The Self as a Mirror of Society

The traditional understanding of psychology and social theory treats personal dysfunction and societal dysfunction as separate domains. Individuals are expected to heal in isolation, while social structures are reformed through external policy changes. However, this division overlooks a fundamental truth: the individual and the collective exist in a reciprocal, reflective relationship.

Mirror Integration Theory (MIT) proposes that personal and societal dysfunction are not separate but mirror images of each other. Just as internal fragmentation within a person leads to psychological distress, systemic fragmentation in society leads to collective instability. Healing—whether at the individual or societal level—requires an integration process that reconciles these fragmented parts into a functional whole.

By synthesizing psychoanalysis, systems theory, trauma research, and addiction studies, MIT offers a holistic framework for healing individuals and transforming societies simultaneously. This theory challenges conventional approaches that treat personal healing as separate from social change and instead argues that the path to individual well-being is intertwined with the path to collective restoration.

I. Core Principles of Mirror Integration Theory

1. The Self and Society Are Mutual Mirrors

Just as a dysregulated nervous system leads to personal distress, a dysregulated society leads to systemic dysfunction.

Hierarchical control structures in society mirror internal psychological defense mechanisms.

2. Fragmentation is the Root of Dysfunction

Personal fragmentation (dissociation, trauma responses, unresolved parts) creates internal dissonance.

Social fragmentation (political polarization, systemic oppression, economic inequality) creates external conflict.

3. Healing Occurs Through Integration, Not Suppression

Traditional methods often attempt to suppress symptoms rather than integrate root causes.

True healing—both personal and societal—requires compassionate reintegration of rejected parts.

4. Addiction as a Collective and Individual Phenomenon

Addiction is not just a personal affliction but a reflection of society’s dysregulated coping mechanisms.

Societies with extractive economies and coercive institutions mirror addictive cycles of control, avoidance, and short-term relief.

5. Trauma-Informed Systems Lead to Sustainable Stability

Just as trauma-informed therapy promotes nervous system regulation, trauma-informed governance promotes social stability.

Punitive justice, coercive politics, and scarcity-based economies perpetuate societal dysregulation, mirroring how unresolved trauma perpetuates individual distress.

