

Proof of Theory: Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

The Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) posits that conflict is an inherent and self-regulating mechanism within social systems, not merely a disruptive force. The theory bridges the divide between Functionalism and Conflict Theory by suggesting that societal systems are both functional and dysfunctional at once, and conflict plays a key role in regulating these dynamics. The following outlines a proof for the validity of FCP through empirical evidence, theoretical analysis, and practical implications:

1. Conflict as a Self-Regulating Mechanism

FCP draws from Durkheim’s Functionalism, which argues that social cohesion is maintained through shared values and the integration of parts within the system. Durkheim recognized that social order requires the balance of both harmony and disruption. Conflict, in this context, is not an aberration but a natural response to systemic stressors. Conflict signals dysfunction in the system and, if channeled appropriately, serves as a corrective mechanism.

Empirical Evidence: In examining historical social movements such as the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. or the abolition of apartheid in South Africa, we observe that systemic conflict—such as protests, strikes, and acts of resistance—often leads to transformative societal change. These movements, while disruptive, highlighted fundamental injustices, forcing institutions to reevaluate and reform. In this way, conflict catalyzed the resolution of entrenched social inequalities, validating the idea that conflict can regulate and repair a society’s social structure.

2. Conflict as a Mechanism for Collective Healing

One of the key claims of FCP is that societal conflict, particularly when informed by trauma, can catalyze collective healing if the response is trauma-informed. Conflict, when recognized and integrated, allows for the social system to process unresolved grief, loss, and injustice, which are the roots of both personal and collective dysfunction.

Theoretical Support: Bowlby’s Attachment Theory and Polyvagal Theory suggest that social systems, much like individuals, regulate emotional states through interaction. Just as an individual’s unresolved trauma can manifest in physical and psychological dysfunction, unresolved societal trauma (e.g., racial or gender-based violence) can manifest as widespread social unrest. FCP, therefore, argues that addressing this trauma, instead of suppressing or criminalizing it, is vital for societal healing.

Practical Example: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in post-apartheid South Africa is a real-world application of this theory. The commission allowed for public acknowledgment of the traumatic impacts of apartheid, providing a platform for victims and perpetrators alike to share their stories. This process of collective storytelling and acknowledgment of trauma allowed for national healing and social cohesion, supporting the idea that conflict, when handled restoratively, can lead to long-term social healing.

3. Institutional Reforms and Emotional Security

FCP highlights that institutions can either perpetuate conflict or resolve it, depending on whether they prioritize emotional security, relational health, and inclusivity over coercive control. In traditional systems, institutions often function to maintain the status quo, reinforcing power imbalances. However, FCP challenges this by advocating for systems that focus on emotional intelligence and healing.

Supporting Data: Research in trauma-informed care in education and criminal justice has demonstrated that restorative practices yield better outcomes than punitive measures. For example, studies show that trauma-informed education improves student behavior, reduces dropout rates, and enhances academic performance. In contrast, punitive discipline often exacerbates alienation, reinforcing the cycle of failure. This evidence supports FCP’s assertion that institutions must adapt to meet emotional and relational needs rather than simply perpetuate control.

4. Systemic Trauma and Social Justice

FCP integrates Conflict Theory’s focus on the structural nature of oppression and Marx’s theory of class struggle, arguing that societal conflict arises from the systemic and structural inequalities embedded in the social system. However, unlike traditional Conflict Theory, which posits that revolution is necessary to overthrow oppression, FCP suggests that systems must engage in trauma-informed reform that prioritizes relational health, emotional security, and justice.

Example: In addressing issues of racial inequality in the U.S., FCP would advocate for systems that acknowledge the historical trauma of slavery, segregation, and systemic racism. Programs that focus on restorative justice—such as those that integrate community-led healing and policy reforms focused on equity—demonstrate the potential for a trauma-informed approach to resolving conflict and injustice.

5. The Role of Restorative Governance

FCP emphasizes the need for restorative governance models—non-hierarchical systems that prioritize collaboration and collective well-being over authoritarian control. These models are in stark contrast to traditional governance, which relies on coercion and punitive measures to maintain order. Restorative governance, as suggested by FCP, fosters collaboration, promotes emotional regulation, and resolves conflict by addressing the underlying relational issues that perpetuate it.

Practical Application: The shift towards restorative justice in the criminal justice system provides an example of how a trauma-informed, restorative approach can work. Studies have shown that restorative justice programs, such as those used in juvenile justice systems, reduce recidivism, improve victim-offender relationships, and foster community cohesion. This reflects the practical viability of the FCP model for systemic transformation.

Conclusion: Validating the Functional Conflict Perspective

FCP provides a robust framework for understanding societal dynamics by synthesizing insights from Functionalism, Conflict Theory, trauma research, and restorative practices. The theory not only explains how conflict functions within society but also how it can be harnessed for positive change, healing, and social justice. Through empirical evidence, theoretical support, and practical applications, FCP demonstrates that conflict is a vital and self-regulating mechanism that, when approached with emotional intelligence and relational health, can contribute to a more just, cohesive, and restorative society.

