Isha Sarah Snow

Lower Columbia College

pandemicnova@gmail.com

17997 total word count

ABSTRACT:

Using punitive discipline methods results in lower levels of cognitive complexity, which is how well people perceive things. Low cognitive complexity results in difficulties with self control and emotional self regulation, which show up in adulthood as deviant behavior, such as impulsivity and aggression. Deviance is any behavior or reaction that lies outside of social norms. This research project focuses on socio-emotional deviant behaviors which fail to conform to society’s norms and expectations, such as aggression and low impulse control. This research compiled qualitative data from five interview subjects who represent a range of ages, genders, and races, and analyzed the information, concluding that experiencing supportive correction in the form of connection, empathy and understanding alongside clear and direct communication during childhood mitigated potential difficulties with emotional regulation in adulthood.

This research project connects attachment theory with situational control theory, providing a valuable link between the fields of psychology and sociology, and its findings offer a potential solution to mitigating and preventing deviant behaviors resulting from difficulties with emotional regulation, which can be seen in society today. The literature review contains the topics of parent imprinting and role modeling, attachment and communication theories (or a lack of imprinting and positive role models), the role emotion plays in development and how it is stifled by insecure attachment, ways that fear can impact learning and development, Adverse Childhood Experiences, social and moral integration, and the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

Keywords: attachment, discipline, behavior, communication, parenting, prefrontal cortex, cognitive complexity

THESIS:

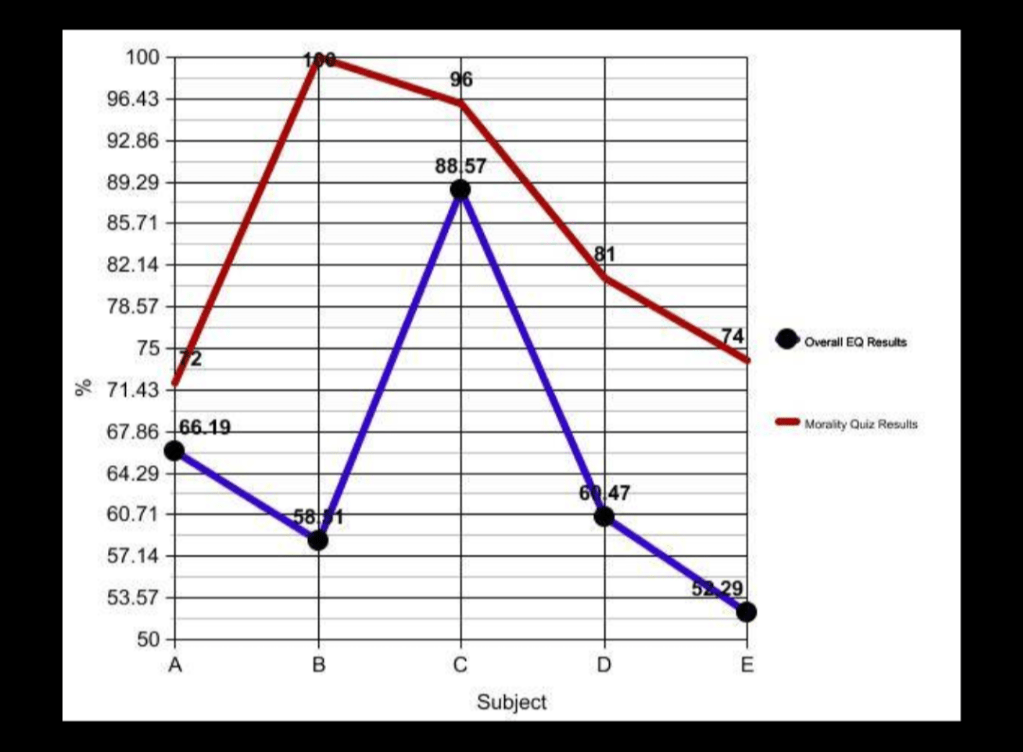

It is well documented that the ways parents and caregivers communicate with their children affect a child’s abilities to empathize. Using punitive discipline methods can damage or arrest development to the prefrontal cortex. Childhood symptomatology appears as difficulties with self control and emotional self regulation, and in adulthood, impulsivity and aggression. Prefrontal cortex functionality through cognitive complexity can be measured by evaluating an individual’s differences between their tested morality and emotional intelligence scores.

I chose the topic of generational trauma and the different types of communication associated with various attachment styles in order to study how different methods of childhood discipline could potentially correlate with adult behavior patterns. This study is based on research that I performed independently following my own trauma recovery after separation from a dysfunctional family system, and thus a personal bias was potentially introduced to the study in the initial topic choice. The research for this paper and study was gathered with this bias in mind and an effort was made to be objective and remain detached from the outcome and the process. That was done by attempting to not influence my subjects’ answers in any way, even when prompting them to provide further clarifying information. It is believed that the data gathered from all five subjects of various ages and genders is an accurate representation of what the findings would be among similar individuals outside of this research project. Further in depth research on this topic would certainly be recommended, and would be supported by the results of this study.

LITERATURE REVIEW:

Modeling emotional regulation, boundaries and conflict resolution creates children who feel heard and listened to, who will feel confident to advocate for their needs while trusting those needs will be met or at least taken into consideration and negotiated fairly. Vulnerable children who are not given this security in their attachments with their primary caregivers suffer tragic consequences from their parent’s lack of ability to lead with empathy and integrity. “There is more and more evidence that dissociation is caused by dysfunctional attachment – you don’t have somebody who looks at you and picks you up and responds to you when you are in distress, so you learn to deal with your misery by shutting yourself down,” said Bessel van der Kolk, M.D. (Van Der Kolk, 2015). Dr. Gordon Neufeld of the Neufeld Institute said that “Emotion, long dismissed as a nuisance factor, is now confirmed to be at the core of development and well being. Yet little is being taught about the nature of emotion or the implications for parenting, teaching, and treatment. To make sense of emotion is to make sense of us all. There is no better way to glean insight into oneself and others than through a working knowledge of the science of emotion.” (Maté and Neufeld, 2019) In a recent podcast, Gabor Maté said “We use this word discipline, but what does the word discipline actually mean? We think it means punishment. No, it doesn’t. Who had disciples? Jesus, for example, had disciples. Not because he punished or threatened them, but because he loved them and they loved him. So then naturally they wanted to learn more from him.” (Lansbury and Maté, 2024)

Methods of parenting typically vary from generation to generation, especially when it comes to discipline. While this is normal, it does not necessarily mean that these patterns are beneficial to repeat. This research paper will clarify which parenting styles are least and most beneficial for a child’s development into a fully individuated adult, with appropriately developed morals and the ability to act on them. Mimicking or mirroring others is the first step in the development of a separate sense of self (Mead, 1934) and when children are cared for by adults lacking in cognitive complexity, they are unable to fully individuate. Cognitive complexity is the ability to construct a variety of different frameworks for viewing any issue (Adler and Proctor, 2017). Parents’ approach to discipline, their family communication styles (Model A) and individual attachment styles (Model B) all impact their child’s development of both empathy and cognitive complexity. In other words, parents can apply their own egocentric influences on their child’s ability to perspective shift (Burleson, et al., 1995). Parents’ communication styles also have a powerful effect on a child’s development in general. A study by John Gottman has shown that there are two separate styles of parenting: “emotion coaching” and “emotion dismissing” (Gottman et al., 2013), with the coaching approach giving children the skills they need for communicating their feelings in adulthood. Children who grew up in dismissing families have an elevated risk of developing behavior problems as they mature (Lunkenheimer et. al., 2007). Studies show a connection between cognitive complexity and empathy (Joireman, 2004). Research also shows that people who live in individualist cultures lack cognitive complexity, as opposed to collectivist cultures who are more skilled at perspective taking, because those cultures require greater attunement to each other.