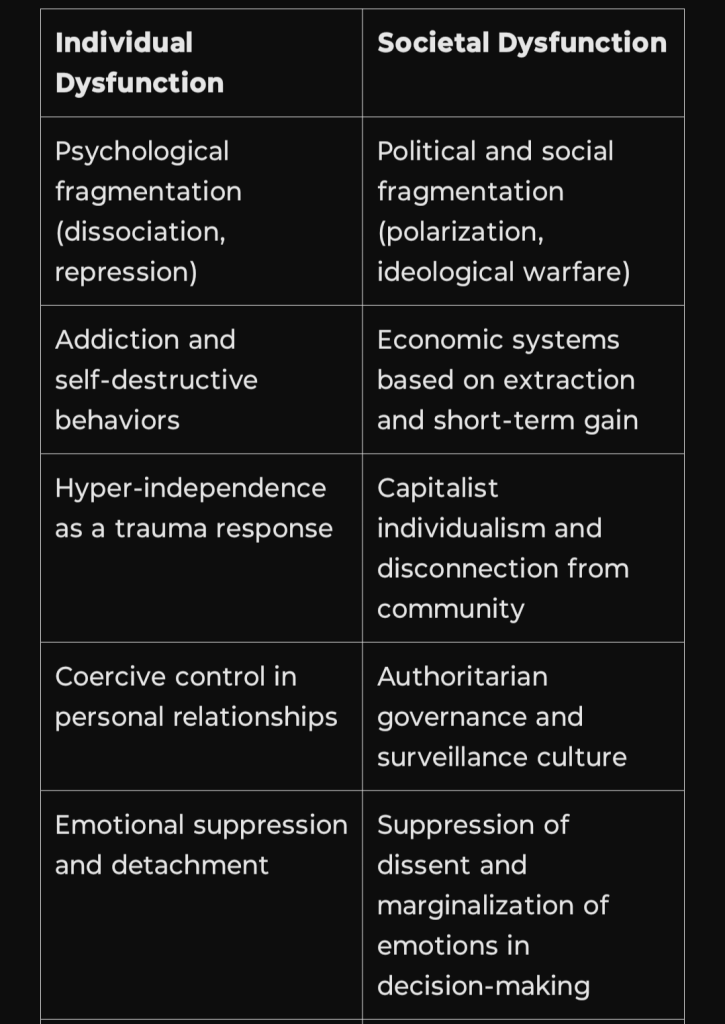

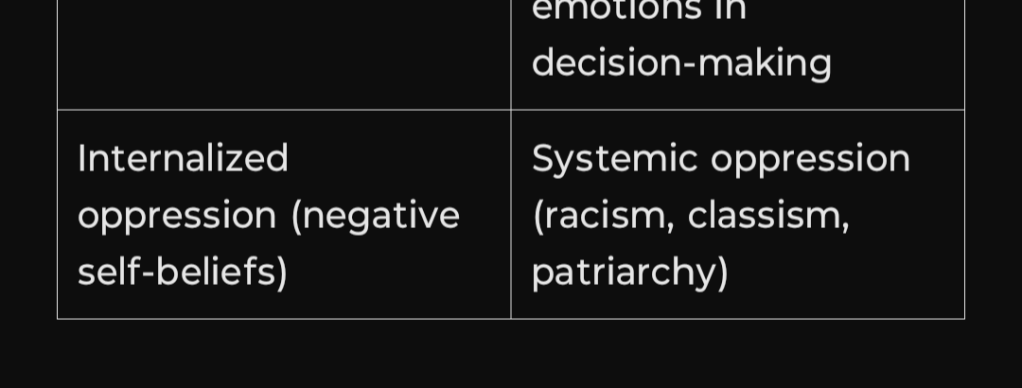

II. The Self-Society Mirror: How Dysfunction Manifests at Both Levels

MIT maps personal and societal dysfunction across four interconnected domains:

Just as an individual who suppresses emotions develops defensive mechanisms to avoid pain, societies that suppress dissent create oppressive institutions to maintain order. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of dysfunction, where personal and systemic wounds mirror each other and perpetuate suffering.

The key to breaking this cycle is integration rather than repression—both within individuals and within society.

III. Applying MIT to Healing: The Integration Process

1. Individual Healing: Internal Integration

Personal healing through MIT follows a self-integration process similar to Internal Family Systems (IFS):

Recognizing and befriending rejected parts (e.g., inner child, inner critic, protective mechanisms).

Moving from self-judgment to self-compassion.

Using co-regulation and relational healing to restore nervous system balance.

Rather than suppressing pain, MIT encourages individuals to acknowledge and integrate all aspects of the self—even the ones that society has labeled as “undesirable” or “broken.”

2. Societal Healing: Systemic Integration

Just as personal healing requires integrating rejected aspects of the self, societal healing requires integrating marginalized communities, suppressed voices, and neglected histories. MIT offers a macro-level integration process that involves:

Decentralizing power structures to prevent top-down coercion.

Shifting from punitive to restorative justice models.

Moving from extractive to regenerative economies (e.g., cooperative models, universal basic security).

Replacing hierarchical governance with participatory democracy.

Societies that embrace integration rather than suppression will move toward true social cohesion, rather than coerced stability.

IV. Addiction as a Societal Mirror: How MIT Explains Collective Addiction

A major component of MIT is its reinterpretation of addiction as both a personal and societal phenomenon.

1. Personal Addiction → Rooted in dysregulated nervous systems seeking temporary relief from unresolved pain.

2. Societal Addiction → Rooted in dysregulated economies and governance structures that rely on short-term fixes to maintain stability.

Examples of Societal-Level Addictions include:

The constant pursuit of economic growth despite ecological destruction.

The criminal justice system’s reliance on mass incarceration instead of rehabilitation.

The culture of workaholism that sacrifices well-being for productivity.

The military-industrial complex, which perpetuates cycles of conflict for economic gain.

Both personal and societal addictions function as avoidance mechanisms—they prevent deeper engagement with underlying wounds. The cure, according to MIT, is not stricter control or more repression, but integration and long-term healing.

V. The Future of MIT: How This Framework Can Be Applied to Social Change

MIT is not just a theoretical model—it is a practical framework for systemic transformation.

1. Trauma-Informed Governance

Policies should be designed around nervous system regulation.

Coercive institutions should be replaced with participatory, community-led models.

Governments should integrate relational trust rather than punitive control.

2. Economic and Financial Integration

Universal Basic Security (UBS) should replace scarcity-based economic models.

Worker cooperatives should replace exploitative corporate hierarchies.

Local economies should be designed for regeneration, not extraction.

3. Education and Knowledge Production

Curiosity-driven knowledge models should replace adversarial, debate-based systems.

Educational institutions should prioritize nervous system regulation and relational learning.

Decolonization of academia should elevate suppressed knowledge systems.

By implementing these changes, MIT can serve as a blueprint for both personal and collective integration—offering a path toward sustainable healing, non-coercive stability, and long-term social cohesion.

VI. Conclusion: A World Where Healing and Systemic Change Mirror Each Other

In a fragmented world, Mirror Integration Theory offers a roadmap to wholeness. It challenges the false separation between personal healing and societal change—proposing that the two must happen together, as a mirrored process.

By recognizing that individual and collective wounds are reflections of each other, we can design systems that heal rather than suppress, integrate rather than fragment, and restore rather than control.

The future of humanity depends on whether we choose repression or integration—whether we perpetuate cycles of suffering or embrace a path toward wholeness.

References

Porges, S. (1995). Polyvagal Theory and the Biology of Trust.

Schwartz, R. (1995). Internal Family Systems Model.

Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity.

Maté, G. (2018). In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction.

Snow, I. S. (2025). Mirror Integration Theory: A New Framework for Individual and Collective Healing.