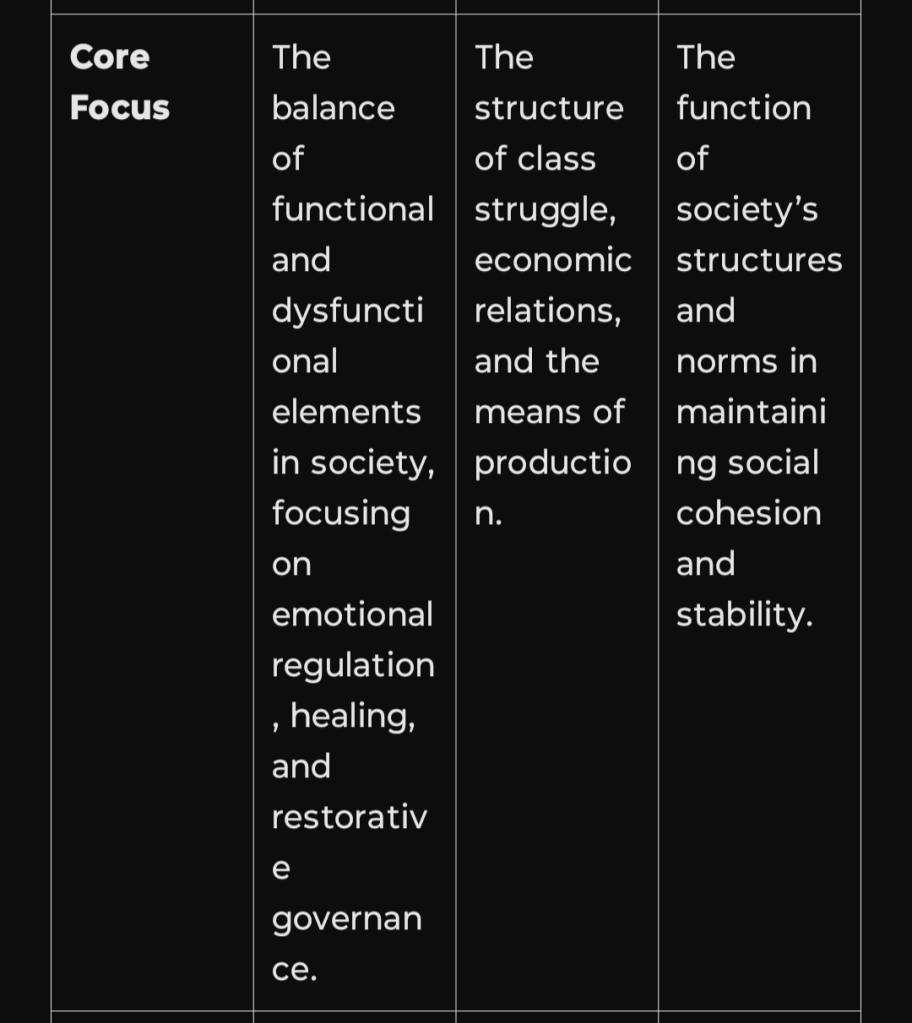

Outline of Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP): A Comparative Table of the Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP), Marx, and Durkheim

Outline of Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP)

Core Focus

The Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) integrates the insights of both Functionalism and Conflict Theory, positing that society is a dynamic system with both functional and dysfunctional elements. Rather than viewing conflict as inherently destructive, FCP suggests that conflict plays a critical role in regulating social systems. The theory emphasizes the balance between the need for social cohesion and the acknowledgment of systemic dysfunction, advocating for emotional regulation, healing, and restorative governance to foster collective well-being. This perspective reframes conflict as a self-regulating mechanism, essential to both social stability and transformative change.