Evidence suggests that this deficit in cognitive complexity manifests itself as an egocentric interference to the thought process. In other words, individualistic Western cultures create in its members an inability to empathize due to this culturally ingrained egocentrism (Triandis et al., 1988; Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Ross et al., 2002) with one study concluding “lifelong membership in a particular culture may shape one’s tendency or ability to take another’s perspective into account while comprehending language” (Wu et al., 2013). It is important to note that this egocentric interference is unique to Western, meaning European and North American, culture (Wu and Keysar, 2007). There is still good news for Westerners: cognitive complexity is a skill which can be developed and enhanced through practicing viewing issues from multiple sides. A group of Japanese children developed the Pillow Method, called such because it views every conflict or communication issue as having four sides and a center just like a pillow. These consist of: “I’m right and you’re wrong (side 1)”; “you’re right and I’m wrong (side 2)”; “we are both right and both are wrong (side 3)”; “the issue isn’t important to us (side 4)”; “there is truth in all perspectives (center)”. This exercise takes effort and time to pause and consider a problem before responding as opposed to simply reacting, but after repeated use will train the brain to be able to quickly switch perspectives. The pillow method enables people to see the flaws in their own thinking as well as see the merits of other perspectives. Cognitive complexity relates to higher levels of emotional intelligence, and is a measure of how well an individual can intuitively understand information. Emotional intelligence (EQ) is the ability to perceive, express, and regulate emotions. Research has shown that trauma can disrupt a child’s ability to regulate their emotions, lowering their emotional intelligence. (Lang, 2022, page 243)

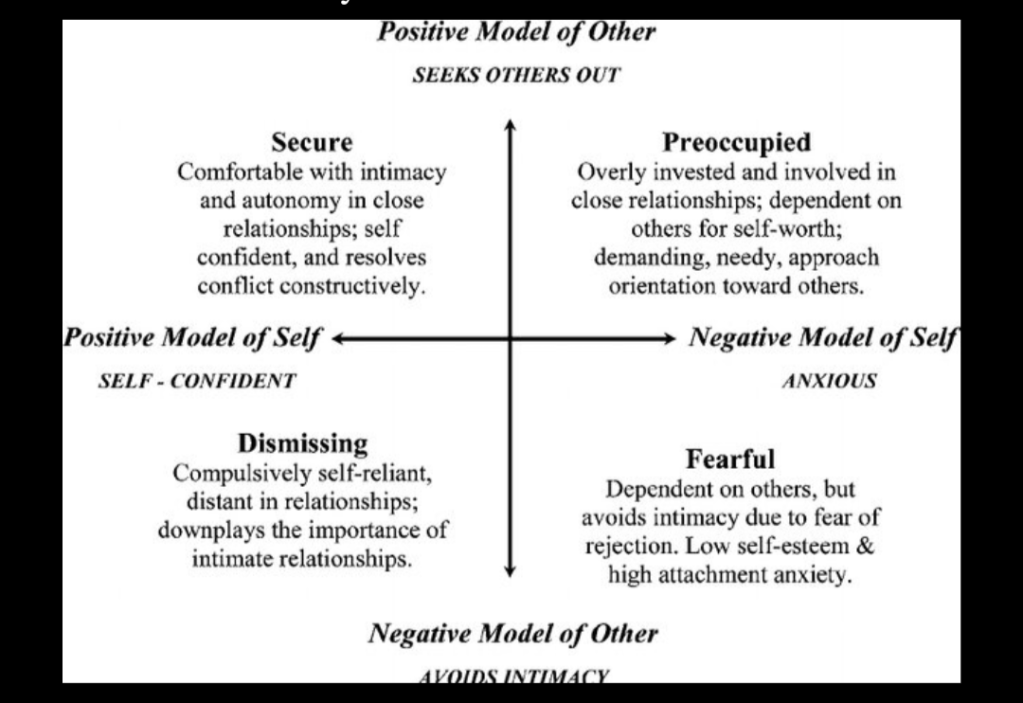

Attachment Theory, created by John Bowlby in 1982, focuses on connection being our earliest need in infancy as a survival mechanism (Model B). This goes on to form the basis of all adult relationships (Simon and Baxter, 1993). Insecure partners are more likely to act in ways that increase their odds that their insecurities will become manifest in a self fulfilling repetitive cycle (Fowler and Dillow, 2011). Healthy families emphasize interdependence, where everyone involved is able to maintain their sense of self while still depending on each other, and respect the autonomy of all individuals present, regardless of age or maturity level. They rely on trust and two way reciprocity, absent in traditional parenting and punitive discipline methods. They also rest on a firm foundation of cooperation and seek to correct behaviors through open dialogue, because “a sense of connection is what leads to compliance” (Adler and Proctor, 2017). This is sometimes referred to as “positive parenting” “attachment parenting” “gentle parenting” or “modern parenting” interchangeably, but what these terms all have in common is that these methods foster individual self reliance in children by respecting their individuality. This paper will be referring to non-traditional parenting as “supportive parenting”, due to how these methods focus on creating a loving atmosphere that prioritizes maintaining the emotional connection and bond between caregiver and child. “Open communication and shared decision making produces better results than power plays and refusal to have an open dialogue” (Adler and Proctor, 2017).

Supportive parenting creates secure attachment, which results in grown adults who are able to communicate clearly, share healthy intimacy, and maintain effective relationships with others (Shochet et al., 2007). When both partners in romantic relationships have a secure attachment style, they are able to move through conflict by communicating constructively (Domingue and Mollen, 2009). Children who grow up with disruptions to their attachment bonds tend to be more anxious and have less social skills in adulthood (Thompson and Trice-Black, 2012) and are more likely to act aggressively themselves (Wahl et al., 2012).

William Makepeace Thackeray said that “Mother is the name for God in the lips and hearts of all children.” Traditional Western parenting practices are based on systems of imposed hierarchy, which view parents as the ultimate authorities in the home who utilize coercive methods of punishments and consequences. Limits are set by authority figures and enforced through power and coercion in order to control the child in lieu of parents modeling and teaching self control. Imposed hierarchy leads to insecure attachment, RAD, and ACEs. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is a term coined in 1995 from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and household challenges, and their long term impacts on adult health and well-being (Centers for Disease Control, 2023). ACEs leave a lasting mark on a child’s forming brain and nervous system and they will result in insecure attachment and reactive attachment disorders (RAD), which are characterized by a fear based bond with caregivers created through punitive discipline and inconsistent or intermittent supportive reinforcement. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP, 2023), RAD forms as a result of negative experiences with adults in a child’s early years. In the vast majority of cases, RAD exists alongside all neurological disorders. These include mood and personality disorders, and deviant behaviors such as demand avoidance and refusal to obey rules which are commonly associated with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Demand avoidance and a refusal to comply and obey authority figures arises due to an early disruption in the bond between a child and their caregiver. A lack of emotional safety creates a psychological crisis, which results in an inability to trust caregivers to meet their needs, and disconnects the child from their attachment figure (s). The recent study Parent Grandiose Narcissism and Child Socio-Emotional Well Being: The Role of Parenting states in its abstract that “Negative parenting tactics intervened in relations between facets of…[a] child internalizing and externalizing [their emotions]” (Rawn, et. al, 2023).

The most widely used parent training programs available today and ones most utilized by social service workers include Positive Parenting (Triple P), Love and Logic, and the Incredible Years programs. They all rely on a parenting philosophy of imposed hierarchy, which is rooted in socially accepted and condoned coercive control methods. Behavioral parent training (BPT) techniques generally consist of training parents in the use of reward and punishment following appropriate and inappropriate behaviors (Behavioral Parenting Training). However, coercive rewards are still punishments, and promote extrinsic motivation over intrinsic motivation.“Behaviorism in education, or behavioral learning theory is a branch of psychology that focuses on how people learn through their interactions with the environment. It is based on the idea that all behaviors are acquired through conditioning, which is a process of reinforcement and punishment. According to this theory, learning is a change in observable behavior that results from experience.” (National University, 2023) Behaviorism undermines both relational and mental health. If the option to control is removed, what is left is figuring out how to work with children collaboratively through non-coercion, connection, collaboration, safety, trust, consent, autonomy, kindness and compassion.

Relationships are the most powerful tool for change.

Yuval Noah Harari (2015) said in his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind that “Most mammals emerge from the womb like glazed earthenware emerging from a kiln – any attempt at remoulding will only scratch or break them. Humans emerge from the womb like molten glass from a furnace. They can be spun, stretched, and shaped with a surprising degree of freedom. This is why today we can educate our children to become Christian or Buddhist, capitalist or socialist, warlike or peace-loving.” Jane Addams (1961), founder of the Hull House and the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, believed that society can be changed through effort. This research project shows that society could potentially change the way that it works by changing the ways it parents its children. Instances of deviance and demand avoidance which lead to incarcerations can be dramatically reduced by educating parents about reasonable age appropriate limits and teaching them how to create and enforce consistent consequences through the use of positive reinforcement. In a study on Early Growth and Development following 360 adopted children whose biological parents exhibited psychopathy, significantly fewer behavioral problems were experienced when their adoptive parents used more structured [supportive] parenting, as opposed to unstructured. (Leve, et. al., 2010) Focusing on connection over correction markedly reduces the intensity and frequency of hostile and defiant behaviors, and shifts the relationship dynamic from “them vs me” to a more cognitively complex “us and we,” which creates trust and a sense of emotional and psychological safety. This shift to more positive parenting practices could potentially result in a more moral society, children with a functional internal guidance system, reformation of our justice system, and ultimately a conscious shift away from imposed hierarchical authoritarian systems of government which control their populations through methods of fear and coercion. Aasi Tahir Siddique said that “If we are serious about bringing effective behavioral changes to adopt a peaceful life then it must begin long before an unborn becomes a victim of the cycle of socialization.” (Siddique, 2023)

Fredrich Nietzsche said that “insanity in individuals is something rare – but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule.” Because Western culture has accepted traditional parenting as its established norm, it is unable to see how insane of a practice traditional parenting actually is, and by not challenging the status quo, a cycle of insanity is continually being perpetuated. In individualistic cultures, traditional parenting methods lack cognitive complexity due to Western egocentrism, which results in “I’m right and you’re wrong” hierarchies of authority. “Subject D” stated during their interview for this paper which can be found located in the field test results section regarding her experiences with conflict as a child that, “Children weren’t really considered people, so their needs and their wants and their personhood weren’t really considered equally…you can’t even really negotiate a conflict unless you acknowledge that the parties are equal.” Western egocentrism evolved into culturally accepted norms of punishment and reward systems, where children are taught to manage their behavior through expecting their adherence to strict rules with punitive consequences should they not do so. Traditional parenting methods expect children to obey and defer to their parents as a higher authority, and creates dialectical tensions between a child’s need for autonomy and their need for connection. When these needs for autonomy and connection are not met in childhood, these dialectical tensions become traumas, and attachment disorders occur. Traditional parenting tactics apply conditions to a parent’s love and approval, and when those conditions are not met, traditional parenting practices dictate punitive punishment, which include spanking, time-outs, having earned privileges revoked, or being yelled at, with the implicit goal of scaring a child into “being good.” These may change a child’s actions on the outside but will not change the internal issues that prompted the acting-out behavior. This traditional model for parenting has been our established norm for parenting our children for the past 200 years, ever since the Industrial Revolution, and it can breed anger, mistrust, rebellion and problems with authority well into adulthood. “If a child stops crying after someone ignores them, shames them, yells at them, or spanks them, they do not calm down; they shut down. For a developing brain, calming down is a relational process. It involves receiving empathy, understanding, and care,” said Eli Harwood, author of Securely Attached: Transform Your Attachment Patterns into Loving, Lasting Romantic Relationships ( A Guided Journal) (Harwood, 2023). Traditional parenting is now rapidly being replaced by “love based parenting” “attachment parenting” or “positive parenting” which for the purposes of this paper will be defined as “supportive parenting” that relies on mindful tactics such as connection, presence, helping children name what they are feeling, and developing corrective but supportive solutions. It’s okay to set rules, for example, but it’s important to ensure they know these rules ahead of time while being consistent and reasonable in how those rules are enforced. Effective disciplinary strategies set clear and appropriate expectations, and then caregivers work together with children to understand what is getting in their way if they find it difficult to meet those expectations. “Toddlers have only two action items on their agenda: play, and deep emotional connection with their parents. If you’re struggling with their behavior, their life is likely lacking in one of those two ways,” stated Robin Einzig, Founder of Visible Child (Enzig, 2022).

According to the Global Initiative to End all Corporal Punishment of Children, corporal punishment is defined as “any punishment in which force is issued and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.” Examples include shaking, kicking, forcing ingestion (soap, hot sauce), “smacking”, “slapping”, or “spanking”, and also include nonphysical forms of punishment such as verbal and emotional abuse, or activities intended to cause shame to a person, such as humiliation, threats, ridicule, etc. (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018) “Vast amounts of research have consistently demonstrated strong correlations between youth who experienced harsh punishment from their parents and increased risks of changes in brain physiology that show on MRI studies, mental health disorders, misconduct, aggressive behaviors, and adverse outcomes that extend into adulthood.” (Lang, page 156). This can include shrinking of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in particular. The prefrontal cortex is one of the last areas to mature in the brain, and is thought of as the place where the personality resides. It is where an individual takes in input from their external world, processes it, and uses that information to instantly react to their experiences without conscious thought. A study published in Neuroscience in 2018 identified two specific areas ( DLPFC and OFC) in the prefrontal cortex of the brain that are responsible for the executive functions related to inhibitory control, planning and problem solving, delay discounting, and risky decision making (areas that may affect how an individual’s morality is perceived by others, or how the judge themselves). This study showed how both DLPFC and OFC work interdependently to contribute to both cognitive control and emotional-motivational aspects as an integrated hot and cold network (Vahid, et. al., 2018, page 119) (Figures A and B).

Punitive discipline leverages shame as a teaching tool, which results in a child experiencing disruptions to their attachment bonds with their caregivers, damaging the brain’s development during a crucial period in an individual’s life, and that faulty wiring in the brain results in insecure dysfunctional relationships as an adult. “The right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is about maternal bonding. It functions as a primary regulator of the amygdala. Early maternal connection causes the OFC to grow in size in the first few months of life, overlapping the frontal tip of the left prefrontal cortex. The cortex has plasticity, so even through adversity and trauma, as a child grows, connection and attunement help to mitigate the activation of the amygdala. A poorly developed OFC is correlated with attachment disorders among other challenges creating negative plasticity – the physical malleability of the brain in stress,” said Robert Scaer, M.D. (Scaer, 2014). The right OFC is responsible for childhood bonding to caregivers, and it is also responsible for controlling and correcting reward and punishment related reinforcers, showing a clear connection between attachment and discipline in the structures of the brain itself. Even time outs, which were at one time considered to be a more humane alternative to spanking, are now known to cause significant emotional distress in children. “We are all social animals and have a deep need for connection. Human beings are wired for social interaction, and isolation can have a detrimental effect on our health and well being” (Sapolksy, 2018). Professor and author Brené Brown says that shame is the fear of disconnection, and safety is a sense of validation and belonging (Brown, 2007). When a parent leverages their child’s connection to them in order to force compliance, it creates a core abandonment wound, which results in problems trusting their caregivers, and this mistrust then manifests as maladaptive and dysfunctional means for achieving connections as an adult who will have difficulties individuating into a fully mature grownup (Madigan et. al., 2016) (Beaudoin and Bernier, 2013) (Tarrin-Sweeny, 2013) (Kerig and Beker, 2010) (Meuller et. al., 2013). The right OFC is also responsible for coordinating the retrieval of explicit memories for use in speech and thus a poorly developed OFC will result in communication difficulties. It is hypothesized that the right OFC plays a significant role in our decision making process as well, which indicates that poor attachment in childhood will lead to poor choices as an adult (Gore et. al., 2023). The methodology for this research paper describes a measurement that the researcher referred to as an MES index, which may potentially indicate a poorly developed OFC. Lower MES index scores (less difference between measured levels of morality and EQ) initially appear to correlate with lower levels of cognitive complexity (refer to proof of thesis below). A higher MES score may indicate greater cognitive complexity and a more matured OFC.