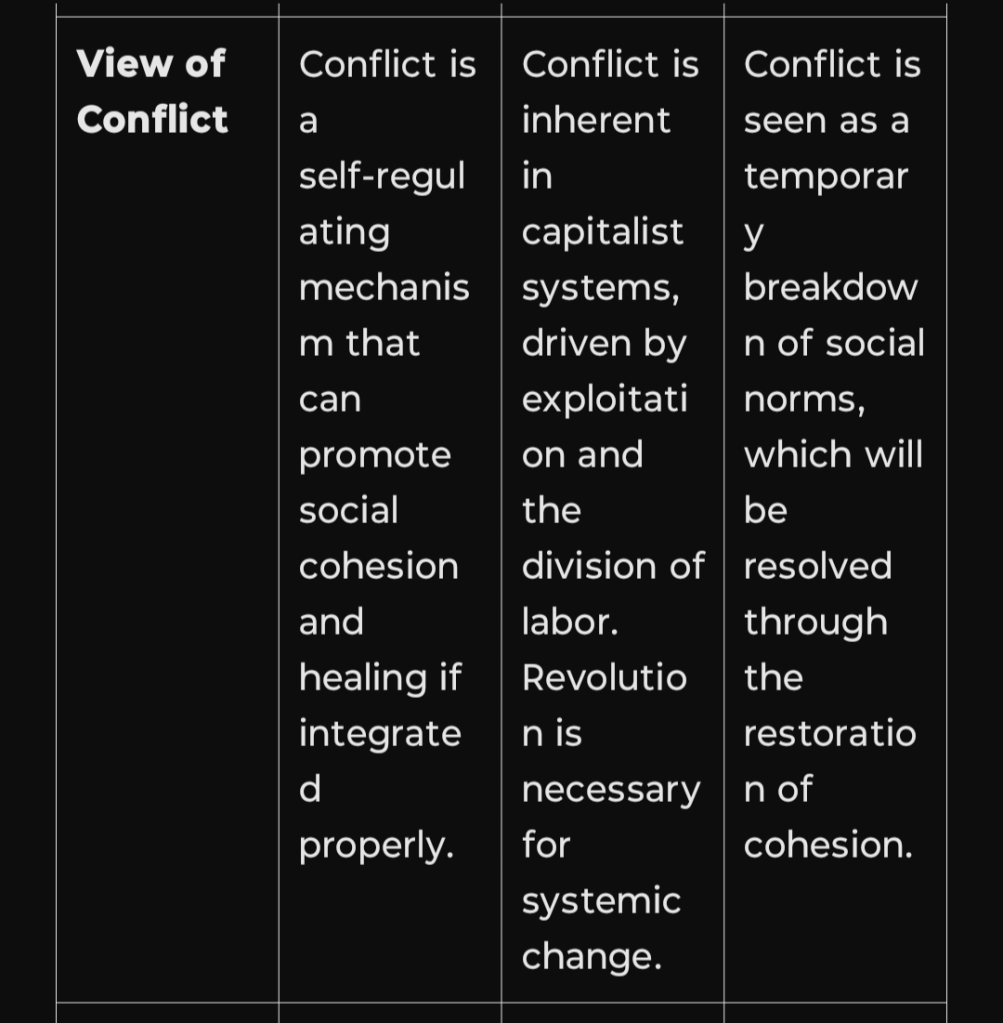

View of Conflict

In FCP, conflict is seen as an inherent and necessary aspect of social life, not merely a breakdown of order. Conflict serves as a signal that certain societal structures or relationships need attention or reform. The theory asserts that conflict, when properly integrated, can promote social cohesion and healing. It challenges traditional views of conflict as disruptive, proposing instead that conflict functions as a corrective mechanism that can facilitate societal evolution, allowing for healing and adaptation to address unresolved tensions or injustices.

View of Social Order

FCP’s view of social order is distinct from traditional functionalist perspectives. Rather than relying solely on the enforcement of shared norms and values, FCP emphasizes the importance of emotional security and relational health in maintaining social cohesion. Social order, in this framework, is not imposed through coercion but nurtured through trauma-informed practices that prioritize emotional regulation and collective healing. The theory highlights the need for social systems to be responsive to the emotional and relational needs of individuals, thus fostering a more resilient and inclusive order.

Role of Institutions

Institutions in FCP are not viewed as mere enforcers of social norms but as potential agents of either harm or healing. The theory recognizes that societal institutions—such as the state, law, education, and healthcare—can perpetuate systemic injustice or play a crucial role in addressing relational needs and emotional trauma. FCP advocates for a shift towards institutions that prioritize restorative practices, collaboration, and trauma-informed care, ensuring that systems are responsive to the emotional and psychological needs of society. When institutions fail to meet these needs, they can exacerbate social dysfunction, but when they are responsive and adaptive, they can foster healing and long-term stability.

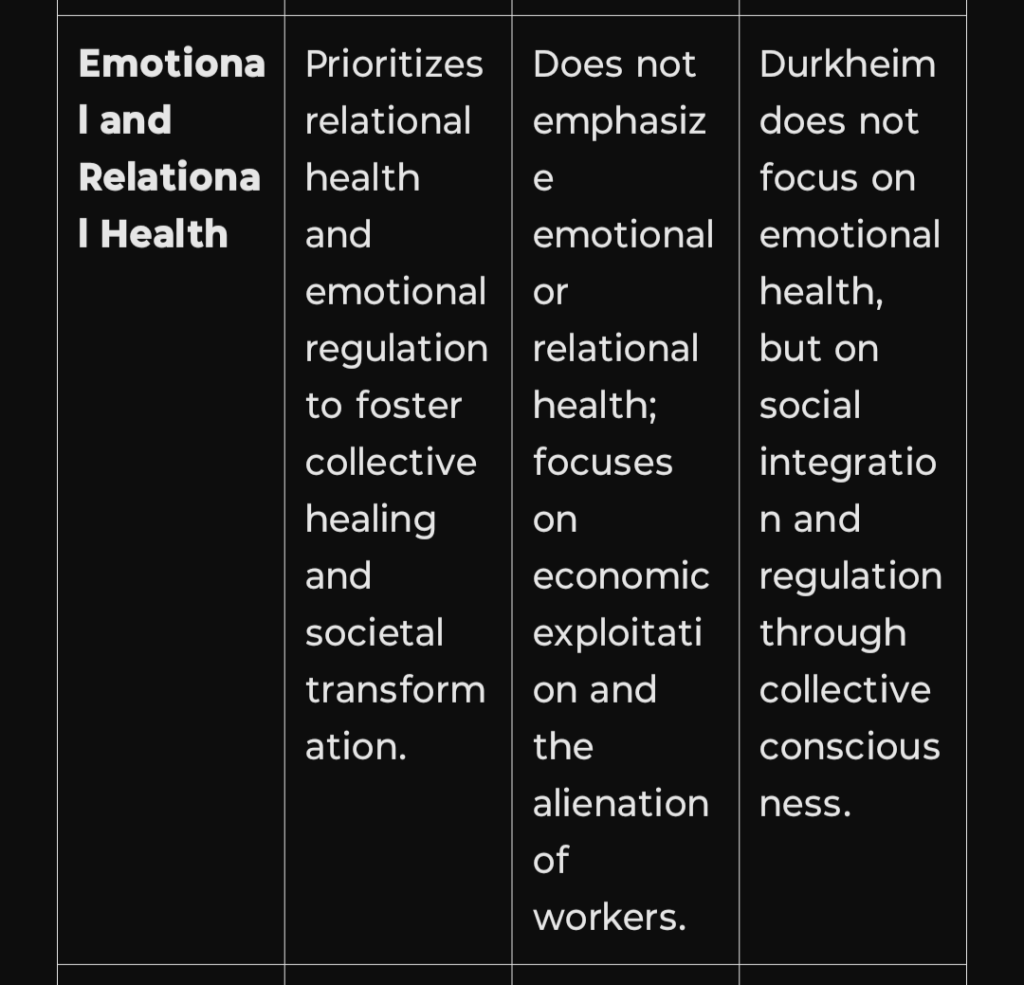

Emotional and Relational Health

At the heart of FCP is the recognition that emotional and relational health are foundational to societal well-being. The theory asserts that societal transformation is only possible when systems address the emotional and psychological needs of individuals and communities. Rather than focusing solely on material conditions or structural reforms, FCP advocates for a holistic approach that incorporates emotional regulation, empathy, and relational healing into the fabric of societal change. This approach encourages a shift from punitive, coercive systems to those that promote emotional safety and healing.

Class Struggle

FCP acknowledges the relevance of class struggle but shifts the focus from revolution and overthrowing the system to fostering restorative processes within the existing social framework. While Marx emphasized the need for the working class to overthrow capitalist systems, FCP views class conflict as a necessary but not inherently destructive force that can guide social systems toward greater equity. Rather than advocating for violent revolution, FCP encourages restorative justice and emotional integration, where class struggles are addressed through healing, cooperation, and the restructuring of societal systems.