French sociologist Émile Durkeim (1858-1917) concluded that the moral constitution of a society is what determines its suicide rate. (Nehring, 2014, p.96-115) Durkeim believed that suicide rates were based on the imbalance of two social forces: social and moral integration. In a recent cohort study using twins, childhood adversity was linked to increased odds of psychiatric disorders (Daníelsdóttir, et. al., 2024). At the time of Durkeim’s writings, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) had yet to be discovered. When the morals in a society decline, the instances of ACEs increase, which in turn cause higher suicide rates. Morals can be defined as the standards that guide a person’s behavior and choices. They inform an individuals’ beliefs about what is or is not acceptable. Virtually everyone is familiar with the Golden Rule and the adage of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” which implores society to act considerately. However, this doesn’t work well when others would like to be treated differently than what the other may prefer. Milton Bennett proposed that to overcome issues of differing wants, a Platinum Rule of “do unto others as they themselves would have done unto them” helps individuals to understand how others think and what they want before acting. It implies that empathy is a prerequisite for moral sensitivity. (Adler and Proctor, 2017) Many other studies have been done that connect empathy to moral development (Narvaez, 2010) (Aquino and Reed, 2002) (Aquino et al., 2009)(Pathak et al., 2012) (Mestvirishvili et al., 2020), while other studies have looked at the impacts of shame on mental health (Yakeley, 2018) (El-Jamil, 2003) and on the impacts of shame and humiliation on moral decision making (Nelissen, 2013)(Silfver-Kuhalampi et al., 2015). Robert Sapolsky, who has researched extensively in the fields of neuroscience, psychology, and evolutionary biology for decades, said that “empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Empathy is essential for building strong relationships and creating a just and compassionate society” (Sapolsky, 2018). This research project connects an individual’s abilities to act on their morals with their abilities to regulate and control themselves and evaluates how the area of the brain responsible for cognitive complexity or the ability to perspective shift is related to areas of the brain damaged by punitive discipline. The field experiment results show that the development of adequate self control and emotional self regulation by which a person acquires the means to act on their morals is determined by the methods of discipline that were experienced in childhood.

The primary research paper used for the literature review portion of this paper was “Attachment as a Mediator between Childhood Maltreatment and Adult Symptomatology,” written by Robert T. Mueller, Kristin Thornback, and Ritu Bedi, published by the Journal of Family Violence (2012). This study looked at how attachment between caregiver and child could potentially mitigate the effects that childhood mistreatment and abuse have on the later development of adult mental disorders. By connecting their own work with multiple other studies already done on the topic, including one published by Trickett and McBride-Chang (1995), it links insecure attachments with caregivers in childhood to “increased levels of delinquency and criminality, difficulty controlling aggression, social withdrawal and difficulty in relationships,” and with being “more likely to interpret the actions of others as hostile.” The paper by Mueller, Thornback and Bedi cites multiple other sources who show that almost all of what is thought of as “mental illness” is actually trauma from childhood; the memories of which can be forgotten by adulthood but still shape subconscious behaviors. It relates psychological symptoms including what might be considered deviance in adulthood with the experience of insecure attachment as a child. They also emphasize the importance of viewing this as a systemic issue, not just an individual one. Their findings support the thesis proposed in this field study which looks at the effects of punitive discipline on human behavior. They created vital academic dialogue around the subject and the previous studies they cite indicate that secure attachment is crucial for an individual’s healthy psychological development. During their analysis of John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, the authors of this study stated that insecurities in attachment “represent an individual’s level of fear of abandonment in relationships,” (Meuller, et. al., 2012, page 244). This ties directly into this paper’s field research and subsequent analysis on the impact of abandonment wounds on the childhood development of the right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which is responsible for maternal bonding. The right OFC is also responsible for controlling and correcting reward related and punishment related reinforcers. In other words, it assists in establishing the Western cultural norms surrounding discipline practices. (Figure A) Therefore, a key focus point of this field research is connecting caregiver bonding in childhood and adult deviant behaviors with how society approaches discipline methods.

The Mueller, Thornback and Bedi study looked at the role of caregiver attachment in mediating childhood abuse, and how that affects the development of adulthood mental illness and psychological symptomatology. It specifically looked at how disruptions to attachment result in an individual externalizing and internalizing their emotions. The participants in Mueller’s study were undergraduate students whose data was gathered through use of a questionnaire. The researchers rated their participants’ attachment styles, emotional and behavioral problems, trauma histories, and experiences of abuse using a sequence of four separate questionnaires previously developed by other researchers. The researchers analyzed this data in order to correlate and determine the relationships between abuse, attachment, and psychological symptoms. Variables in attachment accounted for 85% of the variances in both attachment anxiety and avoidance. They used structural equation modeling to conclude that there is a direct link between childhood attachment and adult symptomatology (Meuller, et. al., 2012, page 248). Their study found that adult attachment in close relationships partially mediated the effects of psychological maltreatment on externalizing and internalizing [emotions], and trauma related symptomatology. (Meuller, et. al., 2012, page 249). This is a key point, and these study results indicate that experiencing safe and secure attachments in adulthood can help to mitigate the development of and lessen the impacts of mental illness among those impacted by insecure attachment, which parallels the results of my field research.

They state that “In a meta-analysis including 105 studies using the Adult Attachment Interview, van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg (2008) found that individuals with insecure attachment styles were over represented in clinical groups with both internalizing and externalizing disorders.” (Meuller, et. al., 2012, page 244) and also state that “a large scale meta-analysis performed by BakermansKranenburg and van IJzendoorn (2009) revealed that approximately 56% of individuals in non-clinical adult samples were classified as securely attached.” That means that slightly under half of all adults everywhere suffer from poorly developed and maladaptive coping strategies in their adult relationships. This data implies that insecure attachments are a massive hidden health crisis, one that this research project hopes to continue to shed more light on. The Mueller et. al. paper stated that “the negative effects of childhood maltreatment on the attachment system is important because of the impact it has on children’s functioning.” They go on to explain these impacts, which constitute the basis for this field research project. Their paper showed that insecurities created in childhood manifest as problems in later adult relationships, which all of the five subjects in this research paper have illustrated through their qualitative interviews collected here, confirming that punitive discipline methods result in adulthood difficulties with self control and emotional self regulation, which results in impulsive and aggressive behaviors.

This research takes an interpretivist approach by collecting qualitative data through five in depth interviews in order to analyze information regarding how individuals experienced conflict in their childhood. It then contrasted that with their experiences in adulthood and compared their childhood experiences with any current deviant behaviors, then analyzed the results through a lens of both DAT and Situational Control Theory (SAT) (Fiedler, 1978). SAT suggests that people may not behave morally when experiencing stress due to a temporary inability to exercise self control. SAT “proposes that the causes of human actions are situational. The theory further proposes that humans are fundamentally rule-guided actors and that their responses to motivators are essentially an outcome of the interaction between their moral propensities and the moral norms of the settings in which they take part.” (Wikström, 2014) SAT argues that when outside pressure is exerted on an individual, they may not act in accordance with their personal morals or values, because they fail to exercise self control. “Viewed in concert, it is fair to say that morality and self-control interlock and form what we call moral self-control whenever people need to suppress a selfish impulse or desire in the service of a less selfish (e.g., cooperative, prosocial) moral value or goal.” (Hofmann, Meindl, Mooijman, Graham, 2018) The results of this study show that adulthood difficulties in emotional regulation and self control can be correlated with experiencing a lack of supportive correction in childhood.

METHODOLOGY:

I chose to study the topic of generational trauma and the different types of communication associated with various attachment styles because I wanted to study how different methods of childhood discipline could potentially correlate with adult behavior patterns. This study is based on the research that I performed independently during my own trauma recovery following separation from a dysfunctional family system, and thus a personal bias was potentially introduced to the study in the initial topic choice. The research for this paper and study was gathered with this bias in mind and an effort was made to be objective and remain detached from the outcome and the process, and this was done by attempting to not influence my subjects’ answers in any way, even when prompting them to provide further clarifying information. It is believed that the data gathered from all five subjects of various ages and genders is an accurate representation of what the findings would be among similar individuals outside of this research project. I did confirm these numbers through the use of a separate informal observation of my Interpersonal Communications class, included in a footnote here.