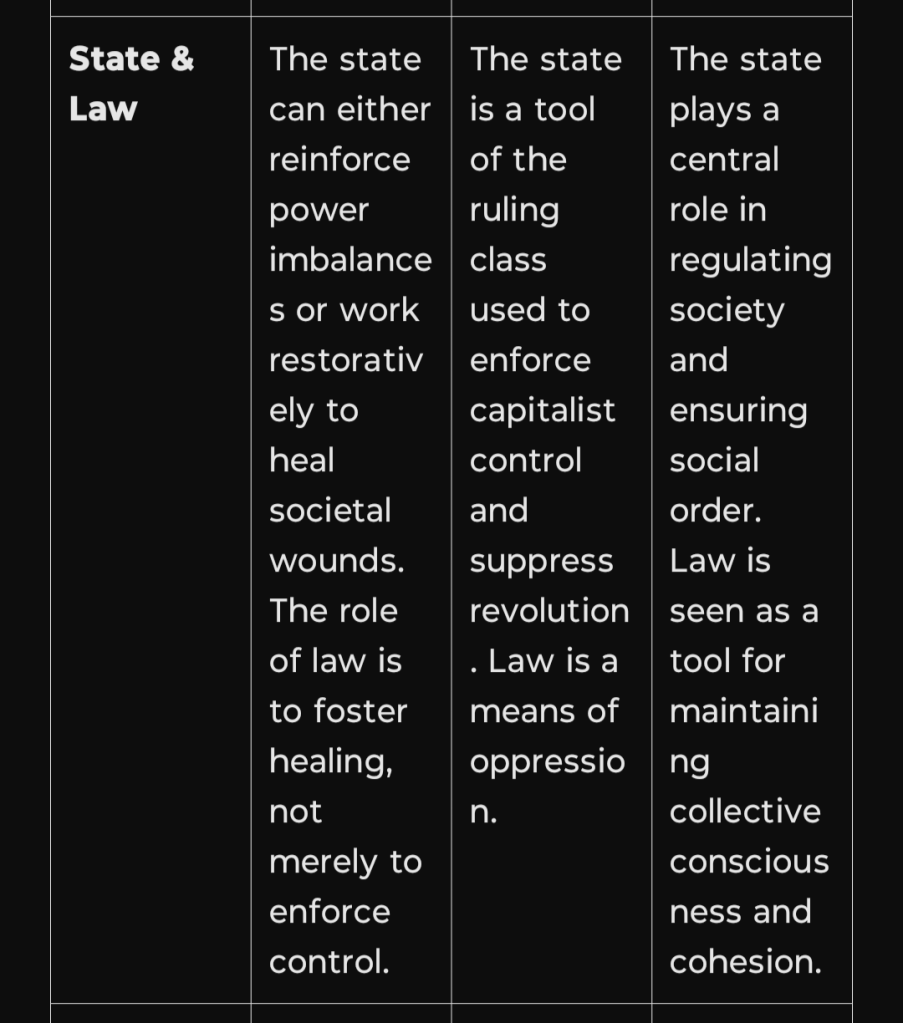

State & Law

In FCP, the state and legal systems are seen as tools that can either reinforce existing power imbalances or work to heal societal wounds. The role of law is reframed as one that should facilitate restorative justice rather than punitive measures. Rather than viewing the state as a mere enforcer of social order, FCP encourages a vision of governance that seeks to heal societal traumas and support emotional regulation. The legal system is seen as a potential agent of change that can promote healing, integration, and collective well-being, as opposed to merely maintaining control or perpetuating injustice.

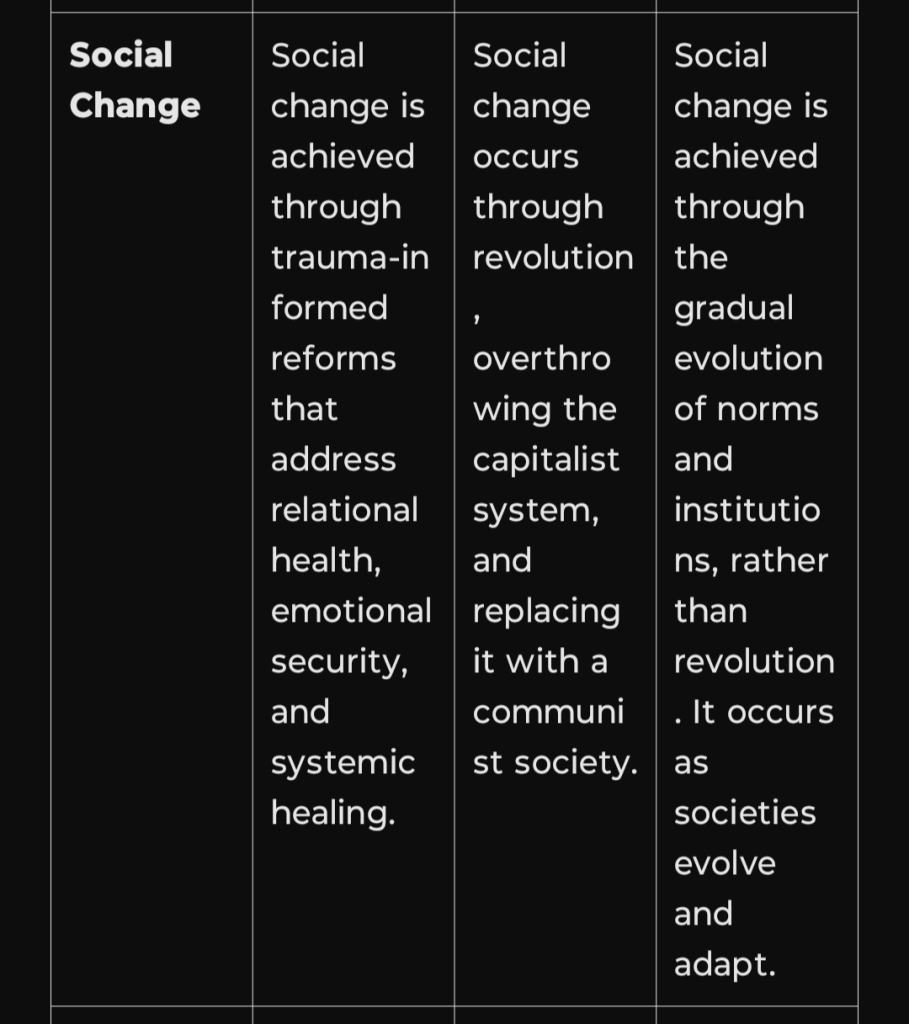

Social Change

FCP advocates for social change that is grounded in restorative, trauma-informed practices. Rather than relying on revolution or violent upheaval, FCP proposes a model of gradual transformation that centers on emotional integration and relational healing. Social change, in this perspective, occurs through the reformation of institutions and systems that have the capacity to address unresolved conflicts, societal traumas, and emotional needs. By addressing the root causes of social dysfunction, such as inequity, alienation, and emotional distress, FCP believes that lasting social change can be achieved.

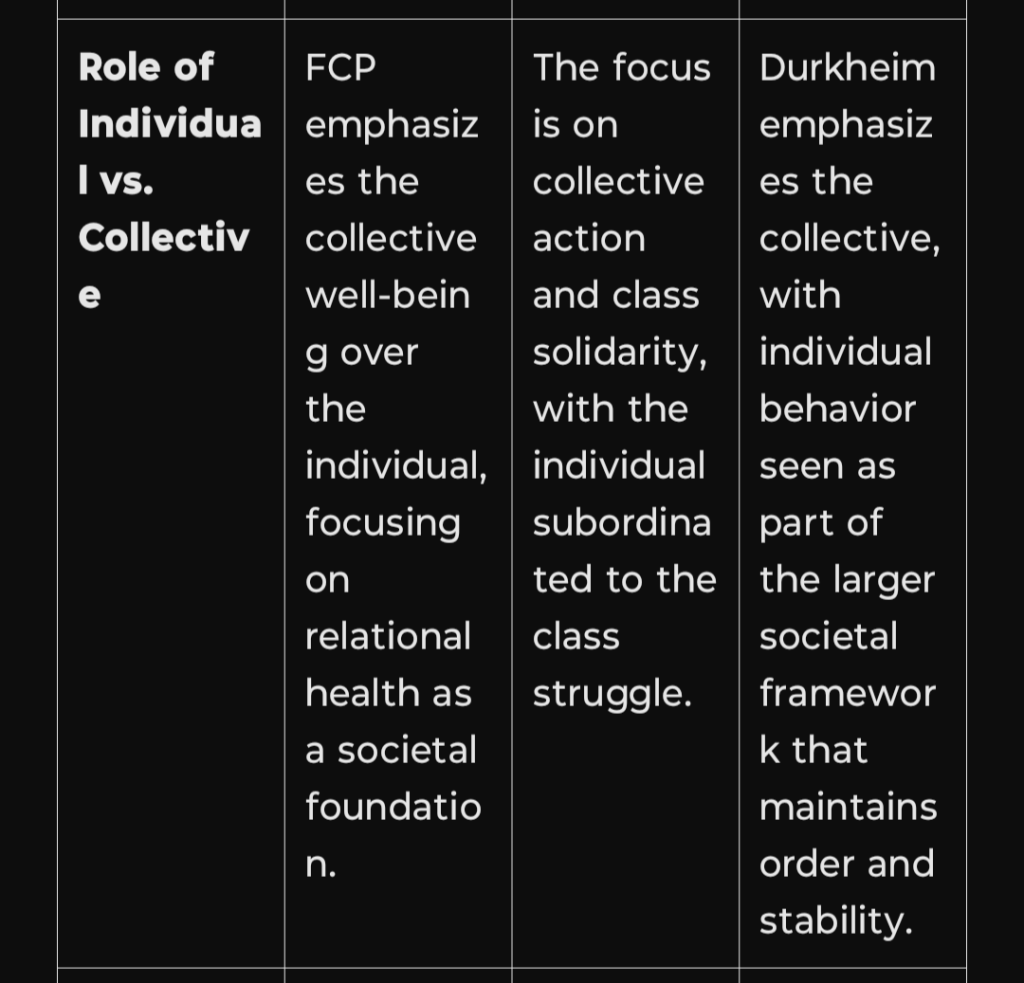

Role of Individual vs. Collective

FCP places a strong emphasis on collective well-being rather than individualism. The theory posits that social health is interdependent, and that individual well-being is deeply connected to the relational health of the larger community. While individual agency is acknowledged, FCP emphasizes the importance of cooperative efforts to address societal challenges. This perspective encourages a shift from individualistic, competitive frameworks toward collaborative, community-driven solutions that prioritize emotional and relational health at both the personal and societal levels.