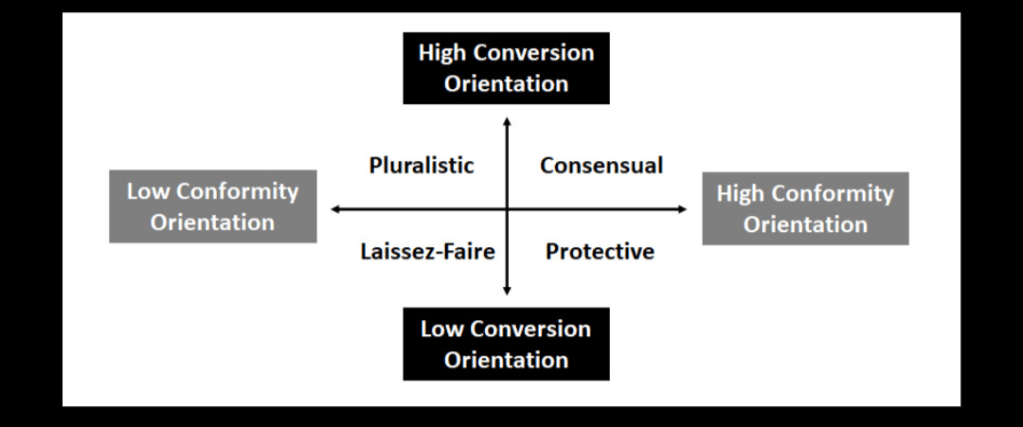

Family Communications Theory (Model A) was developed by Ascan F. Koerner and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick (2002). It views the family as a social system, and divides these family systems into categories of communication through four distinct patterns. The four family communication patterns are consensual (high conversation, high conformity), protective (low conversation, high conformity), pluralistic (high conversation, low conformity), and laissez-faire (low conversation, low conformity). Families with high levels of conformity produce children who have a fewer number of interpersonal skills in their adult relationships (Koesten, 2004), are conflict avoidant, and tend to be more hierarchical, with a clear sense that some members have more authority than others (Alder and Proctor, 2017). Families with low conversation orientations interact less and are more emotionally distant. Conflict tends to be avoided in these families, and they are characterized by power plays and refusal to have an open dialogue. In protective families (low conversation, high conformity), obedience to authority is emphasized. Protective family members typically scored low on communication skills (Samek and Reuter, 2012). Pluralistic families produce offspring that are less verbally aggressive than any other type (Schrodt and Carr, 2012). In pluralistic families, all family members’ contributions are valued and evaluated on their own merits. Studies have shown that in addition to the association between communication and family closeness (Schrodt, 2006; Vazsonyi, Hibbert & Snider, 2003) FCT communication patterns are also associated with the amount and quality of of intimacy shared in close adult relationships following childhood (Ledbetter, 2009). Pluralistic families tend to be more securely attached, and utilize supportive discipline methods. The other three types of patterns tend to result in more insecurely attached family members. Based on the results of the field experiment here, as well as in previous studies that show a direct link between low conformity and low aggression (Schrodt and Carr, 2012), pluralistic patterns are the optimal and ideal FCT category.

I used FCT categories while analyzing the data gathered from my five research subjects to categorize the FCT types experienced in childhood based on the interview results. Of the five subjects consenting to give interviews for this research project, Subjects A, C and D describe their families of origin as being Protective (low conversation, high conformity), Subject B describes his family as being Pluralistic (high conversation, low conformity), and Subject E described her family as being Consensual (high conversation, high conformity). Given a reasonable margin of error, these numbers appear to correlate to the numbers acquired with my observational class poll referenced in the footnote.

This study analyzes the qualitative data obtained through interviews by using Differential Association Theory (DAT), which was initially proposed by Edwin Sutherland in 1939 (Sutherland, 1995) and revised in 1947. DAT proposes that people learn deviant behavior through their interactions with others. This paper assumes that behavior is learned from others through the processes of behavioral modeling and positive or negative reinforcement as well as through communication, and that most of this learning happens within our intimate personal groups and relationships, specifically through Family Communications Pattern Theory (FCRT) (Compton and Craig, 2019) (Hesse, et. al., 2017). This paper also looks at the data through a lens of Control Theory, which proposes that weak bonds between individuals, such as seen with attachment disorders, are responsible for creating opportunities for individuals to deviate from the expected norms for their behavior.

Two ethical issues in qualitative research include confidentiality and the role of the researcher as a data collection instrument. The identities of the research subjects in this study have been disguised to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants. The subject matter is sensitive and was potentially emotionally upsetting to participants, but every effort was made during the interviews to avoid harming the research subjects. They were made aware of the topic and nature of the research prior to obtaining their consent to participate in the study.

During the data collection process, the interviews were recorded and these recordings were directly transcribed before any analysis took place. A series of six questions were developed for qualitative interviews, which included two questions intended to inquire into the subject’s experiences with discipline and conflict in their childhoods. Two questions were asked about their current conflict resolution skills and self regulation abilities, and two questions which required them to define morality and ethics by giving personal examples. Test subjects A, B, and C were asked these six questions initially, then they were followed up with regarding a final seventh question that was developed a month later, which asked them specifically about impulsive and aggressive behaviors. This final question was based on the study “Parent Grandiose Narcissism and Child Socio-Emotional Well Being: The Role of Parenting,” first published online October 19, 2023 (Rawn, Keller, Widiger, 2023). Since Rawn et. al.’s study was directly related to the topic of this study, the added question was shown to be a necessary step, and the timing of the last question was not deemed problematic to the results of this study. “In terms of takeaways from the paper – for parents, it would be the knowledge of what parenting practices to use,” Rawn told PsyPost (Dolan, 2023). “Specifically, those that are more positive (e.g., emotional warmth, autonomy support, and use of democratic discipline) rather than those that are more negative (e.g., punitive or permissive discipline).” Subjects D and E were contacted after this revision was made, and were asked all seven questions at the same time. Following their completion and transcription, the interviews were analyzed for communication, relational and behavior patterns repeating over time.

A conscious attempt was made to get a wide range of ages and genders for demographic sampling. Subjects A and B are both people that I met online and have a casual acquaintance with. Subject C is my caregiver. Subject D is a friend of mine, and Subject E is a classmate. None of the participants received any financial compensation or incentives in order to participate in this study. It is important to note that they may have been more willing to share deeply personal details because of an existing relationship with me prior to this study. In order to minimize harm done to my subjects due to the sensitive topics discussed in our interviews, I attempted to remain both nonjudgmental and empathetic while gathering my data. Because this research relies solely on oral reports, the participants’ own personal bias may have been unintentionally introduced, and therefore it is recommended to perform further in depth longitudinal research in this area in order to more fully understand the dynamics of socio-emotional development and the impact that both parenting styles and the communication styles experienced in child have on adult mental health. Before the interview, the participants were asked to complete two online quizzes that measured their levels of emotional intelligence and morality. Given the relatively small sample size, a larger study could be justified through the results that were obtained here.

FIELD EXPERIMENT:

Subject A

Age: 45 years old

Gender: Questioning

Location: Washington state

Diagnosis: Bipolar (BPD) and PTSD

Overall EQ result: 66.19% (high)

Morality quiz results: 72% Nurture

MES score: 5.81

Subject A was informed of this study and asked to participate via text message. They are an online acquaintance of mine, and have no direct relation to me. After consent to participate was obtained, they were sent two links to two online surveys via text and asked to screenshot and send me back their results.