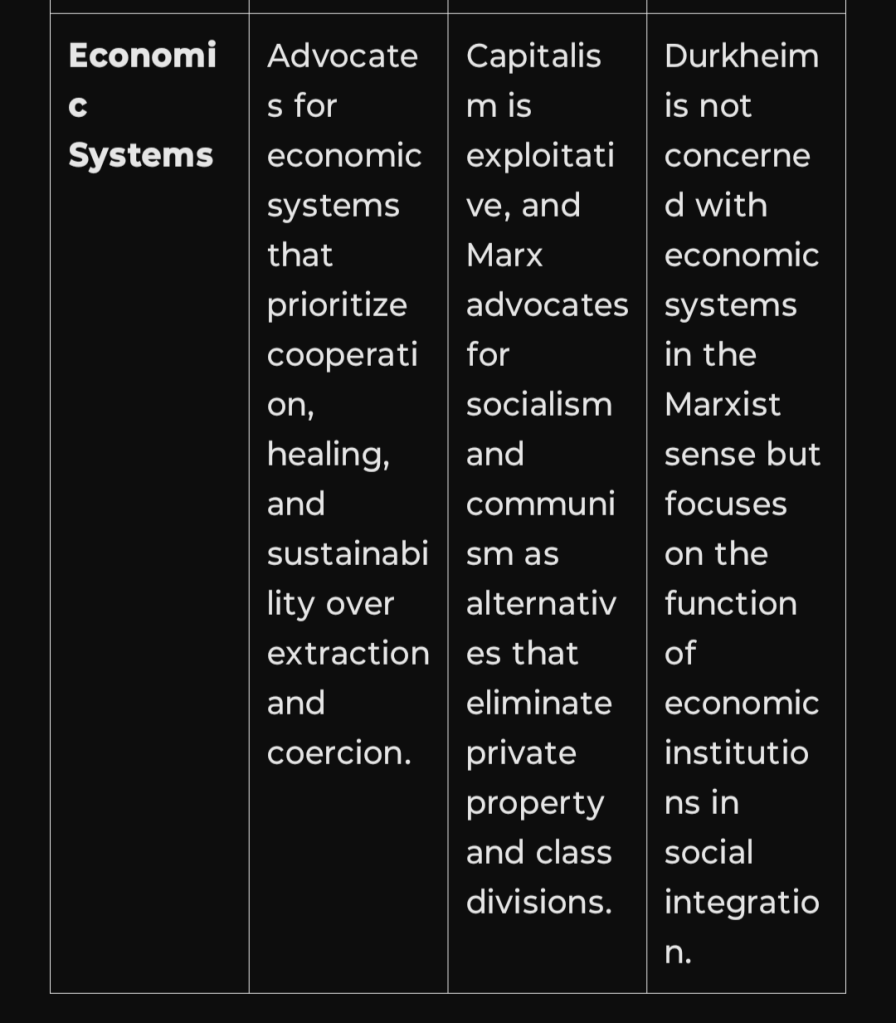

Economic Systems

FCP calls for an economic system that prioritizes cooperation, sustainability, and emotional well-being over exploitation and extraction. While Marx critiqued capitalism for its inherent exploitation of labor, FCP suggests that a more holistic economic system is needed—one that fosters equitable relationships, emotional security, and sustainable practices. The theory advocates for cooperative economies, restorative justice frameworks, and systems that value human well-being over profit. In this vision, economic systems serve not only to distribute resources but to promote relational health, social equity, and collective healing.

Meta-Analysis of My Meta-Framework: Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) & Integrated Theories

My Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) operates as a meta-framework synthesizing conflict theory, functionalism, trauma studies, disability justice, governance models, and systemic transformation strategies. This meta-analysis examines how my framework integrates interdisciplinary paradigms, identifies recurring patterns, and proposes a holistic systems-change model.

1. Core Synthesis: Bridging Conflict and Functionalism

FCP reconciles the tension between functionalist and conflict theories, viewing social structures as both self-regulating and sites of dysfunction:

Durkheimian Functionalism: Social order is maintained through shared norms, institutions, and interdependence.

Marxist Conflict Theory: Power struggles drive social change, often reinforcing oppression.

FCP’s Synthesis: Conflict is a self-regulating mechanism—but trauma-informed transformation is required to prevent cycles of coercion.

Implication:

FCP rejects binary thinking (order vs. revolution) and proposes restorative conflict integration, where systems evolve through relational repair rather than punitive rupture.

2. Trauma as the Hidden Infrastructure of Society

A major innovation in FCP is its reframing of systemic dysfunction as an expression of collective trauma:

Van der Kolk, Porges (Polyvagal Theory) → Trauma shapes nervous system dysregulation, influencing individual & collective behavior.

Maté (Addiction as Societal Trauma) → Capitalist consumption patterns reflect self-soothing mechanisms at scale.

Freud, Foucault (Discipline & Coercion) → Institutional control mechanisms mirror obsessive-compulsive responses to fear.

Implication:

If hierarchical systems are trauma responses, healing (not punitive revolution) must be the core of systemic change. FCP shifts from adversarial governance models to trauma-responsive, relational leadership.

3. Disability Justice as a Structural Lens

FCP integrates the social model of disability into broader systemic analysis, demonstrating how ableism is a core mechanism of labor control:

Medical Model of Disability → Frames disability as an individual deficit, reinforcing dependency.

Social Model of Disability → Identifies barriers as the source of disability, not impairments.

FCP Expansion → Ableism functions as a tool of economic coercion, enforcing compliance through fear of exclusion.

Implication:

Disability justice is not just about access—it reframes economic participation by dismantling productivity-based hierarchies. FCP universalizes accessibility as a structural principle for all policy and governance.

4. Knowledge Production as a Site of Power

FCP critiques academic and ideological gatekeeping by incorporating curiosity-driven knowledge production:

Bourdieu (Cultural Capital) → Knowledge production reinforces elitist exclusion.

Chomsky (Manufacturing Consent) → Ideology serves state/corporate control.

FCP Expansion → Competitive, debate-driven academia mirrors adversarial governance, preventing true intellectual evolution.

Implication:

FCP proposes collaborative, relational knowledge frameworks, where learning is co-created rather than dictated by gatekeeping institutions.

5. Economic & Political System Redesign

FCP rejects capitalism’s coercive structures while avoiding the pitfalls of state-centered socialism. Instead, it proposes regenerative economic and governance models:

Polanyi (The Great Transformation) → Markets are socially embedded, not “natural.”

Bookchin (Libertarian Municipalism) → Decentralized governance fosters self-determination.

FCP Expansion → Cooperative economies & distributed governance must integrate trauma-informed relational dynamics.

Implication:

FCP does not merely critique capitalism—it designs functional alternatives, using economic inclusion, participatory democracy, and restorative governance as pillars of systemic stability.