After the results were obtained from both quizzes, a time was arranged to have an interview over zoom video call, where Subject A was asked six questions about their experiences in childhood and their current life experiences in adulthood. Subject A interviewed on Saturday, October 28, 2023 at 6:00 pm Pacific Standard Time. I sent them a link with my zoom meeting information. They were told that their name would be kept confidential to protect their anonymity and that their personal details may be used for data collection and analysis purposes. They were informed of the purposes of the study and asked to provide their verbal consent over video, which they did. They agreed to sign a consent form, which they did. I identified my study as being performed under the guidelines of the American Sociological Association’s code of ethics and a copy of this was offered to them. They were provided with a copy of the original research plan and indicated they understood the purpose of the study and their role in it. The following interview took about 20 minutes to complete, and was recorded for later transcribing.

The interview questions each subject is asked in this study are as follows:

When you were a child…

What methods of discipline were used?

How was conflict handled in your home?

As an adult…

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one?

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

How do you personally define morality?

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

When you were a child, what methods of discipline were used?

“My parents used spanking roughly until my sister was born, I don’t actually remember being spanked but I know that I was. My dad is now and has been for most of my life a pretty dedicated pacifist, he was opposed to it but he had let my mom decide at first. But then he changed his mind about that when my sister came along. So, a little bit of spanking early on, after that, time outs and removal of privileges, you know, grounding and that kind of thing.”

How was conflict handled in your home?

“Pretty often, conflict was avoided. You know, it would just get kind of avoided and not really talked about. And then when it actually, like, came up, it would be kind of explosive, like, screaming at each other and that sort of thing, which didn’t happen often, but happened more often with my mom than with my dad. But with my dad it would get much more explosive, but that would only happen like once every few years.”

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one now?

“I try to bring it to them, I’m not always perfect about it but I’ll try to bring it to them and let them know preferably before I get too worked up about it so that I can remain calm about it. And I have been working on and have been relatively successful at avoiding escalation so that if they’re resistant to resolving the conflict and it doesn’t seem like it’s going anywhere, I’m able to back off and not push, but that’s been more of a recent development, basically over the past year since going to jail.”

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

“I will generally escape into video games, smoke weed and kinda space out, stare at my phone. Until I can get into a place where they are manageable enough that I feel like they’re not going to control my actions. And then if there’s anything I can do about the root cause of them, then I’ll try to. Sometimes I can’t, sometimes I just have to endure; in that case I’m just going to have to endure; in that case I’m just going to dissociate more.”

How do you personally define morality?

“Morality is what you consider to be right and wrong. It’s where you’re going to point at something and go “No, that’s not okay” (emphasis theirs). Morality is what you’re okay with.”

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

“I think that the most recent and the most dramatic of those would be reconciling with [Subject A’s wife, her name is redacted]. And I was faced with this choice of, am I willing to do what it takes to repair things with somebody who has wounded me really deeply. It’s not going to be easy and I knew that it wasn’t going to be. I knew that whatever it took and whatever I had been through, it was still worth it. I was able to just kinda get into my own feeling of that and I could see that, yeah, there was going to be work. There was going to be suffering and it was worth it.”

On November 20, 2023 at 4:55 Pacific Standard Time, Subject A was contacted over zoom and asked one follow up question regarding impulsive and aggressive behavior. The interview lasted approximately 6 minutes. For added context, Subject A and their wife practice polyamory, and their response indicates that.

As an adult…

Have you ever struggled with impulsive or aggressive behavior, or had difficulties in self control or emotional regulation? Can you give one example of that?

Their response was as follows:

“That is absolutely something that I’ve struggled with frequently. The clearest example would be relatively recently. Getting in a fight with [wife’s name omitted]. It started out with, there was a new guy that was she was talking to, we’d had some friction because I had been wanting to meet her other partners, her other potential partners, and she hadn’t really wanted me to meet them, and so then this one, she was like, okay, you can meet him, he can come to our place. And I was like, I’d like to meet him before he comes to our place. And there was conflict about that, we were arguing about it in the car. We get home and I’m not doing well, I’m just kind of like shut down, and not wanting to be around her. Let’s see, trying to remember. I’ve told this story a lot of times but it’s been awhile so I don’t remember anything because it’s a kind of trauma fog. Let’s see, I shut down for a while, and we ended up going to bed, and then the next day, like, along the way there was a knife involved. I put the knife where I could get it because I was scared of her, I don’t remember exactly why that was, that I was scared of her, but I remember that. So then I’m shut down for awhile, it’s like a day that I’m shut down and just not doing well. Next day, I’m telling her to stay back and give me space. She won’t. We’ve got just one bed in the trailer so I’m like no, you need to sleep in the other space, over in the yurt, which is not maybe the best bed but I’ve slept there to give her space before. Like, you need to go there and give me space. So I’m telling her that she needs to leave because I am crazy enough that I don’t feel like she’s safe. And then I push her out of the bed and she comes back with a knife, not the same knife mind you, a knife from the kitchen that she has stashed under the bed. She comes for me with it, we wrestled for a bit, I get her held down until she puts that down, and finally leaves and goes and sleep in the other space. Next day, my dad comes to visit, and that goes reasonably well. During the altercation, she’s messed up my glasses a bit, they’re not completely broken, I can still kind of slightly wear them, but they’re not working very well. I tell her that I found a place to get them fixed and she’s like well, I’m not paying for that, we can’t afford that, so it’s not happening. Um, I go for her and try to go for her glasses, that turns into another fight, and that ends up with the police being called and me going to jail. I’m kind of happy that I don’t have all the details printed in my mind any longer (laughs).”

Subject B

Age: 26 years old

Gender: Male

Location: New Mexico state

Diagnosis: Autistic Spectrum disorder, moderate to severe

Overall EQ result: 58.81% (average)

Morality quiz results: 100% Nurture

MES score: 41.19

Subject B was informed of the study and asked to participate via text message. He was an online friend of mine, and has no direct relation to me. After consent to participate was obtained, he was sent two links to two online surveys via text and asked to screenshot and send back his results.

After the results were obtained from both quizzes, a time was arranged to have an interview over zoom video call, where Subject B was asked six questions about his experiences in childhood and his current life experiences in adulthood. Subject B interviewed on Sunday, October 29, 2023 at 2:00 pm Pacific Standard Time. I sent him a link with her zoom meeting information. He was told that his name would be kept confidential to protect his anonymity and that his personal details may be used for data collection and analysis purposes. He was informed of the purposes of the study and asked to provide his verbal consent over video, which he did. He agreed to sign a consent form, which he also did. I identified my study as being performed under the guidelines of the American Sociological Association’s code of ethics and a copy of this was offered to him. He was provided with a copy of the original research plan and indicated he understood the purpose of the study and his role in it. The following interview took about 40 minutes to complete, and was recorded for later transcribing.

The interview questions asked in this study are as follows:

When you were a child…

What methods of discipline were used?

How was conflict handled in your home?

As an adult…

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one?

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

How do you personally define morality?

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

When you were a child, what methods of discipline were used?

“Usually, my parents didn’t really believe in the whole, like, corporal punishment thing, but if worse came to worse, I usually got either a time out chair when I was younger, and then as I got older, I would have things taken away, like as punishment. Like the computer, for example. When I was around 8 or 9, I think I started spending an ungodly amount of time on it.”

How was conflict handled in your home?

“Conflict would always be handled by my talking out the problem. The way that I observe it in my family, usually an argument would be brought up over something like finances, bills, who’s going to work and who’s staying to watch the kid.The problem would be addressed; I’d bring up my side, they’d bring up their side.”

Subject B then indicated at the researcher’s prompting that he had felt safe disagreeing with his parents, and that conflict in childhood had not inspired a fear response in him. He had the general feeling that his needs would be met, even if he didn’t get what he wanted.

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

“I distract myself. In whatever form that may take, it may be either, like, part of it would be like workaholism but also just doomscrolling. I think in the past I would spend up until 2 or 3 in the morning just scrolling Facebook. And I’m trying to get better about that because there are times when you really need to wake up earlier. I think it also ties into another one of my bad habits, procrastination. Last minute crams, days and days of putting it off until finally I have to do this eight hour cram session.”

How do you personally define morality?

“Morality, I think, is doing what you feel is right for the betterment of everyone, even at great personal sacrifice. Like even if it turns out you stand to lose a lot from it.”

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

“Summer 2020, was of course the wave of Black Lives Matter protests, there was a whole lot of police brutality killings that had been happening since, but the three big ones were: Ahmad Avery, who was killed by neighborhood vigilantes; George Floyd who killed by a cop who knelt on his neck for nine minutes; the Breonna Taylor incident where these cops barged into Taylor’s apartment apparently looking for somebody else, her partner at the time, and shot and killed her in a no knock warrant. There was a friend of mine who was a fellow music producer, and he basically shared a post on his story that kind of rubbed me the wrong way, because he was talking about Black Lives Matter protestors allegedly rioting even though a majority of the protests were actually peaceful, but also that there was the one way to be civilly disobedient, I as a white man have no moral high ground over which way to riot because in the 60’s, civil rights demonstrators did do nonviolent protests, and they had police dogs and fire hoses spraying on them and let on them. More or less, the situation with the friend was that he was basically posting things about Black Lives Matter protestors rioting, and I think I was kind of a little mad at him, he was producing stuff that was sort of in the vein of experimental hip hop and I basically wrote a call out post on instagram about it. Then another friend who I also knew since high school said that there was a lot of emotional distress that I may have caused him because of that post, and said that I should probably take it down. This is the day after, and I realized that maybe I should and I took it down. It kind of made me realize looking back just how much my conflict resolution skills, I need to work on those a bit. Or just not be afraid to have the hard conversations.”

On November 9, 2023 at 5:00 pm Pacific Standard Time Subject B was contacted again by the researcher over zoom to be asked one question, which the researcher had forgotten to ask him during his initial interview. This interview lasted approximately two minutes.

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one now?

“I think the first thing I try to do is talk to them about the problem, when I can, like just articulate what I feel about it, that’s if I’m comfortable going up and telling you about it. But then there’s another side of me that’s like, you know, non confrontational, so sometimes I’ll delete a post [on social media].”

On November 19, 2023 at approximately 4:20 pm Pacific Standard Time, Subject B was contacted over zoom and asked one follow up question regarding impulsive and aggressive behavior. This interview lasted 3 minutes.

As an adult…

Have you ever struggled with impulsive or aggressive behavior, or had difficulties in self control or emotional regulation? Can you give one example of that?

His response was as follows:

“One thing where I’ve been really impulsive is impulse buying. It’ll usually be like an item of clothing or like a pair of shoes or jeans. I think a thing with one of my older jobs in laser tag, sometimes I would have to raise my voice because, you know, trying to get all these kids in line, sometimes I would…not like at them, I don’t raise my voice at them, it’s just like, “alright everyone; line up.” It’s not like I’m anger prone. I think my issue is more that I bottle it up.”

Subject C

Age: 53

Gender: Female

Location: Washington state

Diagnosis: none

Overall EQ result: 88.57% (very high)

Morality quiz results: 96% Nurture

MES score: 7.43

Subject C was approached in person, informed of the study and asked to participate directly. She was formerly employed as my caregiver, and has no direct relation to me. I acknowledge that there may be potential power dynamic issues due to being Subject C’s former employer, however, there was no additional financial compensation offered to Subject C for their optional participation in this study, and her answers did not appear to be influenced in any way by our relationship. I chose her due to my bias that having a study participant in a career field such as caregiving, which requires high empathy and nurturing skills, could potentially provide valuable data regarding how childhood experiences could affect later career choices. After consent to participate was obtained, she was sent two links to two online surveys via text and asked to screenshot and send back her results.

After the results were obtained from both quizzes, an interview was conducted in person at my residence, where Subject C was asked six questions about her experiences in childhood and her current life experiences in adulthood. Subject C interviewed on Thursday, November 9, 2023 at 3:20 pm Pacific Standard Time. Her interview was recorded on my laptop for later transcribing. She was told that her name would be kept confidential to protect her anonymity and her personal details may be used for data collection and analysis purposes. She was informed of the purposes of the study and was asked to provide her verbal consent over video, which she did. She agreed to sign a consent form, which she did as well. I identified my study as being performed under the guidelines of the American Sociological Association’s code of ethics and a copy of this was offered to her. She was provided with a copy of the original research plan and indicated she understood the purpose of the study and her role in it. The following interview took about 5 minutes to complete, and was recorded for later transcribing.

The interview questions asked in this study are as follows:

When you were a child…

What methods of discipline were used?

How was conflict handled in your home?

As an adult…

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one?

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

How do you personally define morality?

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

When you were a child, what methods of discipline were used?

“Let’s see, grounding, and I got beat with a switch from a tree. (Subject C then laughed) For really bad stuff.”

How was conflict handled in your home?

“Usually we just hashed it out, like we talked about it. Or fought. It depended on who it was with. But my mom, we never sassed back to our mom. So it was usually just us kids fighting.

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one now?

“I usually just tell them that I don’t agree with you. And we talk about it. Calmly.”

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

“I usually talk to a friend about them.”

How do you personally define morality?

“I think morality is doing the decent thing, doing the right thing when no one’s looking. That knowing in your heart that it’s the right thing. And when you feel like doing something bad, don’t do it.”

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

“Usually in my heart I know what the right decision is, but it’s always your heart and your mind doing battle, so usually I just think really hard on it, thinking, what’s the best thing for me? And then of course I talk to my friends and family about it, depending on what it was. So I would talk to them about it and see what they thought, get their opinion, what they think I should do, and then consider what they said and then basically make the ultimate decision myself.”

On November 20, 2023 at approximately Pacific Standard Time, Subject C was asked one follow up question in person regarding impulsive and aggressive behavior. This interview lasted approximately 6 minutes.

As an adult…

Have you ever struggled with impulsive or aggressive behavior, or had difficulties in self control or emotional regulation? Can you give one example of that?

Her response was as follows:

“Yes, my whole life. One time my boyfriend was being mean to me, and I was sticking up for myself. And it was really frustrating. And then I was yelling and screaming, and then I smacked him. (laughs) That was a big fight. One time I whipped out my 9 millimeter. Another time I grabbed a hanger and he was like, “Oh, you want to hit me with that? Go ahead, hit me with that!” So I picked it up and started whaling at him, broke the hanger, and he was laying on the ground going, “Ow! Ow! I didn’t know you were that strong!” And I go, well now you do. Makes me laugh now. Actually, I laughed then.He literally crawled out of the bedroom, and he was drunk, like wasted, and he slunk back in like ten or fifteen minutes later and crawled into bed like quietly so I wouldn’t wake up. That was another, he was harassing me and wouldn’t let me go to sleep and like, he knew I had to get up super early for work and I had had a long day. He just wouldn’t leave me alone, he just had to keep arguing over some bullshit that he made up in his head. And I’m like I don’t want to argue, you’re imagining shit, I just don’t want to deal with this right now.And he just kept coming in and out to wake me up, coming in and out. “Get the fuck up, get the fuck up!” I’m like, leave me alone. I need to go to work tomorrow, just leave me alone. “Get out right now!” It was bad. And it just sucked. It’s like, I think about it, like, why did I live like that, for even a second. I felt like I had no one to turn to. Then they suck you back in with their promises and they’re super nice for like a month or however long. Then it’s right back to the same old shit.I know women are like that too, but I feel like men are worse. Like there’s more men like that than women. Something is wrong with their psyche, or the way they were raised.”

Subject D

Age: 40 years old

Gender: Female

Location: Washington state

Diagnosis: Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder, suspected Autism Spectrum Disorder

Overall EQ result: 60.47% (high)

Morality quiz results: 81% Nurture

MES score: 20.53

Subject D was informed of the study and asked to participate via text message. She is a personal friend to me, but has no direct relation to me. After consent to participate was obtained, she was sent two links to two online surveys via text and asked to screenshot and send back her results.

After the results were obtained from both quizzes, a time was arranged to have an interview over zoom video call, where Subject D was asked seven questions about her experiences in childhood and her current life experiences in adulthood. Subject D interviewed on Sunday, November 19, 2023 at 5:15 pm Pacific Standard Time. I sent her a link with the zoom meeting information. She was told that her name would be kept confidential to protect her anonymity and that her personal details may be used for data collection and analysis purposes. She was informed of the purposes of the study and asked to provide her verbal consent over video, which she did. She agreed to sign a consent form, which she also did. I identified my study as being performed under the guidelines of the American Sociological Association’s code of ethics and a copy of this was offered to her. She indicated that she understood the purpose of the study and her role in it. The following interview took about 20 minutes to complete, and was recorded for later transcribing.