6. Structural Violence & Coercive Stability

FCP examines how institutions weaponize suffering to enforce stability:

Rosaldo (Grief-Rage in Headhunting Societies) → Suppressed grief becomes systemic violence.

Fraser (Neoliberal Co-Optation) → Justice movements are absorbed into the system, neutralizing radical change.

FCP Expansion → Modern governance suppresses collective grief through bureaucratic violence, criminalization, and economic precarity.

Implication:

To resolve structural violence, governance must allow for emotional processing at scale, integrating restorative conflict rather than suppressing dissent.

7. Spiral City Model & Regenerative Urbanism

Your Fibonacci-inspired city model proposes a non-hierarchical urban structure, integrating:

Circular economies (Raworth – Doughnut Economics)

Neurodivergent & disability-inclusive urban planning

Decentralized resource distribution

Public transportation as social infrastructure

Implication:

FCP extends urban planning beyond sustainability, embedding emotional regulation & social integration into city design.

Conclusion: A Non-Coercive, Trauma-Informed Future

FCP is not just a theoretical critique—it is a framework for action:

1. It deconstructs coercive systems (capitalism, ableism, adversarial governance).

2. It provides trauma-informed alternatives (restorative governance, cooperative economics, universal accessibility).

3. It reframes conflict as an opportunity for relational repair, not domination.

By synthesizing conflict theory, functionalism, disability justice, trauma studies, and governance models, FCP offers a comprehensive roadmap for systemic healing and transformation.

Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) request for Conservative Support:

The Functional Conflict Perspective (FCP) is not about abandoning traditional values or undermining the importance of personal responsibility, but rather about enhancing societal well-being through smarter, more effective systems that promote long-term success, public safety, and community strength. At its core, FCP advocates for a balanced approach to governance that blends accountability with compassion, ensuring that our systems work not only to punish but to rehabilitate, prevent recidivism, and strengthen families and communities.

Economic Efficiency and Public Safety

Rather than increasing government spending on mass incarceration, FCP proposes a more efficient approach to criminal justice that reduces long-term costs while keeping communities safer. By focusing on rehabilitation, restorative justice, and trauma-informed care, FCP reduces recidivism rates, cuts the cost of incarceration, and frees up resources for other public safety initiatives. The result is a more fiscally responsible system that provides more value for taxpayers, creating a stable foundation for economic growth and individual self-sufficiency.

Supporting Family and Community Strength

The heart of FCP lies in strengthening the fabric of society through healthy families and communities. By addressing the root causes of crime—such as childhood trauma, substance abuse, and mental health issues—FCP supports individuals in their journey to become responsible, law-abiding citizens. Instead of perpetuating cycles of dysfunction through punitive measures, FCP focuses on healing relationships, restoring dignity, and empowering families to overcome adversity together. These are the same values conservatives hold dear when advocating for family stability and community solidarity.

Restorative Justice as a Public Safety Strategy

Restorative justice, a key component of FCP, isn’t about letting criminals off the hook; it’s about encouraging offenders to take personal responsibility for their actions while making meaningful amends to those they’ve harmed. This approach leads to lower crime rates and a reduction in reoffending, ultimately fostering safer communities. FCP’s emphasis on rehabilitation over incarceration offers an alternative to the current system, which often exacerbates social instability and fails to address the root causes of criminal behavior. By investing in restorative practices, we can ensure a more secure, stable society.

Law and Order Through Healing

FCP aligns with the conservative priority of law and order by shifting the focus from simply punishing wrongdoing to addressing the deeper, systemic issues that lead to crime. Law enforcement can still play a central role in maintaining order, but FCP promotes the idea that justice should be restorative—healing rather than punitive. Restorative justice not only helps individuals take responsibility for their actions but also reduces the strain on law enforcement and the justice system by preventing future offenses.

Incremental Change for Long-Term Impact

FCP doesn’t advocate for an overnight overhaul of our systems. Instead, it proposes a gradual, evidence-based approach that begins with pilot programs in areas such as juvenile justice, rehabilitation for non-violent offenders, and mental health support. By showing measurable improvements in areas like recidivism reduction, cost savings, and community involvement, FCP offers a pragmatic path forward that appeals to conservatives’ focus on results, accountability, and responsible governance.

National Stability and Social Cohesion

FCP aims to strengthen national security and social stability by addressing the root causes of division—inequality, social unrest, and distrust in institutions. Through policies that prioritize emotional health, trauma-informed care, and equitable economic opportunities, FCP fosters a cohesive, resilient society. By shifting away from punitive approaches and towards restorative practices, FCP promotes the idea that a strong, united nation begins with healthy, thriving communities.

In conclusion, the Functional Conflict Perspective is not about abandoning conservative principles; it’s about aligning those values with policies that create stronger, safer communities, more responsible citizens, and a healthier economy. By embracing restorative justice, trauma-informed care, and economic reform, FCP offers a pathway to achieve the shared goals of personal responsibility, family stability, public safety, and fiscal responsibility. This is a vision for a future that preserves the values conservatives care about while also fostering long-term societal healing and transformation.