The interview questions asked in this study are as follows:

When you were a child…

What methods of discipline were used?

How was conflict handled in your home?

As an adult…

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one?

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

How do you personally define morality?

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

Have you ever struggled with impulsive or aggressive behavior, or had difficulties in self control or emotional regulation? Can you give one example of that?

When you were a child, what methods of discipline were used?

“Mostly like, loss of privileges, or like having to go to your room. Yeah. I think those were the main ones.”

How was conflict handled in your home?

“Oh, um, it wasn’t. (laughs) You might have guessed that. Conflict…I don’t even know how to talk about how conflict was handled in my home, because it wasn’t. Children weren’t like, people people, so like, their needs and their wants and their personhood weren’t really considered equally so, like, you can’t even really negotiate a conflict unless you acknowledge that the parties are equal. So we were just kind of, me and my brother, we were just expected to not cause problems and do as we were told and kind of suck it up, so there really wasn’t any conflict, like we just had to deal with whatever, I guess. Sometimes yelling, sometimes the silent treatment, but never anything constructive (laughs).”

What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one now?

“When I was younger I would have said that I was just extremely conflict avoidant and I would maybe even change my behavior to avoid the conflict, now I’m more likely to bring it up with someone if I’m having a conflict. But that’s not necessarily true because actually I’m kind of having a conflict right now and I’m not addressing it (laughs), with a friend and I don’t know what’s going on with her lately, but she basically said, paraphrase, “stop talking about being Autistic around me.” Because it triggers her, but she can’t be specific about what’s triggering, and what I get is that my identity is triggering, and so lately I’ve just been totally avoiding the entire topic. And then quietly like, researching autism on my own. (laughs) So yeah, I definitely do still avoid subjects that are likely to cause conflict with people. That one blindsided me though because I didn’t expect an assertion of my identity to cause a problem for somebody else. But I guess it does. But in my, what do you call it, in my partnership, I’m more likely to bring up something that bothers me with my partner than I have been in the past, because they’re more responsive to it. So what would I do? I’m pretty able to verbalize what’s bothering me. I don’t know what else there would be to do in resolving a conflict. It depends on the relationship, maybe. I try not to be resentful and escalate the conflict and I’ve never really done that, but I guess that’s another option. I guess if I’m not actively avoiding it then I would bring it up to them verbally.”

How do you cope with difficult feelings?

“Uh, eating. (laughs) I mean, unironically. I think we’re all having a lot of difficult feelings lately, and I noticed that food is a big coping mechanism for me. Healthy coping…how do I cope with my feelings…oh, you know, I do that Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired thing and see if there’s something physical I can address that will help and it usually does. Not so big on physical exercise, even though I’m aware that that would probably help. Try to get some UV exposure, maybe. Go outside and look at some scenery, I’m aware that that’s supposed to help.”

How do you personally define morality?

“That’s not something I spend a lot of time thinking about, so those inventories were really interesting. I haven’t really explored morality because I’m not sure it really exists. I think I have one, but I haven’t examined it much. My basic morality is not harming other people. You can’t dictate to others what they should and shouldn’t do. Although I found those three domains of morality interesting, like giving people liberty and stuff, because clearly I don’t think people should have absolute liberty to do whatever. So there’s something governing my morality but I’m not really sure what it is. I can’t point to anything when I was a child or anything. Maybe Mr. Rogers Neighborhood. (laughs) What was the other thing? The way that I came out Temperamental, and I’m like, yeah, well, I have my reasons (laughs) for being temperamental. And it doesn’t mean that I can’t mitigate it at all. Like I’m obviously not having meltdowns in public all the time, but yeah, I’m fairly emotional/temperamental.”

Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

“You know what’s funny? I don’t think I identify a choice until a situation becomes untenable, and then the choice is obvious. (laughs) I was thinking about my first marriage, I had exhausted the stay option. Like I tried that and I exhausted it, so there was only one choice left. I don’t do a pros and cons list or anything. Like, if the other person’s behavior stops and they’re willing to try, then I will pursue the stay option, but then if that’s not possible then it’s go. I pursue the less painful option until it’s no longer the less painful one.”

Have you ever struggled with impulsive or aggressive behavior, or had difficulties in self control or emotional regulation? Can you give one example of that?

“Pretty clearly I have. (laughs) It takes me a long time to get to that point but once all my resources are exhausted and I’m melting down I guess I can behave impulsively? I was watching a TikTok or something and this autistic person was talking about how they were in meltdown mode or whatever, and when they’re in meltdown mode they’re likely to throw stuff. And I’m like, oh shit, when I meltdown I throw stuff. So that’s an example. And I remember one incident when I was a teenager and I was stressed out, my parents were less than understanding, and we were having an argument or something and I just reached the end of my rope and there was a japanese garden trowel or something sitting around, and I just chucked it through the screen door. I’m not sure if the sliding glass had been shut I would have chucked it, but as it was it just went through the screen. Then my mom framed that as me being destructive, I guess, but it wasn’t even that, it was just impulsivity, because I had nothing left. One time I chucked a can of raisins, and this was like recent, like this summer. I had a little episode where boundaries got crossed in my relationship and I was very unhappy, and in the course of that I ended up chucking a can of raisins against the cabinet or something and they just went all over the place, like I was picking up raisins for, like, weeks, just finding them places, the raisins were pretty comical. I will try to grab something that’s not going to hurt anybody, but there have been times where it was glass or sharp, so. I never chucked it at anybody but I will chuck it at the wall and whatever’s on the wall. So yeah, I would say that I have an impulsivity problem. But I don’t have impulsivity problems like with ADHD where I like, spend all my money or, I don’t know, or move in with someone I don’t know very well, like I don’t have impulsivity like that. Because I avoid change, so that kind of impulsivity, no. But I think throwing stuff definitely qualifies.”

Subject E

Age: 20 years old

Gender: Female

Location: Washington state

Diagnosis: Depression, Anxiety, and ADHD

Overall EQ result: 54.29% (average)

Morality quiz results: 74% Nurture

MES score: 19.71

Subject E was informed of the study in class and asked to participate in person. She was my classmate, and has no direct relation to me. After consent to participate was obtained, she was sent two links to two online surveys via text and asked to screenshot and send back her results.

After the results were obtained from both quizzes, a time was arranged to have an interview over zoom video call, where Subject E was asked seven questions about her experiences in childhood and her current life experiences in adulthood. Subject E interviewed on Monday, November 20, 2023 at 10:00 am Pacific Standard Time. I sent her a link with the zoom meeting information. She was told that her name would be kept confidential to protect her anonymity and that her personal details could be used for data collection and analysis purposes. She was informed of the purposes of the study and asked to provide her verbal consent over video, which she did. She agreed to sign a consent form, which she did. I identified my study as being performed under the guidelines of the American Sociological Association’s code of ethics and a copy of this was offered to her. She indicated that she understood the purpose of the study and her role in it. The following interview took about 12 minutes to complete, and was recorded for later transcribing.

The interview questions asked in this study are as follows:

When you were a child…

- What methods of discipline were used?

- How was conflict handled in your home?

As an adult…

- What do you do when you disagree with a friend or loved one?

- How do you cope with difficult feelings?

- How do you personally define morality?

- Recall one instance when you were faced with making a difficult choice in life. How did you decide what to do?

- Have you ever struggled with impulsive or aggressive behavior, or had difficulties in self control or emotional regulation? Can you give one example of that?

When you were a child, what methods of discipline were used?

“My books were taken away on a few occasions, sometimes I was made to sit in the corner. I was only spanked maybe, four or five times at most over the course of my life, so that wasn’t really a big thing. Usually it was things taken away. First I would get my books taken away, and then I would get my kindle taken away when I was older, that sort of thing.”

How was conflict handled in your home?